Did Jack the Ripper Visit Bridgeport? Who Was the Mysterious Fred B. Beleno?

by Michael J. Bielawa

One hundred and thirty years ago this autumn, in 1888, Jack the Ripper terrorized the Whitechapel neighborhood of London, England. The madman brutally murdered five women. Then vanished. Never to be heard from again. Or was he? Some 21st century Ripperologists, as Jack the Ripper investigators are dubbed, think that the unknown assailant journeyed to America. Did Jack the Ripper voyage to Bridgeport, Connecticut?

It was Sunday, December, 20, 1903. The woman had been dead for half a day. Her body was discovered in the seedy three-story Kelly Hotel in Manhattan’s waterfront district. Sarah Martin was her name. Here on the rough streets along the East River she was known for the past fifteen years as Cob Dock Sallie. The cobblestone warren of alleyways was not unlike Whitechapel. And just like the Ripper’s London victims Sarah Martin was a prostitute. Detectives examined her remains. The Martin woman had been strangled, slashed and then mutilated. The headline from the December 21, 1903 Bridgeport Evening Farmer shouted, “’JACK THE RIPPER,’ NOW UNDER ARREST…” The article also remarked that “the way the [crime]was accomplished, suggests the Whitechapel murders.” New York City papers noted how this violent act resembled a murder which took place twelve years prior, in 1891, in the same Cherry Hill section of the city. In that case, Carrie Brown a prostitute by the street name “Old Shakespeare” (from her propensity to recite the Bard whenever she was intoxicated) was butchered in the same manner merely a block from where Sarah Martin was discovered.*

Detectives recreated a timeline of Sarah Martin’s final hours. On Saturday, December 19, 1903 at approximately 10:30 at night, an unidentified man walked into the Kelly Hotel (in a bit of lost Gotham vernacular this was known as a “Raines law hotel” which meant that according to New York State law alcohol could be served to lodgers on Sundays). The stranger who entered the ramshackle hotel was about thirty-five years old, five feet nine inches tall, broad shoulders, high cheek bones, blonde hair and a light mustache. Witnesses at the hotel bar said he looked Swedish. They all agreed that there was something unnatural about the man’s eyes; a disturbing “peculiar” or “wild” quality. After sharing a table and a couple of rounds of drinks (he drank beer while Sarah threw back whiskey) the couple requested a room. They registered as “Carl Nilson and wife” (some newspapers stated the name was “Nelson”). Interestingly, the New York Times (December 21, 1903) reported that the signature in the register was so poorly written that the police initially conceived the name as: Carl “Alvinson” or “Aldesen.” About midnight Sarah ordered more whiskey. The bottle was delivered to the room by the cleaning lady, Jennie Starr; Sarah and Jennie shared the whiskey in the hallway. When asked, Sarah told the chamber maid that the man was asleep. It was the last time anyone outside of that room saw Sarah Martin alive.

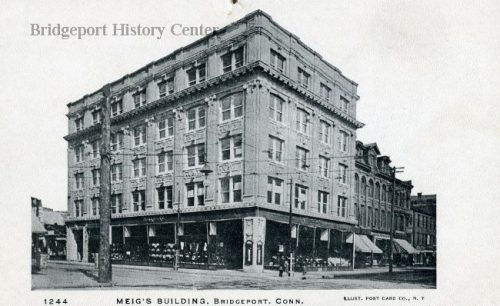

Meig’s & Co. building

The next afternoon a cleaning woman (some say Jennie Starr), others report it was Mrs. Kelly, the wife of the hotel proprietor, found the body. Thinking Sarah was asleep the woman nudged the prone shape. Odd, Sarah was so cold. Pulling back the sheet the brutal crime became obvious. Sarah’s throat was slit and she was gashed across the chest from armpit to armpit. There were other wounds, to the abdomen and “several in other parts of the body” which later court documents hinted at, but for decorum’s necessity remained unmentioned. Police searched the hotel room for clues. They discovered two bundles: one holding a couple of soiled shirts and a second box containing an old pair of shoes. Scrawled in pencil on the wrapping paper outside the shoebox was the name “Fred B. Beleno.” Detectives also gathered two crumpled sales receipts on the floor, one for a $3.00 sweater and the other for a $2.50 pair of shoes. The stationery bore a name: “Meigs & Co., Bridgeport, Conn.” New York Police Inspector McClusky immediately dispatched detectives McCafferty and Chandler to the Park City. Their mission: locate and apprehend the elusive Mr. Fred B. Beleno.

