Death and the Historian

by Elizabeth Boyce

Just a few years back, my youngest daughter innocently summed up my work to new friends saying: “Oh, and that’s my mom.” As they passed by, she added, “She works with dead people.”

She wasn’t wrong. I do spend an inordinate amount of time getting to know the people of the past. So, for this Halloween, let me share with you the intertwining stories of two men who, like me, were historians. They each spent many hours walking amongst the headstones of local cemeteries-including those right here in our town. And while that might seem like a morbid pastime, these men were pioneers in local historic appreciation and preservation.

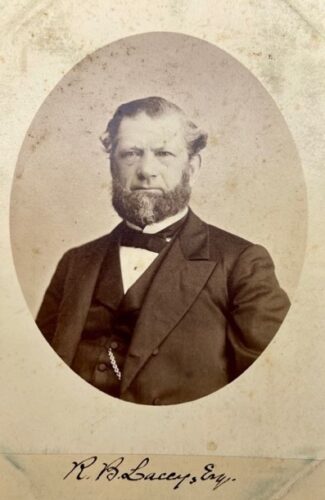

Rowland Bradley Lacey, portrait photograph, carte-de-visite. Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public

This tale begins with an Easton boy making it big in the city of Bridgeport. Born in 1818, Rowland Bradley Lacey came from a family that traced their lineage to the first settlers of North Fairfield parish with his ancestor, Edward Lacey in 1755. Rowland grew up the only son of Jesse and Edna Lacey and lived on the family farm just off present-day Sport Hill Road along with his paternal grandfather, Zachariah. He spent his early years in the company of this elderly veteran who served in the War of Independence. The young man listened and wrote down all the accounts of battles, close calls, and cold winters during the revolution.Perhaps it was those old stories that inspired his love of history. He excelled as a student at the local Staples Academy, and by the age of sixteen he was employed as a schoolteacher. By eighteen he had moved to Bridgeport and was working various jobs at the post office, the fire department and even the railroad. Eventually he landed a position in a saddle making company and his diligent work at Harral & Calhoun led to him managing the factory and then owning the business by 1863.

As head of the renamed Lacey, Meeker & Co., Rowland was a respected and wealthy man. Not only was he a pillar of success in the business community, but he was also actively involved in much of the early civic planning for Bridgeport. He worked to improve the city’s educational department, public works, and the chamber of commerce. Regarded as a man of extraordinary moral character, he was described as a “total abstainer” from any intoxicants. In addition to all his business and civic volunteer work, he was also senior deacon at Bridgeport’s First Congregational Church.

For his pleasure and hobby, Rowland was known for his love of local history, and he had a keen eye for preserving artifacts. He encouraged seniors to record their heritage, dust off the old books in their attics and tell their family stories for posterity. Rowland was also particularly fond of the old cemeteries and appreciated the valuable inscriptions preserved on their stones.

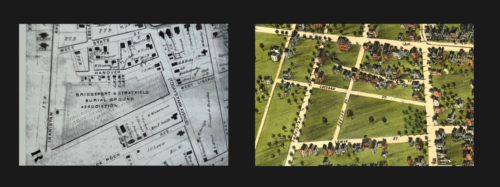

The Old Stratford and Bridgeport Burial Ground as rendered on a map from 1867 and then in 1875. Notice the area between Park Avenue and Iranistan Avenue no longer indicates the cemetery. Map detail on left, Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library and detail on right, Library of Congress.

During the post-Civil War period however, cemeteries were a bit of a sore subject in Bridgeport. While the city could cheer for its grand new buildings and open spaces earning it the “Park City” moniker, this same development contributed to the destruction of historic landmarks, particularly the old cemetery off what was once Division Street, now Park Avenue. Closed by state statute in 1873 after P. T. Barnum’s stint as a legislator in Hartford, the cemetery association was deemed financially destitute, and its dissolution resulted in the relocation of thousands of bodies, mostly to the newly constructed Mountain Grove Cemetery.

