Dr. Allen C. Bradley

REMEMBERING BRIDGEPORT PHYSICIAN ALLEN C. BRADLEY, 1875-1945

On February 1, 2024, I attended a program at the New Haven Museum celebrating Black History Month and the tenth anniversary of a book that I had contributed to, African American Connecticut Explored. The book is a compilation and celebration of what the preface stated was, “A book for a general audience that surveys the long arc of the African American experience in Connecticut.” One of the panel speakers urged the audience to remember and recover the stories of our history.

During the program my thoughts turned to the stories my parents told of Dr. Allen C. Bradley. The black Bridgeport physician who was their doctor. He was always spoken of fondly by my parents and elderly relatives who lived on Bridgeport’s East Side during the Great Depression. For many years this dedicated doctor served the immigrant and black populations of the City of Bridgeport. He is all but forgotten now. I remember him because my parents remembered him and told me his story. I have a fondness for the stories of Bridgeport, the city of my birth. I have one cousin left who has vague memories of Dr. Bradley, making house calls. That would have been in the early 1940s before the doctor passed away. My cousin remembers a small man, with a big fur coat and large brimmed hat. Both my parents remembered Dr. Bradley making house calls to their homes. Many of the immigrant families Dr. Bradley served spoke little or no English. Because many of these immigrants, including my grandparents, often had no money Dr. Bradley would try to prescribe home remedies whenever possible. One of the remedies my father remembered Doc Bradley prescribing was salt water soaks for rashes, and if it was summer, would advise parents to take that baby with the bad diaper rash to Pleasure Beach and soak up the fresh air, sun, and salt water and let the kids enjoy park. Vinegar and olive oil were prescribed for topical remedies. Cod Liver oil was a prophylactic during cold and flu season. My mother never lost her belief in the benefits of cod liver oil and would dose us with a daily tablespoon in the 1960s, much to my disgust. Of course, for my parents as children, there was always that dreaded castor oil that was good for whatever ailed you. My mother at least spared us that.

My 98 year-old uncle Joe recently wrote down his childhood memories for the family which he titled, Once Upon a Time: A Life of Memories, of growing up in Bridgeport. He included a memory of Dr. Bradley from his childhood in the late 1920s and 1930s. He couldn’t remember the doctor’s name, but when I read what my uncle wrote I knew it was Dr. Bradley because of my parents’ stories. My uncle was so thrilled when I said, “Uncle Joe, that was Dr. Bradley.” In his book of memories, my uncle wrote:

Now this story is about a doctor who took care of us in the neighborhood. He would come to the corner of Boston Post Road and Farmer Avenue and blow his horn. The kids would come running and, in the summer, he would give us candy, and in the winter, we would hook up our sleds to his bumper and he would pull us around the neighborhood. If we needed help, we would stand in front of the house and we would wave to him because we had no telephone. The first thing he would do was line us up in the house and look at our mouths. At that time, we all had measles and mumps. If somebody else had measles in the neighborhood, we would go to their house to catch the measles. He would check my father’s heart and look at his face. If his face was red, he would assume he had high blood pressure. He would tell my father to take one leach a week. Everyone had a leach in a jar in their kitchen. When I worked in the drug store, I used to put the leeches in the bottles. Everyone had arthritis (Note: it was believed that sitting in the sun cured arthritis) so they would sit in the sun and on the walking trail, you would see people bathing in the sun. He (Dr. Bradley) would never ask for money, but my mother would give him what she had and a loaf of bread. By the way, the doctor was black.

Now my uncle’s written memory is through the eyes of a child, but my parents also remembered that Dr. Bradley never asked for money. Their parents had nothing to give him anyway. But if you needed a doctor, Doc Bradley would come to your house. Times were difficult. My father told me that they often went hungry. My uncle’s parents had twelve surviving children when they lost the family home during the Great Depression. It was a devastating blow. My uncle was a little boy and was so confused when he heard his mother say that they were losing the house. He asked his brother, “Where did a house go when it got lost?”

