When The Aztec Eagle Began Her Soar Over Bridgeport: Part 1

By Abraham Lima

PROLOGUE:

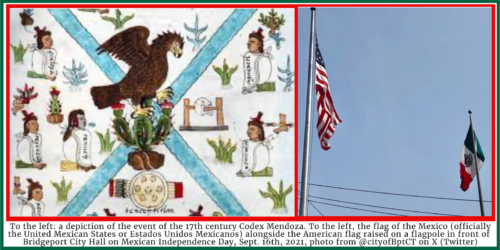

The eagle eating a cactus perched on a snake was the symbol the god Huitlolopotchli gave to nomadic Nahuatl-speaking people as to where to build their new city. They found just that in the middle of Lake Texcoco and thus the city of Mexico-Tenochtitlan arose in the middle of the lake with artificial islands surrounding it.While the Aztec empire did not territorially incorporate all the land of modern Mexico, it is the Aztec eagle from the people that called themselves the Mexica (me-she-ka) that is the symbol of the nation state that adopted for itself the name of these Mexica, or as the Spanish called them, Indios Mexicanos, who gave the land the name, Mexico.

And over her flies the legacy of this eagle the Aztecs saw, the Aztec Eagle, and she soared north

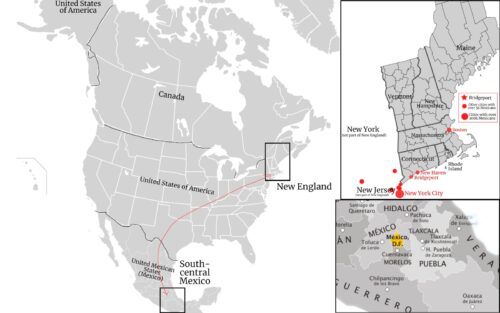

Around 2,000 miles away, in Bridgeport, Connecticut, resides the largest Mexican population, both largest foreign born and Mexican descendant population, of any city in New England, ahead of runners-up Boston and New Haven. Park City became home to another group of the hundreds of ethnic groups that have called these 16 square miles home. Since 2000, they are Bridgeport’s second largest Hispanic or Latino group behind the Puerto Rican community, they make up roughly a quarter of the city’s Hispanic population, and are Bridgeport’s 4th largest ancestry group, behind her very large Puerto Rican, African American, and Jamaican communities.

When, how and why did Mexicans start to arrive in large numbers to Bridgeport? That is the tricky part. But we can observe the regional trends and compare them more introspectively to the once Industrial Capital of Connecticut. Past 1990, Bridgeport Mexican community members themselves were asked, and we’ll combine those first hand sources with others to tell the story.

The Aztec eagle now flies over Bridgeport, and this is the story of how she spread her wings.

New England is the region farthest from the Mexican border in all of the lower 48 states in the USA. Above is a map of the North American landmass showing a land route between South Central Mexico and New England. Source for

base maps is Wikimedia Commons, edited by Abraham Lima. Sources: 2020 Census

This is Part One of a 4 Part Series at the Bridgeport History Center:

- Part 1 “En El Principio, Los Mojados en USA” and “What are Tortillas?”

- Part 2 – “The New Guys in New York” and “Men of Maplewood”

- Part 3 – “Miles y Miles Mas (Thousands and Thousands More)”, “History of the Future” and “The Eagle Soars”

This is part one of a 3 Part series: for origins of the Mexican migration wave and migration patterns to the NYC region and how that played out in Bridgeport, see the next part, Part 2.

CH 1: En El Principio: Los Mojados en USA… the migration begins

This section briefly explains the history of Mexican-Americans in the United States.

Spanish conquistadors who had aided Cortez or had arrived in Mexico City were seeking minerals up north, and Spain laid claims of the area that is today the southwestern states of Texas, California, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada, and some parts of Colorado, Wyoming, Utah and Oklahoma. Missions to convert natives were established, and some racial mestizaje had occurred. The land was very sparsely populated, and Americans were invited in to inhabit the land. The Mexican American War would arise from tensions on land claims in the region.

The 1848 Treaty of Miguel Hidalgo ended the Mexican American War. With the acquisition of the southwest came, along with the Anglo settlers there, the acquisition of the 86,000 largely Spanish descendant Californios and Tejanos. 14,000 Mexican immigrants arrived during the California gold rush in 1852. Under Spanish rule, the traditional communal land system of local indigenous peoples (“ejidos”) were protected. The liberal Mexican government passed the Lerdo Law of 1856 to encourage private property ownership. Along with breaking up church lands, it broke the communal lands into privately-owned lots (in the 1920 census, the only to count race: 59% of Mexicans were “indigenous mixed with white” and 29% were “pure indigenous”). An elite plantation owning class bought most of the land after privatization. In 1910, 98% of central Mexicans, (55% of the population) were landless. In the late 1800s the extensive Mexican rail network built by the peasants connected central Mexico to the border with the United States

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1887 and the Japanese Gentleman’s Agreement of 1909 barred immigration from these countries to the United States, causing a shortage of cheap labor. Average daily wages for rail laying in 1900 were 20 cents in Mexico vs $1 in the United States. Plantation work averaged 12 cents paid in supplies and shelter vs $1.50 as a salary in the U.S. During the Mexican Revolution, one-tenth of the Mexican population migrated to the United States, 700,000 authorized Mexicans entered between 1900-1930 and 87% got agricultural jobs in the rural Southwestern United States. The migrant population came from all over the populated central and south, but primarily migration to the United States came from the Bajio region, composed of the states of Michoacan, Jalisco, Zacatecas, Aguascalientes and Guanajuato.