The fact that Barnum had a fiscal interest in the new cemetery and benefited financially from the sale of new homes built on the old burial site was not lost on contemporaries. While we cannot put too much confidence in anonymous accounts published years later describing a gruesome transfer of bodies with rotting coffins and bones scattering along the city streets, we do know the closure was deeply upsetting to the descendants of those exhumed. There is also undeniable evidence that many of the old headstones were broken, lost and repurposed for walkways. This sacrilege would haunt Barnum in his mayoral candidacy in 1875.

Inspired by these losses, a group of antiquarians, genealogists, and citizens interested in local history began planning a formal organization to promote the awareness of these subjects and raise public interest. The first official meeting of the Fairfield County Historical Society occurred on February 4th, 1881, and Rowland Lacey was elected chairman and later president. (This should not be confused with the Fairfield Historical Society that was established in 1903.)

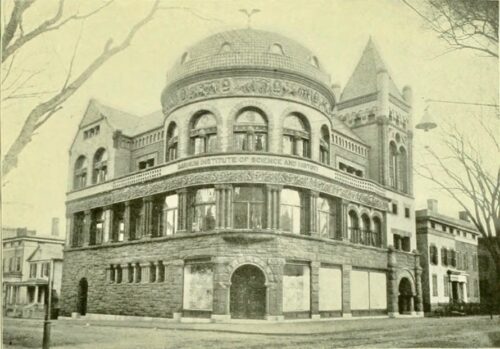

Not long after its founding, the Society’s meetings and publications attracted the attention and support of distinguished citizens with both philanthropic and academic interests. Ironically, P.T. Barnum became a member after writing to Rowland letting him know he had asked George C. Waldo, the prominent editor of the Bridgeport Standard, to propose him for membership. Barnum’s interest in the Historical Society may have been twofold. On the one hand we know through his letters that he seemed genuinely interested in learning more about his family’s heritage and on the other, it is likely that he saw the Society as a means to further elevate his standing and repair any ill perceptions of his land dealings. He soon became one of the organization’s greatest benefactors, providing a newly constructed building to house them and an initial endowment to fund operations. Completed in 1893, the Barnum Institute of Science and History still stands today and continues to house some of the Society’s collections.

The Barnum Institute of Science and History as it appeared circa 1897 on the corner of Main and Gilbert Streets in Bridgeport. The first floors housed the Bridgeport Scientific Society while the second was for the Fairfield County Historical Society. The third floor had an auditorium used for lectures by both organizations. The grand opening ceremony was on February 18, 1893.

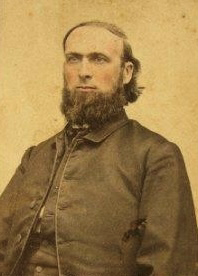

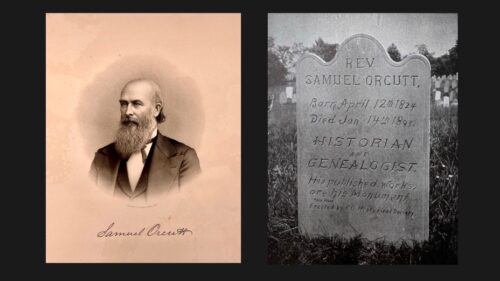

One of the influential citizens that Rowland Lacey befriended at this time was the historian, Samuel Orcutt. Originally from Berne County in Albany, New York, he was, like Rowland, the grandson of a Revolutionary War veteran. Samuel was also keenly interested in history and began employment as a schoolteacher. Continuing his education at both a seminary and a theological college, he began a lengthy career in preaching. Ordained as a minister in 1851, he traveled between parishes in New York until 1872 when he accepted a position in Connecticut. It was here that he began to research and compile town histories. He published his work on Wolcott in 1874 and that was followed with studies on Torrington, New Preston, Derby, and New Milford.

Reverend Samuel Orcutt in an undated family photograph.