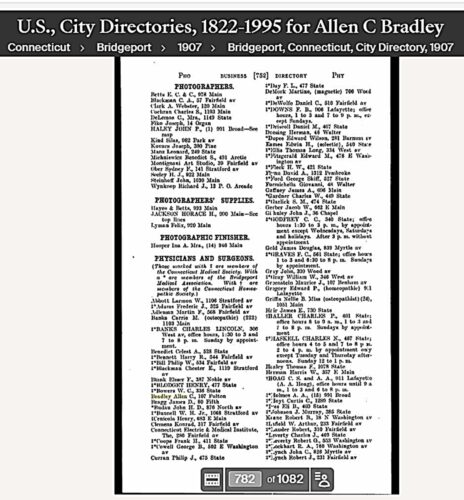

Dr. Allen Christopher Bradley was born on November 29, 1876, in Beaufort, South Carolina. But perhaps the year was 1879, or as his tombstone states in Mountain Grove Cemetery, 1875. There are no records to be found of his early life or birth in Beaufort, South Carolina. Perhaps because he was born directly after Reconstruction ended it might be logical to assume he was the son of formerly enslaved parents. In 1903 he is listed in the New York Marriage Index on April 29, 1903, as marrying in Kings, NY, Miss Bertha Carroway, born in North Carolina. In 1904 Dr. Bradley is listed in the Bridgeport City Directory as practicing medicine and renting at 61 Elm Street. Dr. Bradley is listed in every subsequent Bridgeport City Directory as a practicing physician for the next forty years.

I had always hoped to find a photograph of Dr. Bradley or even more people who remembered him. I haven’t been successful. I guess it’s too long ago. We have physical descriptions of him from official records, and of course, the memories of the large hat and fur coat he often wore when making house calls. In 1917, according to the mandated draft registration card completed by every male over 16 years old in the State of Connecticut before World War I, Dr. Bradley was living and practicing medicine at 55 Highland Avenue, his own home, where he lived until his death in 1945. His draft registration paperwork lists his age as 33, his height as 5’2” and his weight at 134 lbs. In 1942, during the Second World War, when he again officially registered with the draft board for the State of Connecticut, his weight was down to 125 lbs.

I had always hoped to find a photograph of Dr. Bradley or even more people who remembered him. I haven’t been successful. I guess it’s too long ago. We have physical descriptions of him from official records, and of course, the memories of the large hat and fur coat he often wore when making house calls. In 1917, according to the mandated draft registration card completed by every male over 16 years old in the State of Connecticut before World War I, Dr. Bradley was living and practicing medicine at 55 Highland Avenue, his own home, where he lived until his death in 1945. His draft registration paperwork lists his age as 33, his height as 5’2” and his weight at 134 lbs. In 1942, during the Second World War, when he again officially registered with the draft board for the State of Connecticut, his weight was down to 125 lbs.

In the 1907 Bridgeport Business Directory under the heading of Physicians and Surgeons, there were categories for doctors who were members of the Connecticut Medical Society, the Bridgeport Medical Association, and the Connecticut Homeopathic Society. There was also a listing for the Connecticut Electric & Medical Institute. Like many of the doctors listed, Dr. Bradley was not affiliated with any of these organizations.

The 1910 census shows Dr. Bradley renting a house on Fulton Street, but sometime before the 1920 census, Doctor purchased a house at 55 Highland Avenue where he lived until his death. The 1920 census showed the Bradley’s had a live in maid as well as a boarder. The couple never had children of their own but census records from 1920 and 1930 showed a niece and two nephews lived with the couple.

By the 1940 census, Dr. and Mrs. Bradley owned their home at 55 Highland Avenue, which was valued at $6000. The doctor’s income was $2000 per year and in 1939 he worked 52 weeks, 60 hours per week. The 1940 census also asked questions about education and of the head of household had attended school. Dr. Bradley responded yes. The census also asked what the highest grade completed was. Dr Bradley attended elementary school until the 5th grade.

Dr. Bradley practiced medicine in Bridgeport for over 40 years. He was well respected and trusted. Like many doctors in the United States during the 19th century and early 20th century, his education probably consisted of an apprenticeship to an experienced doctor. In fact, many American doctors were not formally educated in colleges. During the 19th century before the Civil War formal medical education from well-known medical schools was a two year curriculum, with the second year being a duplicate of the first. It was not until after the Civil War that formal medical education became more common. After the Civil War, medical societies began to form and licensing requirements for medical professionals became more prevalent. Still early in the 20th century many practicing American doctors achieved their profession the old way, through apprenticeship and practice. With the lack of available records, we can assume this was the case for Dr. Bradley.