Due to a labor shortage during World War One, and during the Great Depression, Mexicans moved from the rural southwest to southwestern U.S. cities like San Antonio, Los Angeles, and Phoenix, and formed small communities in midwestern cities connected by rail lines like Pittsburgh, Kansas City, Detroit and Chicago. Mexicans began migrating to work in the city’s industrial rail, steel and meat packaging plants in Chicago. These communities shrank in the 1930s with the mass deportations during the Great Depression. Between 350,000 to 2 million Mexican-Americans, many US born citizens, were deported via rail. The bracero program, created during WWII to meet US labor shortage, brought more Mexican workers to these cities, and the southwestern states and Chicago. By 1950, 39,742 Mexican born people lived in Los Angeles, 71,365 in the greater Los Angeles area, 9,080 in Chicago, and the numbers would grow. A tradition of migration to the United States had been established in varying degrees by region.

2: What are Tortillas? Traces of Mexicans in Latino Bridgeport Pre-1980s

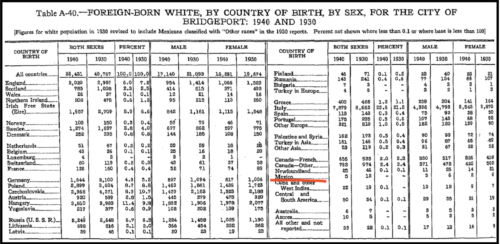

Around this time in history, on the other side of the country, along the New England coast was an industrial Bridgeport, Connecticut. In 1950 it was a city of 160,000 people (230,000 people including the developed parts of Fairfield, Stratford and Trumbull, counted as part of Bridgeport’s urban area), then the 63rd largest US city. With 500 factories, in 1930 around 70% of its population were immigrants or their children, mainly Eastern and Southern Europeans.

The few Mexicans at this time in Bridgeport were women like Elena Cabrera Chandler from San Luis Potosi, who married a Bridgeport-born American and lived at 26 Sturtevant Pl, laborers like Jose Maria Ares of Veracruz, or women of non-Mexican backgrounds born in Mexico, like Syrian origin Sophie Estrella Wakin of Chihuahua, who entered via El Paso and married a Syria born man and lived at 490 Salem St. In the 1930 census, there were “9 Mexicans‘ ‘ counted living in Bridgeport, as mentioned in the 1936 book “The Story of Bridgeport”. Of these, 7 lived at 442 Broad St alone. Ysabel Ruiz, his wife Ygnacia, his stepdaughter Romero Virginia, and Ysabel’s 1 year old New York born grandson Angelo Lomeni. 3 borders lived with them, Emilio Hurtavo, Tony Guerro, and Miguel Jacavo. None had schooling, 2 were literate, all spoke Spanish and no English, most worked “odd jobs” and only tiny Angelo was a US citizen. A decade later in the 1940 US census, two years before the start of World War Two, there were 5 Mexican born people in Bridgeport, 3 men and 2 women. “Central and South America” as one group and “West Indian” were other categories as place of birth. There were 19 people from the West Indies (the Caribbean) and 52 people from Central and South America in Bridgeport that same year.

While several hundred Mexican braceros were hired by the New Haven railroad from 1944 – 45 to fill shortages, and housed in barracks in North Haven, most appeared to have returned home.

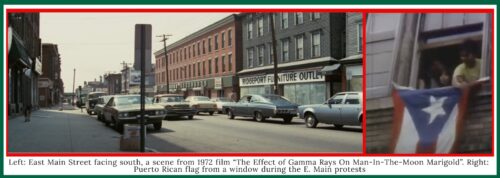

Well, were there other Spanish speakers then? Previously in the early 1920s, a wave of migrants from the Valencia region of Spain had settled in Bridgeport, starting an enclave, but many left in the 1930s. From this point on until 2000, most Hispanics in Bridgeport would be Puerto Rican. In 1910, fewer than 2,000 Puerto Ricans lived in the US, mostly in NYC. The main Puerto Rican center of migration: New York City. In 1945, 13,000 Puerto Ricans were in NYC, but by 1946, over 50,000. Puerto Ricans started communities in Chicago, Philadelphia, Newark, and in New England industrial cities, including Bridgeport. Thousands of Puerto Ricans originally arrived in Connecticut to work in tobacco fields. And by the late 1940s, Puerto Rican, to a lesser degree Cuban families arrived in Bridgeport to work. One quarter of Puerto Ricans coming into Connecticut moved from New York City, almost all the rest came directly from the island. This was the beginning of Bridgeport’s present day Spanish-speaking Latin American community.