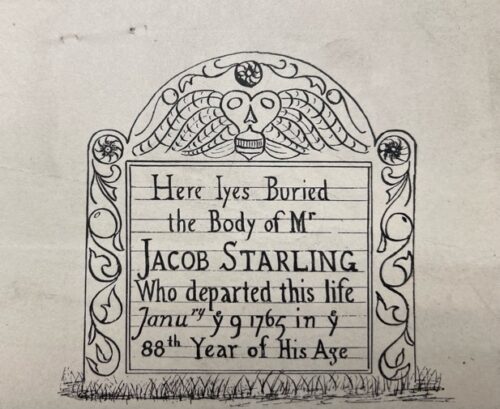

Samuel Orcutt spent long hours in the local graveyards drawing headstones and copying inscriptions. Here is a particularly well-done pen and ink drawing of Jacob Starling’s stone in the old Stratfield Burying Place (Pequonnock Cemetery) in Bridgeport. Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library.In these volumes, he recorded stories from local elders, composed genealogies from archives, took careful notes and copied inscriptions from graveyards. By the time he arrived in Bridgeport in 1884, he had earned a reputation as a distinguished scholar. His methodology in compiling data from primary sources and his interest in documenting cemeteries appealed to Rowland and his associates.

Samuel Orcutt spent long hours in the local graveyards drawing headstones and copying inscriptions. Here is a particularly well-done pen and ink drawing of Jacob Starling’s stone in the old Stratfield Burying Place (Pequonnock Cemetery) in Bridgeport. Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library

Encouraged by the Society’s willingness to help and their financial support, Samuel compiled A History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport, Connecticut. Published in 1886, this book still stands today as an important work on the city and its environs. However, it was not a financially successful project, and this failure disheartened the author.

His disappointment combined with recurring bouts of malaria, set him on a journey out west to California. Visiting his eldest son, he hoped the climate would improve his health and the region would offer an opportunity to explore new areas for preaching. He returned to Connecticut in the Spring of 1892 after learning of his youngest son’s sudden death. Herbert Crosby Orcutt died at the age of 23. Described as a promising young man, he developed a carbuncle on his lip that was lanced. His death was caused by infection and highlights the high mortality rate for ailments that can be treated today with antibiotics.

Samuel was devastated. Rowland wrote that sorrow fell upon his friend with a “crushing weight, and he never ceased to mourn” his son’s premature death. Letters preserved in the archives of the Society record that sadness pervaded Samuel’s writing at this time. His grief was amplified by the additional loss of “so many old friends that have gone out of this life” such that he was “almost heartbroken.” He wrote to one colleague, “I do not see how you and others have lived through such woes.”

His friend Rowland knew all too well the pain of losing a child. He had buried two of his own young sons: Edward was six years old when he died in 1852 and his second son, Henry was a year old when he died in 1855. Adding to this grief, Rowland’s first wife, Jane Eleanor Sherman, passed away after giving birth to their fourth child in 1857.

Jane Eleanor Sherman Lacey and her son Edward, family archives. From B. Scott Crawford’s study, Dating Jane: Domesticity, Death, and Photography in a 19th Century Portrait

At the time of their deaths, Rowland was in the prime of his business years and was left with a young daughter and an infant son to raise. And while we know he remarried and continued a busy schedule, there is evidence that he had felt his loss as profoundly as Samuel.

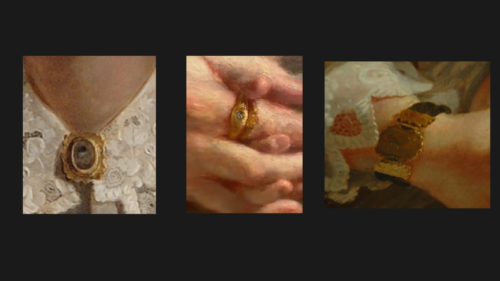

Left: Jane Eleanor Sherman Lacey with Son by Lilly Martin Spenser, circa 1857-1859. Roanoke: Taube Museum. Right: Details of mourning jewelry worn by Jane in her portrait. (Images from B. Scott Crawford’s study, Dating Jane: Domesticity, Death, and Photography in a 19th Century Portrait.)

In addition to installing a prominent monument in the newly constructed Mountain Grove Cemetery for his wife and children, he commissioned a mourning portrait. This striking and important painting from the American female artist Lilly Martin Spenser was likely completed before Rowland married his second wife Elizabeth in 1859. In the work we can see emblems of death such as the cherub vase with its wilting flower along with the mourning jewelry worn by Jane. The brooch with its small portrait of baby Henry along with a relic ring and hair bracelet send the somber message that we are looking at loved ones now lost.

