Bridgeport’s Most Mysterious Millionaire Founder of A&P George Francis Gilman

By Carolyn Ivanoff

George Francis Gilman was a man recognizable to Bridgeporters, especially those in Black Rock. He was the wealthiest man in Fairfield County. When he retired from his legendary career as a tea importer to Bridgeport in 1878, he purchased a prominent 1762 colonial estate in Black Rock. Gilman was known for his expansive entertaining of famous celebrities, actresses, and the “upper crust” He and his wife were childless but had adopted a nephew. Mrs. Gilman passed away in 1891. After his wife’s death, Mr. Gilman no longer included the first families of Bridgeport in his entertaining, preferring to ignore them. He distanced himself from his adopted nephew, and he isolated himself thoroughly from local and familial relationships, but continued to host extravagant parties for actresses, artists, and the elite of the age. On November 7, 1894, after a lavish ball, the house went up in flames suddenly and spectacularly. Gilman, his guests, and his servants narrowly escaped, and several of New York’s privileged saved themselves by jumping from the windows in their night clothes or the expensive costumes they had worn to the ball. Gilman’s priceless art collection was destroyed, the entire home and contents lost. This extremely rich man replaced the stately old colonial home with a huge manner house. The mansion was placed well back from the road. Gilman insured that anyone walking the property could not see into his windows placing them well up. There were no doorbells or knockers on any of the entrances. The twenty room mansion had bathrooms placed between every other room. He built the house with day-labor which was expensive but provided the locals with good paying jobs. The end result was spectacular on the inside, but the outside was solid and non-descript.

Gilman loved horses. His stables were lavish and legendary, as were the various vehicles, especially his big Tally Ho coach and his many elaborate coupes. It was a common sight to see his head coachman Walter Lee conveying celebrities who were entertained by Mr. Gilman between the Bridgeport train station and the Black Rock mansion. Gilman minded his own business and expected others to do so as well. He was generous with his servants and employed sixty. He preferred immigrants whose English might not be the best. This protected his privacy. Many of them lived well and rent free on his property. When he traveled, he never closed the house keeping it ready at all times, and thus his servants were always employed. In the 1890s when unskilled labor might make slightly less than $10 a week, and a skilled laborer $15-$20 a week, Mr. Gilman paid his barber $2,000 a year to come to the house and shave him daily.

His cigar bill was $3,000 a year. He was sometimes called the “Coffee King” by Bridgeporters and he generously donated to many charities without fanfare or publicity. George Francis Gilman was a well-dressed, genteel man who garnered great curiosity in the community, but he took great pains to protect his privacy. After his death, his peculiar traits would be the stuff of headlines throughout the nation along with national speculation over who would inherit his millions.

George Francis Gilman was born in Waterville, Maine in 1826, son of a wealthy father, who was in the tanning business. In the 1850s George worked in the leather trade for his father in New York City. By 1858, George had his own warehouse. His father died in 1859 without a will and George and his battling brothers fought bitterly over their father’s estate for the next thirty years. The year of his father’s death, George decided to enter the more respectable tea business and left his tanning business interests to a brother to manage. Gilman & Company began as a tea and coffee wholesaler. The company did well until 1862 when Congress imposed import duties on tea and coffee to help pay for the Civil War. The coffee market then collapsed when the government became the primary purchaser to supply the army. That year, Gilman renamed the company, “The Great American Tea Company” and diversified his products to tea, coffee, baking powder, spices and expanded into retail. Quickly, Gilman opened five stores and moved his office and warehouse to 51 Vesey Street in New York City.

George Gilman was a marketing genius, referred to as the P.T. Barnum of tea and coffee, a comparison many Bridgeporters who knew, or had known Barnum, could relate to. Gilman pioneered many of the retail advertising concepts that are still used today. At first his business profited greatly by buying tea, coffee, spices, etc., in large volume, cutting out the middleman, and selling to customers at less than the prevailing prices. Gilman’s employee, George Hartford, at first his bookkeeper, and then his partner, ran the company as Gilman developed new marketing strategies. Gillman was a master of “visual” advertising. Advertisements were run in church publications and rural newspapers. For teetotalers who frowned on the use of liquor and were major customers, large red Ts marked the front of his stores. White horses pulled his products through the streets in flashy red wagons. Self-appointed “Agents” were recruited to create clubs that placed combined group orders at a discount and then distributed orders to purchasers. Agents, club leaders, and customers received premiums, coupons that could be collected and redeemed for plates, pottery, pictures, prints and other featured giveaway items. With its stores, retail sales, and mail order businesses the company was wildly profitable. By the end of the Civil War the company was expanding. In 1869, Gilman changed his company name again to The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, in honor of the completion of the transcontinental railroad, which he would use to launch stores into the mid-west. In 1876 the company reached the 100 store mark and successfully created the first chain store in the United States, three years before F. W. Woolworth opened his first successful “Woolworth’s Great Five Cent Store.”

