The Day Casco’s Workers Sat Down on the Job

by Andy Piascik

It was an event that lasted less than a day and involved only 50 people directly. It was organized, led and carried out by everyday workers and thus contradicted the mainstream narrative that only big people make history. Many of the participants were women so their actions were thus further dismissed, even ridiculed. Yet as the great historian Howard Zinn might have put it, mostly unknown and forgotten people occupied the Casco factory in Bridgeport in 1937 and struck a blow for themselves and workers in the city as a whole.

In the long history of class conflict in the United States, the decade of the 1930’s was a particularly contentious period. In Bridgeport, as in virtually every other part of the country, workers fought back against plant closures, unemployment and poverty as well as for democratization of the workplace. And as the Park City was one of the nation’s great industrial hubs, it was only natural that the sit-down strike was one of many tactics Bridgeport workers utilized.

The sit-down strike is a tactic used most effectively by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) three decades before the action at Casco. The idea of a sit-down is to stop production by occupying the workplace, rather than by withdrawing from it, as leaving the workplace and striking from the outside leaves open the possibility of employers bringing in replacements (scabs). The sit-down was revived to great fanfare and with remarkable success when autoworkers began a long occupation of General Motors plants in Cleveland and Flint on December 30, 1936.

Set on Bridgeport’s West End next to the railroad tracks, Casco (Connecticut Automotive Specialty Company) opened in 1924. Workers there made products for cars including pop-out cigarette lighters that were then a relatively new feature on many automobile dashboards. Tensions between workers and management had been escalating for some time prior to the sit-down strike. Management was actively soliciting workers to join its company union, the Casco Employees Association (CEA), while at least several hundred workers had signed cards with the United Electrical, Radio and Machine Workers of America (UE), one of the rapidly growing affiliates of the newly-formed Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO). Alarmed at the growth in the plant of the UE, and in an apparent attempt to cripple the workers’ organizing efforts, Casco President Joseph Cohen issued an order the morning of April 6, 1937 that the plant would temporarily close at noon that day for inventory.

Caught off guard, 850 of the 900 workers left at noon including many who undoubtedly would have remained had they known that 50 of their co-workers had decided to occupy the plant. The 50 sit-down strikers announced that they intended to remain until a set of demands that included management recognition of the UE as their bargaining representative were met. Supportive workers who had left formed picket lines outside the plant on Railroad and Hancock Avenues, sent word of the action to the families of those inside and contacted organizers from the UE.

Cohen and other company officials responded by declaring that the factory was closed and would not reopen until their demands were met. They also announced hundreds of layoffs. While refusing to accept that reductions were necessary, the workers and the UE immediately countered with a plan to prevent any layoffs by temporarily reducing the hours of all. Cohen unconditionally rejected the proposal, saying, as quoted in a story in the Bridgeport Post, “Positively no. I’ll run my own plant.”

Cohen’s words cut to the heart of what was at stake. At Casco, as elsewhere, the sit-down strike was a direct challenge to management’s control of production. A plant occupation starkly poses the question, a question workers in many places in 1937 had begun to seriously consider, of whether owners and managers are necessary or even desirable. Cohen’s unease was the unease that haunts all business owners, whether of small-ish operations like Casco or of the massive empire of General Motors: that through collective action, and especially workplace occupations, workers would come to envision and, more importantly, act on constructing a society without bosses.

Meetings of the parties carried into the evening. On Railroad Avenue, meanwhile, Casco workers and others continued picketing in support of the strike. In anticipation of a potentially lengthy standoff, they also tied mattresses and food to ropes that the occupiers pulled up through open windows. A photographer from the Bridgeport Post and Bridgeport Telegram was allowed inside and took two photos that appeared in both papers the following day.

Early on the morning of April 7th, an agreement was reached. A significant wage increase would be implemented and management agreed to recognize the UE (soon to be a major force in Bridgeport as the representative of workers at GE, Westinghouse/Bryant Electric and many other city shops). All talk of layoffs ceased, the occupiers would not be disciplined and the plant would remain closed while management took stock and made way for new production lines. On virtually every count, it was a resounding victory for the workers.

As in Flint and many other instances, the Casco workers utilized collective action to make significant gains. That should be celebrated all these years later as much as the Casco workers themselves undoubtedly celebrated in the days after the occupation. Still, there are also nagging questions that began to present themselves in 1937 that plague workers to this day.

Wittingly or not, for example, organizers from even radical unions like the UE helped pull workers away from the very awareness and possible action owners like Cohen feared. The objectives of the UE and the CIO as a whole were state-sanctioned exclusive representation as embodied in the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), class peace and collective bargaining agreements predicated on the corporation’s right to rule. Strikers taking over plants was fine as a temporary tactic but long term, labor’s vision and its relationship with workers was ultimately not so different from that of the business class, as became more apparent over time. Not long after the Casco strike, for example, the UE and other CIO unions began to sign off on contracts that virtually without exception forbade work stoppages that they did not authorize. Also included in the standard contract was a management prerogative clause that ceded all decisions about production, including the right to permanently close the plant, to the company.

That does not diminish what the Casco workers accomplished in 1937. On the contrary, it is in their spirit that we struggle for a way out of a framework that workers today are trapped in.

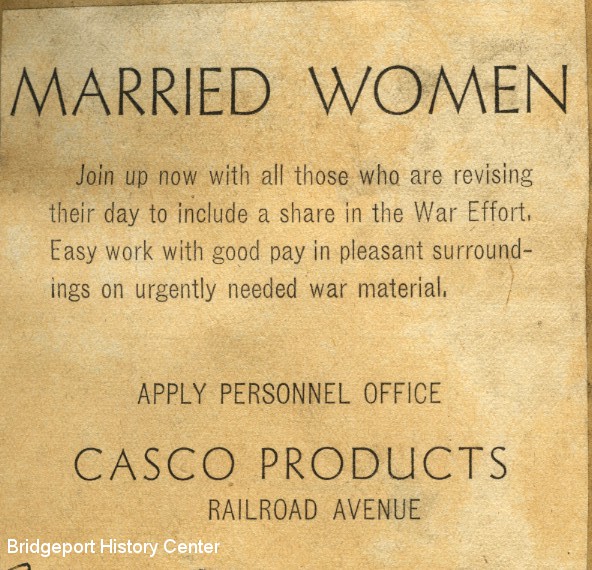

Local newspaper notice from the early 1940’s