Memorializing death had become an increasingly important part of Rowland’s life and his responsibilities with the Fairfield County Historical Society. We know that he was visiting graveyards throughout the county, and he took on the care and maintenance of several sites, including the Old Stratfield Cemetery located today off Briarwood Avenue in Bridgeport. In some cases, he replaced the gravestones of his family’s ancestors.

Headstones from the Old Stratfield Cemetery that were replaced by Rowland Lacey. On the left is Captain Josiah Lacey’s stone. Though he died in 1812, this stone was erected by Rowland Lacey in 1872. On the right is the stone for Matthew Sherman. It was replaced in 1884. Orcutt studied the site in 1886, so his inventory for this graveyard includes a drawing of the new monument.

We can only surmise that the original monuments were damaged, and their text and their original tablet profiles were transferred to the newer stones. And while their replacement can be seen as act of historic preservation, it is also evidence Rowland’s interest in preserving his family’s early heritage. This is emphasized by the inclusion of his own name at the base of each tombstone.

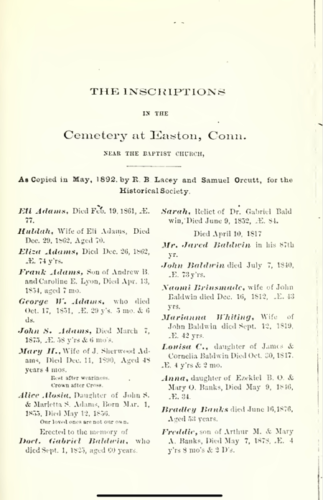

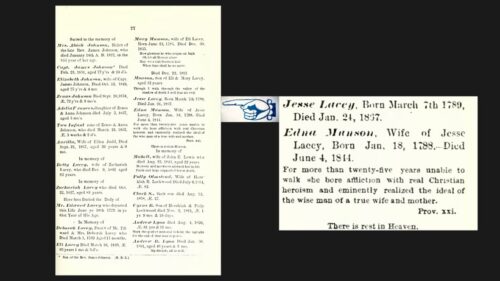

Frontispiece of “Inscriptions in the Cemetery at Easton, Conn. Near the Baptist Church,” as copied in May 1892.

Rowland’s concerns about the losses at historic cemeteries and his ambition to have all the stones in the county transcribed may have led him to encourage Samuel to take on this task when he returned to Bridgeport in April of 1892. This is suggested by the May 1892 date cited on a paper they jointly published listing an inventory of a cemetery in Easton, described only as “near the Baptist Church.” Today, it is known as the Union Cemetery.

Well known to Rowland since his childhood, this hallowed ground was where his paternal grandparents, his parents and certainly many family members and friends were interred. Considering Samuel had not been in Connecticut for several years and had only returned in that April, it seems difficult to believe that this grief-stricken man took to visiting a cemetery for research so soon after his own personal loss. Among the dead listed, over 30% are infants, children, and young adults. Of these deaths, over 70 were under one year of age. While these statistics are not unique to Union Cemetery for this time period, these sorrowful monuments, erected by grieving parents, would certainly not have been the best material for Samuel in his sorrowful state. One would imagine it would have been challenging for Rowland as well.

The timing is another interesting factor, because we know through Samuel’s writings that he took this work very seriously. He wrote that he would spend sometimes more than half an hour deciphering the “lettering of every inscription” taking “very great care” to “go over the whole grounds three times with intention and diligent effort.” So, the question comes to mind, were these two men able to process the hundreds of graves listed in their work between Samuel’s return sometime in April and May of 1892?

Further analysis of their inventory shows that there are no dates later than February 1890. Currently at Union Cemetery there are headstones for the latter half of 1890 as well as a substantial number for 1891. Because of their absence in this inventory, I don’t believe the monuments were “copied” in May of 1892 as the title page suggests.