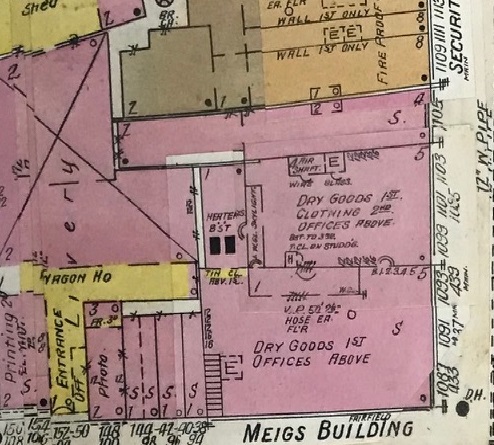

Meig’s Building block

Meigs & Co. was a popular retailer located in the heart of the Bridgeport shopping district. The clothing store was filled with Christmas shoppers when New York City investigators questioned the clerks. Seems the suspect was memorable even amidst the holiday throng. The detectives spoke with Parker T. Silvernail who sold the suspect a blue sweater. Louis T. Baldwin was the clerk who helped with the unidentified man’s shoe purchase. Baldwin distinctly remembered the odd-cobbled shoes the man wore when he came into the store: they had a homemade repair job of copper tacks arranged in the right sole allowing space for the man’s painful corns… and the shoes resembled those worn by sailors. The suspect stood out from the overflow of customers in the hectic store for another reason; he shared a sad tale with the shoe salesman about being shipwrecked off of Cape Cod and spending an extended time recuperating at New Haven Hospital.** The police anxiously made their way to Bridgeport Harbor. They inquired about Fred Beleno, the name written on the wrapping paper found in Sarah’s hotel room.

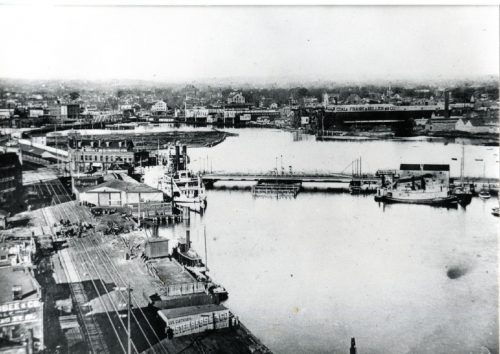

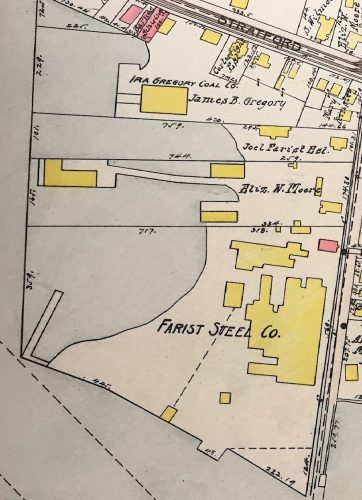

The authorities were surprised to discover that “Fred B. Balano” was not a man’s name at all, but rather the name of a schooner. The vessel was unloading lumber at the Farist Dock located at the foot of East Main Street. Captain Orlando C. Sawyer told the police that he had discharged deckhand Carl Nilson on Saturday, December 19. It was learned that the suspect departed for New York by train.

Detectives McCafferty and Chandler excitedly telephoned the news back to their boss in the city. Headquarters arranged a stakeout of the most likely place a sailor might be found. Police went to the Sailors Union on South Street, New York City looking for a blonde man wearing a blue sweater and new shoes.

Portion of Bridgeport Harbor, late 19th Century

The suspect was immediately located. The man they approached admitted he sometimes used the name Carl Nilson when signing aboard ship, it was his mother’s maiden name, and was easier to employ than his true name, Emil Totterman. Totterman explained that he was thirty-three years old and had been born in Finland. He denied ever visiting the Kelly Hotel or knowing anyone by the name of Sarah Martin. And Totterman vehemently denied killing anyone. But Totterman’s shoes told a different story. They were stamped, “Meigs & Co.”

A parade of witnesses identified the blonde sailor. Folks at the Kelly Hotel and the Meigs clerks all recognized Emil Totterman, alias Carl Nilson. His handwriting matched the hotel register. A sailor’s clasp knife was found on his person dotted with human blood stains. Totterman’s clothes also proved to contain blood.

The trial took place in early 1904. Totterman smiled horribly when brought to court for sentencing. When the Judge pronounced the decision that Totterman should die in the electric chair the condemned prisoner “burst out laughing.” Totterman was “still laughing when he was taken out of the

Farist Dock

room.” He was transported to Sing Sing State Prison on March 2, 1904.