Dr. Bradley probably came to Bridgeport in 1904, the earliest listing for his practice in the city directory. He had married in 1903 in New York, and he practiced medicine in Bridgeport for over forty years until his death in 1945. The newspapers of the time were a social and political lifeline for Americans everywhere. Dr. and Mrs. Bradley’s social engagements were often reported in the local Bridgeport papers when they attended functions or when they hosted out of state guests in their home. Dr. Bradley was active in Bridgeport politics. In 1912 he was the President of Bridgeport’s Colored Republican Club and the Bridgeport Evening Farmer reported that the city’s black Republicans’ unanimously endorsed Taft for president. Apparently, Theodore Roosevelt, running for president under the Bull Moose ticket, had spoken what the group believed were distasteful comments about “race suicide” also reported in the Farmer. The title of the Farmer’s article reads, “Negros Denounce Moose.”

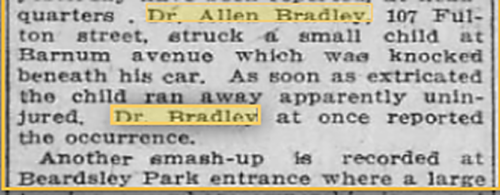

Dr. Bradley had some of his cases reported in the Bridgeport papers. Often when he reported abuse and neglect to the authorities. In one instance he reported himself when he struck a small child with his car on Barnum Avenue. The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer, Aug 25, 1913, reported that as soon as the child was pulled from beneath the car the child ran away seemingly unhurt. Dr. Bradley immediately reported the incident.

Dr. Bradley had some of his cases reported in the Bridgeport papers. Often when he reported abuse and neglect to the authorities. In one instance he reported himself when he struck a small child with his car on Barnum Avenue. The Bridgeport Times and Evening Farmer, Aug 25, 1913, reported that as soon as the child was pulled from beneath the car the child ran away seemingly unhurt. Dr. Bradley immediately reported the incident.

One of Dr. Bradley’s cases became a sensational tragedy in Bridgeport that received coverage for months. In mid-January 1910 he was called to the home of a 17 year-old girl by her parents. He was the family doctor and upon examining her, immediately reported the case to the authorities and had her moved to the hospital. The girl was in serious condition from an illegal abortion performed by a well-known white doctor in the city. Both the doctor and a young black coachman were arrested. The young coachman frequently chauffeured doctors on various calls. The young man admitted to police he was responsible for the girl’s condition. Several news articles alluded to the family’s poverty. The girl lingered for weeks at Bridgeport hospital. Finally, in May she asked to go home to die and passed away on May 17, 1910, from the effects of the botched surgery. Lawyers for the defendants and the prosecutor claimed that the police did not get statements from the girl that were admissible in court. After months of delays and legal maneuvering, on August 18, 1910, the Evening Farmer reported the case against the doctor and coachman was nolled.

On June 28, 1927, the Bridgeport Telegram reported that with the approach of the 4th of July injuries from guns were on the rise and five children were injured. Dr. Bradley was called to attend to one of the injured children, a child who was shot in the hand by a playmate.

There is sometimes power and permanency in words and I wanted to write down these stories that my parents told me about Dr. Bradley. This man was a beloved physician who deserves to be remembered and honored. A man who spent his life in Bridgeport, Connecticut dedicated to serving his patients no matter who they were: black, white, immigrants, poor. This article is dedicated to his memory. He passed in 1945 and that’s so long ago for many of us. The generation of the Great Depression and the Second World War is melting away into the past beyond living memory. Words in stories told, and words written down have the power to keep history alive. Dr. Bradley was a quiet Bridgeport hero. He did so much good, for so many people in Bridgeport, for so many years. He deserves to have his story written down and remembered. This article is written to honor this dedicated Bridgeport physician whose life touched so many lives for the better, including my parents, grandparents, and family. May the memory of this good man transcend the boundaries of time.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bollett, Alfred, Jay, Civil War Medicine: Challenges and Triumphs, Galen Press, 2002

Bridgeport City Directories

Bridgeport Telegram

Bridgeport Evening Farmer

Bridgeport Times

Mencel, Joseph, Once Upon a Time: A Life of Memories

State of Connecticut Draft Registration Records

US Census Records