In 1871, the great Chicago fire devastated the city and left 100,000 people homeless. Gilman and Hartford saw opportunity in sending relief supplies to the city, and they also sent employees to help distribute them. After assisting with recovery from the fire, Chicago became home to the company’s flagship store. Store fronts were exotic and eye catching, painted red and gold, with the large red T hanging in the front, illuminated with gas lights. Saturdays meant in-store customers might be treated to the music of live bands. The sumptuous store inte riors Gilman designed were Chinese inspired, with paneled and gilt walls, cockatoos greeted customers who cashed out their purchases at a pagoda-shaped golden sales desk. Despite its elaborate stores, the company’s great success was due to its appeal to cost conscious customers. The company pioneered the “club plan” discounts, bulk mail order sales, coupon and premium giveaways, private labels and house brands, inexpensive tea and coffee blends. In 1882 it introduced Eight O’clock Breakfast Coffee which remained A&P’s trademark brand through the 20th century.

riors Gilman designed were Chinese inspired, with paneled and gilt walls, cockatoos greeted customers who cashed out their purchases at a pagoda-shaped golden sales desk. Despite its elaborate stores, the company’s great success was due to its appeal to cost conscious customers. The company pioneered the “club plan” discounts, bulk mail order sales, coupon and premium giveaways, private labels and house brands, inexpensive tea and coffee blends. In 1882 it introduced Eight O’clock Breakfast Coffee which remained A&P’s trademark brand through the 20th century.

In 1878, George Francis Gilman retired to his home in Bridgeport to live in luxury. George Hartford continued to conduct the day to day business of the company, but Gilman remained closely connected and kept his finger on the pulse of his empire. He may have been one of the first CEOs to work remotely. Until just a few days before his death, he continued to receive daily reports from each of his 290 stores by telegraph at his Black Rock mansion. He knew how much each one of his stores made or lost each day. Each of his 290 stores was required to send him $1 a day in cash. He viewed 290 as his lucky number. He began his tea business at 290 Spring Street in New York City. His post office box was 290, and the address of his Bridgeport store was 290 Main Street. He insisted his stores nationwide not number more than 290. If a new store opened, one would have to close. 290 was his magic number.

During his retirement, Gilman continued to entertain on an excessive and luxurious scale. He continued to collect great art. When his barber’s daughter proved to have artistic talent, he paid for her education and sent her to Europe to study. He surrounded himself with young people. He entertained celebrities, young actresses, Yale students, and the nation’s elite at his Black Rock manor on an opulent manner. His eccentricities became more and more pronounced. No clocks were allowed to remind him of the passing of time, no mirrors, no telephones, he detested photographs of himself. If anyone was ill near him, they were banished from the house. He wanted nothing to remind him of death. He would not ride on a train transporting body. If a funeral procession or hearse passed near him, his coachman was ordered to drive away from it. His house was always full of people, but he kept himself apart from his guests and servants. He had a great fear of assassination at the hands of his relatives. During the family war over his father’s estate, after his father died without a will, he was confronted by his angry brothers on a New York City street and he never forgot it. He hated and feared his brothers, half-siblings, and relatives, and he was excessively paranoid and secretive about the true amount of his own vast wealth.

