1936: Macbeth With an All-Black Cast Plays Bridgeport

by Andy Piascik

For five days in the summer of 1936, Bridgeport’s Park Theatre played host to one of the most innovative and talked-about theater productions of that era: the Federal Theatre Project’s staging of Shakespeare’s Macbeth with an all-black cast, as directed by Orson Welles and produced by John Houseman. The play opened in New York City on April 14, 1936 at Harlem’s Lafayette Theatre, where it ran for ten weeks before moving to the Adelphi Theatre for two additional weeks. Advance word about the production had been so great that a reported 10,000 people gathered outside the Lafayette on opening night. Macbeth played to enthusiastic audiences, sold-out houses and mostly rave reviews during the twelve-week engagement that lasted through July 18th. (more…)

Between the Hills and the Sea

by Andy Piascik

Bert Gilden was born in Los Angeles in 1915 and moved to Bridgeport with his family when he was a young boy. He graduated from Central High School in 1932 and then from Brown University in 1936. (more…)

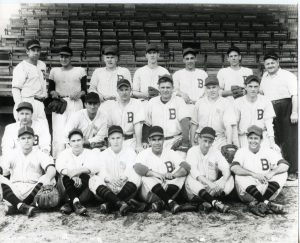

Bridgeport Baseball, 1947: Candlelite Stadium Opens and the Bees Return

By Andy Piascik

Bridgeport has a long, rich history of pro, semi-pro, African-American and minor league baseball. The city has played host to barnstorming major league teams, teams from the old Negro Leagues and to visiting minor leaguers who went on to achieve baseball immortality such as Lou Gehrig. Much of this history has been documented by local grassroots historians Michael Bielawa(1) and Mike Roer(2). (more…)

Bridgeport’s Original Little League

by Andy Piascik

Little League baseball was established in the United States in 1939 in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. From humble beginnings, Little League has expanded over the decades to many countries around the world involving tens of thousands of boys and girls aged 9 through 12 (girls were first officially allowed to play Little League in 1974).* The Little League World Series that began in 1947 and takes place every August in Williamsport is an incredibly popular event televised around much of the world, first in 1953 by CBS-TV and in recent decades internationally via ESPN.

Little League grew rapidly after the Second World War and the Bridgeport Little League was formed in 1948. In 1949, Bridgeport’s league officially affiliated with the central organization in Williamsport. That same year, 1949, marked the first year leagues from other countries were incorporated into the Little League structure.

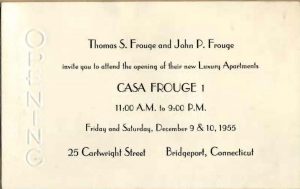

Casa Frouge, “Bridgeport’s First Luxury Apartment Building”

By Andy Piascik

When the 84-unit Casa Frouge high-rise on Cartright Street on Bridgeport’s West Side opened in 1955, its developer the Frouge Construction Company billed it as the city’s “first luxury apartment building” and “the outstanding apartment residence in New England.” Located across North Avenue from Mountain Grove Cemetery, the high rise is nine stories high with ten apartments on floors one through eight topped by four penthouse units. (1) (more…)

Congressional Red-Hunters Set Their Sights on Bridgeport

By Andy Piascik

In September 1956, the House Committee on Un-American Activities, commonly known as HUAC, came to Connecticut. The purpose was to hold hearings about activities of the Communist Party in New Haven and Bridgeport. HUAC had been formed in 1938 and was in its tenth year of actively investigating Communism. (more…)

Housatonic Community College: A Bridgeport Gem

By Andy Piascik

This Fall marks 50 years since the establishment of Housatonic Community College. The school has come a long way in that time, from facilities scattered throughout Stratford to an old industrial building on Bridgeport’s East Side to a lovely downtown campus. More importantly, enrollment has grown from 378 in the very first semester to almost 6,000 students and is likely to grow larger with new facilities and a continued commitment from the state of Connecticut.

Housatonic’s origins can be traced to the dramatic increase in the need for higher education in the early 1960s. The empire of the United States was at its apex and there was a great demand for a better-educated workforce to fill the many professional and technical jobs of an expanding economy. As the first of the baby boom generation reached college age, new universities were constructed, state college systems expanded and many community colleges were established.

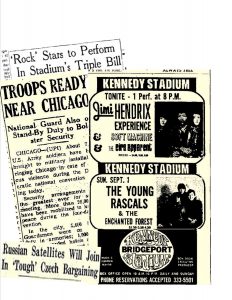

Kennedy Stadium Hosts the Jimi Hendrix Experience

By Andy Piascik

When Bridgeport’s Kennedy Stadium opened in 1964, there was as much excitement in the city as there was three decades later with the construction of the Ballpark at Harbor Yard and Webster Bank Arena. There were plenty of parks in the Park City at the time including many that were used by the Senior City League and other local athletic teams. But since the removal of the grandstand at Newfield Park, a long-time home to minor league baseball whose field was graced by Lou Gehrig among others, and the demise of Candlelite Stadium, which also hosted minor league baseball as well as semi-pro football teams, Bridgeport was without a similar venue until the construction of Kennedy. (more…)

Kiddo Davis

by Andy Piascik

One year when I was a teenager, I had a summer job pumping gas at a local gas station. Business at the station fluctuated and on one afternoon when it was quite slow, a distinguished looking man of about 70 pulled in. He got out of his car and we talked as I pumped his gas and checked under the hood. Or rather, he talked and I listened as he spoke at some length about baseball, specifically baseball in the days when he was a young man. Each time he saw me nod or smile in recognition at one of the famous names he threw out, he went on with a new story. Then he asked me if I knew anything about the New York Giants of the 1930s. I got the feeling he was testing me.