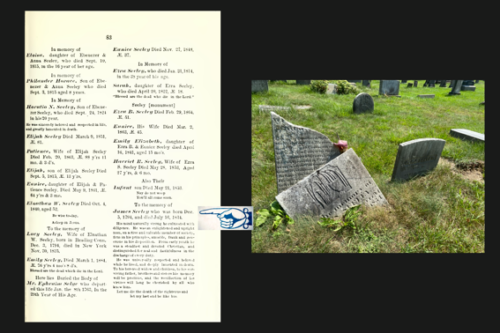

Lacey and Orcutt’s Inventory of Union Cemetery, page 83, detailing James Seeley’s lengthy inscription. On the right, it is difficult to read this stone today in its broken and weathered state. The Union Cemetery is currently in severe need of funds for repairs and restoration and there are many stones in dire shape.

I suspect that while both men contributed to the work, Samuel’s part may have been earlier, perhaps compiled before he left for California in 1890. Rowland, with his close ties to the Easton community, probably added the more recent inscriptions along with his helpful footnotes.

Regardless of how the work was divided or composed, their research has preserved a critical snapshot of over 670 grave markers ranging from 1760 to 1890. Since many of the tombstones today are illegible, we would not be able to read them without this list, particularly the smaller epigraphical passages that often have personal and heartfelt messages that have weathered away. These transcriptions, therefore, offer valuable genealogical and cultural context for scholars.

Lacey and Orcutt Inscription inventory, page 77, with detail of his parents’ headstone inscription indicating personal information not included on the subsequent headstone.

At some point after this inventory was copied, the gravestone for Rowland’s parents, Jesse and Edna, were replaced. We can infer this because their inscription entry refers to a stone that no longer exists. In its place stands one large granite marker in a style similar to the more contemporary monuments Rowland erected at Mountain Grove Cemetery for his family. This does suggest he may have been responsible for the change. The original stone for Rowland’s parents held a detailed inscription regarding his mother who suffered a debilitating ailment for more than twenty-five years. Despite her inability to walk, she was described as an ideal wife and mother. Citing Proverbs, the inscription ends with, “There is rest in Heaven.” No such text exists on the new monument.

Jesse and Edna Munson Lacey’s headstone as it appears today at Union Cemetery.

Perhaps Rowland may have felt his parents deserved a more prominent and durable stone. He would certainly have been be familiar with various materials used and could appreciate the longevity of granite. Whatever the reasoning, the replacement must have been a substantial cost and the new stone would have been seen as an emblem of the family’s success and status in town.

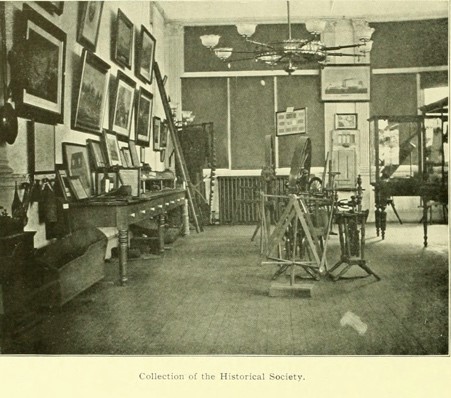

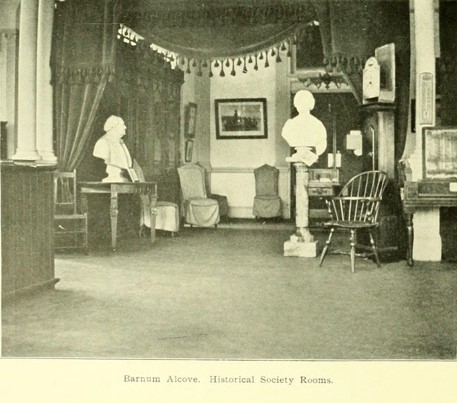

By the end of 1892, both Rowland and Samuel had turned their attention to preparations for the grand opening of the Barnum Institute. Rowland had been in correspondence with P.T. Barnum and other collectors eager to donate items to the museum. These ranged from local indigenous artifacts, colonial housewares, and revolutionary war memorabilia. The walls were decorated with paintings, prints and maps and their reference library was said to include over two thousand volumes.