However, within a few months Totterman’s sentence was commuted. Due to his valor aboard the battleship USS Iowa, and in Cuba, during the Spanish American War Totterman had been awarded three medals, including a citation for life-saving from Congress. As a result of Totterman’s bravery in the US Navy he was granted leniency. The sailor would spend the rest of his life in prison. But this tragic and bizarre tale was far from over. Emil Totterman escaped from Sing Sing in August 1916 while working in the “honor camp” at a convict farm outside the penitentiary’s walls. During Totterman’s time on the run Bridgeport police felt that there was a chance that the escapee lurked in the Park City. Frightening headlines in the local press shouted how a fervent police “dragnet” hounded the Ripper here in Bridgeport. In a terrible coincide, during Totterman’s eight months on the lam authorities questioned whether he was implicated in another Bridgeport slaying. Michael Yorko, a one-legged man, was butchered in Bridgeport on October 22, 1916. The unfortunate victim had been mutilated in the same manner as Old Shakespeare and Sarah Martin. Yorko was found naked in a field near Railroad and South Avenues; he had been disemboweled and nearly decapitated. Totterman was recaptured during April, 1917 in Buffalo, New York and returned to Sing Sing.

Behind bars Totterman continued his sentence as a model prisoner. His name again appeared in newspapers when, during Memorial Day 1927, he adroitly scampered up the towering height of Sing Sing’s damaged flagpole to reattach the American flag. To the cheers of fellow inmates Totterman unfurled Old Glory for three hundred World War One imprisoned veterans. Just over two years later the governor of New York began a review of Emil Totterman’s case. It was decided that Totterman’s case involved circumstantial evidence and the fact that Totterman was intoxicated at the time should have ruled the crime as murder in the second or third degree. The lifer was pardoned. Officially the decree took effect on Christmas Eve 1929. The New York governor was Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Totterman returned to Finland and was never heard from again.

Yet the question remains, if it wasn’t Emil Totterman, then who murdered Sarah Martin?

There has been a lot of discussion among Ripperologists regarding whether Emil Totterman’s age configures to his being old enough in 1888 to commit the crimes associated with Jack the Ripper’s killing spree. According to government documents and newspaper interviews Totterman’s year of birth has been assigned various dates ranging from 1861, 1863, 1870 and 1875. Assuming the former year, Totterman would have been twenty-seven years old during the London murders and forty-two years of age when he was in Bridgeport. Totterman’s own World War One draft registration (which was completed while in prison) states he was born on April 28, 1870 which would have made him an estimated eighteen years of age during the Whitechapel atrocities. Old enough to be Jack the Ripper.

There is a list. An inventory of evil. A ghastly catalog compiled over a century of intense investigation which gathers the names of likely Jack the Ripper suspects. Ripperologists carefully mull over this dark litany of demons. One of whom may have been the infamous Jack. Included among these suspected Rippers there appears the name Emil Totterman. Emil Totterman, who beyond any shadow of a doubt did walk the streets of Bridgeport.

* An April 25, 1891 article in The Day (of New London, CT) entitled, “Jack the Ripper Again” states “The strong probability that London’s fiend in human form, “Jack the Ripper,” has transferred his field of operations from Whitechapel to the slums of New York has sent a thrill of horror throughout the metropolis.” In the case of Carrie Brown, a French speaking Algerian, Ameer Ben Ali, was arrested, convicted, and sentenced to a mental institution. Eventually he was declared innocent of the crime.

** Authorities contacted New Haven Hospital to ascertain if the suspect had indeed been a patient at the facility. A person by the name of John Anderson, who did survive a shipwreck, fit the physical description of the man being sought. He had convalesced at the hospital for a head injury during 1904. Strangely, the “Anderson” name employed by the hospital patient resembles the name the New York police first thought was written in the Kelly Hotel register: “Alvinson” or “Aldesen.”

Sources

Bridgeport newspapers on microfilm, including Bridgeport Evening Farmer, Bridgeport Evening Post and Bridgeport Morning Telegram and Union [available on microfilm at the Bridgeport History Center]

Ansestory.com; Emil Totterman’s Sing Sing State Prison documents. [available at all BPL locations]

New York Times [no subscription fee necessary, NYT microfilm is free at BPL]

***************

Images:

Emil Totterman’s 1904 mugshot from the New York Sun (personal collection)

Meig’s & Co. Building (BPL HC postcard)

Meig’s store location from Sanborn Insurance Map (BPL HC)

Farist Dock at the foot of East Main Street from Sanborn Insurance Map (BPL HC)

Bridgeport Harbor c. 1900 (BPL HC)