Sara Torres, who grew up in the 1940s on State Street, where her Puerto Rican family owned a variety store, travel agency and cinema, was interviewed in 1998 by Mary Witkowski in an oral history interview for the Bridgeport History Center, part of a series called “Bridgeport Working, Voices of the 20th century” . Among other questions relating to her childhood, she was asked “did you notice a bigger influx of people during any particular time?” She said “Well, you know, in the beginning it was just Puerto Ricans and Cubans. Maybe because our club that my father was — but then, it just — our office started going with South America, Mexicans. It was then Hispanic… Then I can see where we all — no matter what — the language we all knew. Different expressions, different words. But it all turned to be — all of us together, Hispanics.”

In the 1950 census only 13 Mexicans were counted in Bridgeport according to the census. Meanwhile, from 1950 and 1955 Bridgeport based companies or factories such as CASCO, ACME Shear and Columbia Records began to advertise job listings for workers in Puerto Rico, a territory of the United States, with Puerto Ricans being birthright US citizens. One of the 13 Mexicans in 1950 was Isadoro Flores, born 1904 in Aguascalientes (within the Bajio region where most Mexicans came from) and via rail arrived at El Paso, Texas in November, 1925 where he entered. He lived in The Bronx and worked as a trucker when he naturalized in 1942, but was living at 280 State St in Bridgeport and worked at Brown and Pollock on Charles St. when he was drafted into World War 2 in May, 1943. After the war, he married a Puerto Rican, had children, worked as a trucker and mechanic, and lived on Lafayette St, but died in a car crash in 1954. His eldest son, also named Isadore Flores, went to Harding High, worked at Textron Lycoming in Stratford and died in 2011. Listed as “blue eyes” with “dark complexion”, Jose Maria Ares of Veracruz, who entered by ship at Key West, Florida from Havana, Cuba, lived in Dayton St and worked for UI when he was drafted into the war. His son attended Stratford High and worked at a Milford clock factory. Maria Duato from Leon married a Spaniard from Valencia in Cleveland and moved to Bridgeport. They lived on Loraine St and moved to Arizona in 1965.

In terms of Mexican origin people, only 32 people were counted in the following decade, in 1960. But by 1967, a New York Times article stated 10% of Bridgeport’s population was Puerto Rican, or around 15,600 people. East Main Street lined up with Spanish language storefronts, cinemas and services. That decade, in comparison, only 158 Mexican-born people were counted in the entire state of Connecticut, 596 in New Jersey, and 4,135 in the whole State of New York. In major East Coast cities that decade, 3,433 Mexican born people lived in New York City according to the census, 50 in Boston, 256 in Philadelphia, and 352 in Washington D.C. In 1968, 90% of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in the United States lived in just 5 states, all of them in the southwest: California, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. There were 5 million of them, the second largest minority group in the United States after African Americans.

Part 2 will contain chapters 3 and 4. It will be on the start of New York’s modern Mexican community, migration patterns and the stories of the early “pioneer migrations” of Bridgeport’s modern Mexican community.

For Part 2, Click Here: https://bportlibrary.org/hc/business-and-commerce/when-the-aztec-eagle-began-to-soar-over-bridgeport-part-2-the-new-guys-in-ny/

Bibliography:

-According to the paper “Pathways to El Norte: Origins, Destinations, and Characteristics of Mexican Migrants to the United States”

-Ideal Education Group. “The Flag of Mexico.” Don Quijote. Accessed February 10, 2024.

-https://www.donquijote.org/mexican-culture/history/mexico-flag/.

-Ian Mursell. “The Eagle and the Snake…” Mexicolore. https://www.mexicolore.co.uk/aztecs/ask-us/eagle-and-the-snake

-Leco Tomás, Casimiro, and Orlando Fierro Rodríguez. Migración Internacional en Guerrero a Estados Unidos, Julián Blanco, Municipio de Chilpancingo.

-SiUS. “Spanish Immigration to Bridgeport, Connecticut.” Spanish immigrants in the United States. https://spanishimmigrantsintheus7.wordpress.com/2013/03/27/spanish-immigration-to-bridgeport-connecticut/.

-“Mexican Immigration .” U.S. Immigration and Migration Reference Library. – Encyclopedia.com. 7 Feb. 2024 <https://www.encyclopedia.com>.

-Arredondo, Gabriela, and Derek Vaillant. “Mexicans.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. Accessed February 10, 2024. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/824.html.

–Mexican-Americans: The Invisible Minority. Produced by Joseph Louw. Narrated by Ernesto Galarza. National Educational Television, 1969.

-U.S. Census Bureau (1970). New York General Population Characteristics, 1970 Census of Population

-Retrieved from https://usa.ipums.org/usa/resources/voliii/pubdocs/1990/cp1/cp-1-34-1.pdf

-Time Staff. “1930s: Repatriation of Mexicans – Ana Minian.” Stanford Department of History. Last modified June 25, 2020. Accessed February 10, 2024. https://history.stanford.edu/news/1930s-repatriation-mexicans-ana-minian.

-Kandell, Jonathan. “Jobs Elude Bridgeport’s Puerto Ricans.” The New York Times, June 11, 1972, N4.