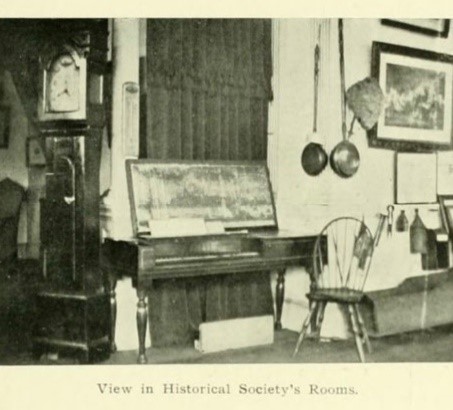

Three views of the exhibition rooms of the Fairfield County Historical Society at the Barnum Institute of Science and History, circa 1897. These would have been the objects and display cabinets that Samuel Orcutt was busy arranging at the time of his death. Images from Standard’s History of Bridgeport.

Samuel, as the newly appointed secretary of the Society, was busy setting up displays in the exhibition space and retrieving packages of donated items. With the opening event a month away, he had gone in person in the late afternoon of January 14th to pick up a valuable parcel from the steamboat company offices on South Avenue. He diligently secured the box on a wagon, and he proceeded to walk back to the building.

Unfortunately, as he came upon the railroad crossing, he did not heed the signals due to his hearing impairment. Clearing one set of tracks with a close call, he failed to notice the fast moving “ghost train” that was barreling through the city on the adjacent rails at that very moment. These trains earned their nickname because they did not stop or take passengers. They ran along the routes simply to clear debris, ice, and snow from tracks, and they were often involved in accidents. Samuel was thrown quite a distance and his skull was crushed above the crown. Witnesses describe his body mangled beyond recognition but amazingly he survived long enough to be placed in an ambulance.

Dying shortly afterwards, his passing added a mournful note to the grand opening of the Society’s new home. Several pages of their annual report for 1893 are dedicated to his life. Since much of Samuel’s family had relocated to California, Rowland saw to all the funeral arrangements and gave a heartfelt eulogy for his colleague and friend. The Society was able to find a burial plot in the Old Stratfield Cemetery. The ancient graveyard had been the subject of much of Samuel’s research and a lovely hill location was acquired.

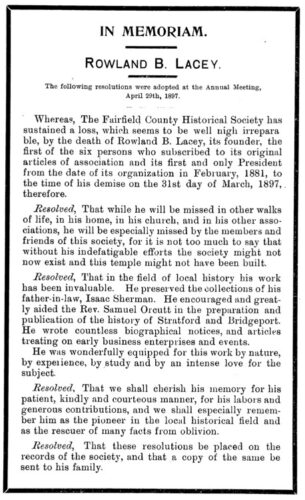

Left: Samuel Orcutt portrait, Fairfield County Historical Society Papers, Bridgeport Public Library, Bridgeport History Center. Right: A photography of Samuel Orcutt’s grave included in the necrology for the Fairfield County Historical Society annual report for 1893. Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library.

A traditional upright tablet marker prominently identified him as “Historian and Genealogist” whose “published works are his monuments.” Contemporary scholars noted that his placement at this historic cemetery was fitting as he rested “among those whose names he sought to preserve from oblivion.”

After Samuel’s death, Rowland continued as head of the Society as he had done for more than a decade. Almost a year after his friend’s death, his second wife Elizabeth died. Three years later, Rowland himself fell ill and died of pneumonia on March 31, 1897.

Surrounded by loved ones, he passed away in a state of severe delirium speaking “unceasingly” on the events of his life. There were however, revelations after his passing that shocked the city for years after his death. The businessman turned scholar badly neglected his own personal affairs. His earlier financial success had fallen on hard times and companies he invested in had failed. It was discovered that he had been embezzling money from trust funds he administered for several estates. The accounting forensics revealed that he misappropriated over 26,000 dollars over the course of decades. (Today that would be almost a million dollars.) And even though there was evidence he intended to repay the funds; the failure of his investments made that impossible. Local newspapers reported the scandal in detail and his assets had to be sold for restitution and outstanding debts.