Ozzi’s Shoe Rebuilding, A Hollow Neighborhood Fixture for 69 Years

By Andy Piascik

In 1924, Nick Ozzi purchased a storefront building at 447-449 Coleman Street and established a shoe repair business, Ozzi’s Shoe Rebuilding, that lasted for 69 years. The business was located on the ground floor of a building that also included two apartments upstairs that served as a landing place for members of the Ozzi family as they moved from Italy to Bridgeport. (more…)

Pa’lante: The Young Lords in Bridgeport

by Andy Piascik

As Puerto Rico began to more acutely experience the economic ravages of colonialism in the years after the Second World War, more and more people from the island began migrating en el norte. Though most settled in the nation’s largest cities, Bridgeport was also a popular landing point. In fact, since the 1960’s, Puerto Ricans have made up a larger percentage of Bridgeport’s population than New York City’s. Statewide, Puerto Ricans have for many years been a larger percentage of Connecticut’s population than any other state and remain so today.

Solidarity Bridgeport Style

by Andy Piascik

On July1, 1979, 400 members of United Steelworkers Local 7201 employed at the Handy and Harman precious metals factory in Fairfield went on strike. There was nothing particularly unusual or exceptional about that; workers at factories in Bridgeport and the surrounding area regularly called strikes during the region’s industrial heyday. What was exceptional was the way in which a large number of people in Bridgeport responded when Handy and Harman employment representatives began actively recruiting replacement workers – scabs – in economically depressed areas of the city. (more…)

The Bridgeport Harbor Lighthouse

by Andy Piascik

The waters near Bridgeport were long served by lighthouses that helped to guide ships to their destinations. One that is still in use is the Penfield, which opened in 1874 and is located a mile from shore. A little more than a mile to the east is the Fayerweather, constructed in 1808 and long out of use though a popular part of Bridgeport history. (1) (more…)

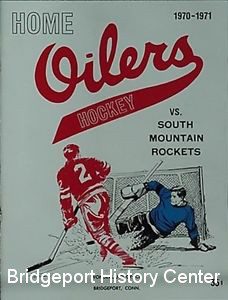

The Bridgeport Home Oilers

By Andy Piascik

Before there were the Sound Tigers, there were the Home Oilers. Before there was Webster Bank Arena, there was the Wonderland of Ice. The Wonderland of Ice is still there and now with two full skating rinks, but the Home Oilers are long gone. Long gone, yes, but not forgotten, both for the thrills they provided an admittedly small but devoted number of fans and for the small part they played in the explosion of interest in ice hockey in the city of Bridgeport, the state of Connecticut and, indeed, the United States. (more…)

The Bridgeport Sunday Herald and a Free Speech Fight

By Andy Piascik

Rarely has an American play met with the kind of government opposition that Clifford Odets’ Waiting for Lefty faced in 1935. Mayors and police departments forbade the staging of the play in a number of cities and stopped performances mid-play in others. Audience and cast members were arrested for protesting police actions. Locally, the Bridgeport Sunday Herald rallied to the cause of the play after it was banned in New Haven and thus played an important and honorable role in defending free speech.

Clifford Odets was 28 years old and a member of the left-wing, New York-based Group Theatre ensemble when he wrote Waiting for Lefty. (1) It was the first of his plays to be staged when it opened in a Group production at the Civic Repertory Theater on West 14th Street in Manhattan on January 5, 1935. (2) Among those in the cast were Odets, Elia Kazan and Lee J. Cobb. (3)

The Bronx Casket Company

by Andy Piascik

In 1933, Antonio Mastromonaco established the Bronx Casket Company on Webster Avenue in the Norwood section of the Bronx. Mastromonaco was born in Campobasso in Italy and emigrated to the United States around 1913. He had been a laborer in Italy and was employed for a while after arriving in the Bronx in the construction of the New York City subway system. His grandson Pete remembers hearing that Mastromonaco also had carpentry skills, skills he put to good use in the business he founded.

The Bronx Casket Company facility in the Bronx consisted of a shop where caskets were made, a showroom where they were displayed for prospective customers, and offices. The skilled casket makers were the heart of the business and they produced high-quality merchandise. Five of Mastromonaco’s sons worked for the company in various capacities. One Bronx local who was also an émigré from Italy and worked for the company for eight years was Salvatore Mineo, the father of movie star Sal Mineo. (1)

The Day Casco’s Workers Sat Down on the Job

by Andy Piascik

It was an event that lasted less than a day and involved only 50 people directly. It was organized, led and carried out by everyday workers and thus contradicted the mainstream narrative that only big people make history. Many of the participants were women so their actions were thus further dismissed, even ridiculed. Yet as the great historian Howard Zinn might have put it, mostly unknown and forgotten people occupied the Casco factory in Bridgeport in 1937 and struck a blow for themselves and workers in the city as a whole. (more…)

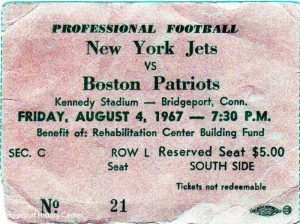

The Night Broadway Joe Brought His Act to Bridgeport

By Andy Piascik

There’s an old expression in Broadway theatrical circles that goes something like “Everything outside of New York is just Bridgeport.” Perhaps Broadway Joe Namath felt that way when he travelled to the Park City in 1967, perhaps not. But on one summer evening nearly 50 years ago, Bridgeport hosted an exhibition football game featuring the flamboyant Namath and the up-and-coming New York Jets. (more…)