On March 3, 1901, George Francis Gilman died of an attack of Bright’s disease in his Black Rock mansion. Immediately his surviving siblings, half siblings, and others made claims upon his estate. The headlines in the Bridgeport and national papers asked, “Did Gilman Leave a Will?” Soon, the headlines blared “No Will Found.” Speculation about the amount of his estate varied between $40 and $70 million; no one knew for sure. Relatives from as far away as the Philippines appeared to claim their share. They were opposed by several of Gilman’s siblings and half-siblings. An actress, Mrs. Helen Blakeley Hall claimed to be his adopted daughter. The barber’s daughter Gilman had educated made her own claims. After years of managing the stores and business, George Hartford had nothing on paper to prove his claim that he was Gilman’s partner. The states of Connecticut and New York both fought for the right to probate the estate because they both wanted the inheritance taxes that would result from the proceedings. All of this played out in lurid national headlines. Gilman’s eccentricities were dragged out and explored. The personal lives of the claimants, especially the actress’s claims, and divorce, were published in a soap opera-like saga in the nation’s newspapers. Finally, in 1903 all claims except Mrs. Hall’s were settled, but appeals went on. George H. Hartford was awarded all of the common stock and a large percentage of the preferred stock, giving him control of the company. He was able to purchase the remaining preferred stock from Gilman relatives. Under the leadership of Hartford and his sons, A&P, the company George Francis Gilman founded, would become one of the iconic grocery chains of the 20th century.

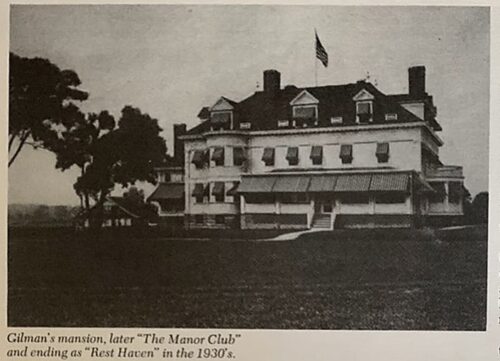

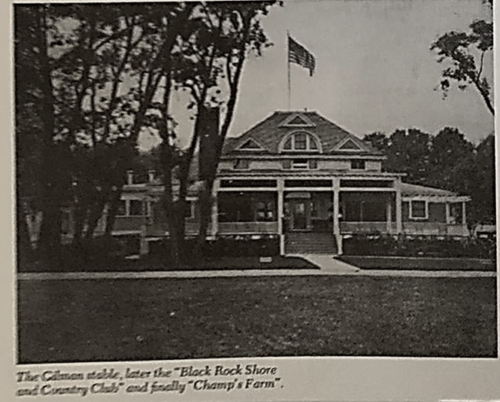

In 1915, Simon Lake, Bridgeport business magnate and inventor of several submarine types, bought Gilman’s Black Rock property. He wanted to subdivide and convert Gilman’s mansion into a hotel. When city ordnances prevented this, Lake turned it into a residential businessmen’s club named “The Manor Club.” In 1917 the extensively renovated manor house and stable buildings were a temperance social club, with a restaurant, and a recreation park on the grounds, including a dining room with orchestra alcove, a skating rink, a saltwater swimming pool, tennis courts, bowling alley, billiard room, and dancefloor. This enterprise failed in 1921 and in 1925, Simon Lake’s relative B. F. Champion created the Champs Farm Recreation Park. By 1934 the manor house had become a rest home, “Rest Haven” and the recreation building housed a skating rink. On November 22, 1936, the Bridgeport Sunday Post ran an article, “The House that Premiums Built Will Fall” Magnate Gilman’s Mansion at Black Rock to Come Down; the article called it a “Unique Pile.” In 1937 both buildings were razed, and the land was subdivided into building lots.

Above left: Gilman’s mansion, later “The Manor Club” and ending as “Rest Haven in the 1930s;

Above: The Gilman stable, later the “Black Rock Shore and Country Club” and “Champ’s Farm.” (Bridgeport History Center)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bridgeport History Center Archives: including the George Francis Gilman files and newspaper collections: The Bridgeport Farmer, The Bridgeport Herald, The Bridgeport Evening Post, The Sunday Bridgeport Post.

Anderson, Avis, H., A&P The Story of the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, Arcadia Publishing, Charleston, South Carolina, 2002.

Black Rock: A Bicentennial Picture Book—A Visual History of the Old Seaport of Bridgeport, Connecticut, 1644 to 1976, Fairfield Graphics, Inc. 1976.

Civil War Talk (Blog) The Great American Tea Company,

https://civilwartalk.com/threads/the-great-american-tea-company.178300/

Justinius, Ivan, O., History of Black Rock, 1644-1955, Black Rock Civic and Business Men’s Club, Antoniak Print Service, Bridgeport Conn., 1955. https://archive.org/details/historyofblackro00just/page/55/mode/1up

Ukers, William, H. All About Tea, Vol. II, The Tea and Coffee Trade Journal Company, New York, New York, 1935,

Library of Congress, Chronicling America, America’s historic newspaper pages from 1777-1963,

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/

Newspapers.com