In Memoriam, Rowland B. Lacey, resolutions published by the Fairfield County Historical Society on April 29th, 1897.0

Though there was little left for his surviving heirs as an inheritance, his fellow Society members had acknowledged him in a solemn resolution. A copy of this text was published in their annual report for 1897 and remains in the Fairfield County Historical Society archives. In it, they recognized him as the essential founder of their organization and leader in preserving history. Calling upon the memory of his friendship and his love of the subject, they wrote:

“…we shall especially remember him as the pioneer in the local historical field and the rescuer of facts from oblivion.”

The specific use of the word “oblivion” in this context for both Rowland and earlier for Samuel was not just a poetic Victorian turn of phrase. Literally meaning today “the state of forgetting” or “being forgotten,” for the 19th century audience steeped in Classical training, this term was more nuanced and symbolic. For them, “oblivion” harkened back to the writings of Herodotus in antiquity, where the word didn’t just mean the loss of knowledge, but specifically a loss of truth. Hence, Rowland was to his colleagues a heroic “rescuer of facts.” The proclamation in his honor places him in a venerable tradition of western historians that sought to preserve truth as a moral imperative.

Regardless of the posthumous revelations that tarnished Rowland’s public legacy, we can appreciate the extraordinary contributions he made along with Samuel Orcutt. These gentlemen truly believed that the most important acts of history were not limited to battlefields or politics. They valued those events that make up the smaller moments in life and could be seen in the day-to-day records of a local community: the ledgers of shops, the entries in church and town registers, and of course, the often-overlooked inscriptions in cemeteries. For them, these primary documents were evidence of what the 19th century historian Maccaulay called the “noiseless revolutions” that profoundly influence our society. And while modern historians owe an enormous debt to Rowland, Samuel and all the early members of historical societies for their labors, in a sad irony, they are almost all but forgotten today.

The Fairfield County Historical Society united with the Bridgeport Scientific Society in 1899 for lack of funds. By 1931, even with this partnership, the organizations were forced to disband after poor membership enrollment. Their limited resources prevented them from paying property taxes and caring for their beautiful building. The remains of their archives and collections are scattered today amongst several institutions including the current Barnum Museum and the Bridgeport History Center.

The Lacey Family Plot and Monument, Mountain Grove Cemetery, Bridgeport, Connecticut.

As for Rowland Lacey, his monumental grave stands in Mountain Grove Cemetery, but few passing by would know of his contributions to history. More troubling is the state of Samuel Orcutt’s grave. Long fallen over, it is slowly disappearing under the grass and soil, waiting to be rediscovered by a new generation of scholars.

Left: Face of Samuel Orcutt’s grave today. Right: Samuel Orcutt’s grave in the foreground view the Old Stratfield Cemetery, Bridgeport.

Bibliography:

Bielawa, Michael, Wicked Bridgeport, Charleston, the History Press, 2012.

Crawford, B. Scott, Dating Jane, Domesticity, Death, and Photography in a 19th Century Portrait, B. Scott Crawford, 2013. https://books.apple.com/us/book/dating-jane/id601887073

Fairfield County Historical Society Reports and Papers, 1882-1897, Bridgeport: Standard Association Printers. https://archive.org/details/reportspapersfai00fair

Orcutt, Samuel. The History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport, v. 1, Fairfield County Historical Society. New Haven, Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, 1886. https://archive.org/details/historyofoldtown01orcu/historyofoldtown01orcu

Standard’s History of Bridgeport, edited by George Curtis Waldo. New York, The Standards Association, F. T. Smiley & Co. 1897. https://archive.org/details/standardshistory00wald/page/n107/mode/2up

Archives:

P.T. Barnum Research Collection (BHC-MSS 0001), Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library. Available online: https://collections.ctdigitalarchive.org/islandora/search/Barnum%20letters%20geneology?type=edismax&cp=110002%3AAdmin001

Records of the Fairfield County Historical Society (BHC-MSS 0097), Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library

Papers of Rev Samuel Orcutt (BHC-MSS 0032), Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library

Newspapers:

Bridgeport Post

Bridgeport Standard

Hartford Courant

Meriden Weekly Republican

Meriden Journal

Haven Morning Journal and Courier

Newtown Bee

Norwich Gazette