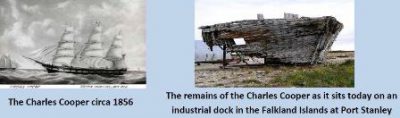

The Charles Cooper: The Only Surviving American Packet Ship

By Robert Foley

The Charles Cooper was built in Black Rock, Connecticut in 1856 and is the only surviving American ship of its kind in the world. It is the best surviving wooden square-rigged American merchant ship. Built for New York’s South Street packet trade, the vessel voyaged around the world during the golden age of sail, and when it could sail no longer, became a floating warehouse for nearly a hundred years on an island off South America. The ship sailed for a decade from 1856 to 1866. It carried cotton to England, salt to India, gunpowder ingredients to the North during the Civil War, and brought European immigrants seeking economic opportunity and freedom in America. The Charles Cooper began with regular fixed schedules between New York and Antwerp. Then, with the outbreak of the Civil War, it no longer had set published departure times and instead voyaged based on spot demands from America to Europe and Asia.

Since colonial days, sailing ships were the backbone of the American economy with trade depending on seafaring commerce along coastal waters to foreign lands. Much is still to be learned of our maritime heritage. The goods the Charles Cooper imported and exported can provide information on the needs and demands of people at the time. The ten years that the ship sailed coincided with the last decade of the packet ship era before the rise of steamships. In fact, the vessel was the very last packet ship to ever sail out of New York City, according to the New York Times. When the South Street Seaport museum was at its inception, its founders purchased the Charles Cooper to be a central feature of plans to restore the historic seaport. However, it was later deemed too fragile to be moved to New York.

The Charles Cooper is the only surviving mid 19th century American packet ship. Packet ships dominated transatlantic trade. They sailed with published schedules instead of departing only after loading the cargo, as was the usual practice. Passengers could depend on a regular schedule for the first time instead of enduring uncertain delays. Named after postal mail packets, the ships carried trade goods and immigrants from Europe.

It is an exceptional packet ship in its construction, built solid and sturdy with a heavily reinforced hull. This may have been to compensate for the loss of the shipbuilder’s first vessel, the Blackhawk clipper ship, which sunk on the first day of its Black Rock launch.

The New York Journal of Commerce, predecessor of Associated Press news, reported that the Charles Cooper is “the most important American Sailing ship surviving from the 19th Century…it is hoped that her remarkably well-preserved wooden hull can someday be placed on exhibit in the port of New York.” The vessel has been the focus of continued research by maritime scholars.

The Charles Cooper was larger than average in size with three marvelously large square full rigged masts. Weighing 977 tons, the ship is 166 feet long, with a beam of 35 feet and 10 inches. Although nothing survives of the rigging, scholars say there were miles of rope and hundreds of blocks to control the massive cotton canvas sails, which required nonstop maintenance by the ship crew. The craft had a bowsprit or wood pole extending from the most forward part of the vessel, which was made of one tree. The frames of the ship were made of American chestnut, the hull of live oak, the beam of Norway pine, as were the main and tween deck beams. Between voyages the vessel was usually ‘coppered’. This was to prevent deterioration of the hull, a constant problem with wooden ships, which were impacted from the corrosive effects of salt water.

The first owners of the Charles Cooper were a sail maker and merchant, William Laytin and John Ryerson, located at Wharf 21 on the South Street on New York City’s East River, where all other major packet lines were based. The owners were a family merchant business as most of the shipping firms were at the time. There were seven different shareholders with ownership divided into sixteenths including some Bridgeport shareholders. Ownership of the ship would change hands several times during the life of the ship.

The shipbuilder, William Hall, originally from Maine, moved to Black Rock where shipbuilding had already been in existence for a century. He bought up all four major shipyards, which were owned by Captain John Brittin, Verdine Ellsworth, Surges & Clearman, and Elizabeth Wilson. Hall’s shipyard was located across from where his house still stands today on Ellsworth Street.

The ship was newsworthy from the moment construction was completed. The event was reported in the New York Herald on November 1856: “Mr. Wm Hall will launch this morning at 10 o’clock, from his yard at Black Rock… she is intended for Messrs Laytin & Hurlbut’s line of Antwerp packets”. Antwerp, the main port in Belgium, had become an important commercial center after gaining independence from Spain. In January 1857, the Charles Cooper departed on its very first voyage from New York. It took seven weeks to cross the Atlantic Sea and arrive at Antwerp. The vessel carried cotton, flour, pearl ash, rosin, logwood, hogs heads of tobacco, bacon, coffee, lard, beeswax, barrel staves, and nails. It stayed in Antwerp for seven more weeks while goods were removed and new cargo loaded.

Departing Belgium for America in April 1857, the cargo included Belgium glassware, wine, hair for wigs, tin, lead, zinc and chloride. In addition, there were 287 German passengers onboard. The number of passengers never exceeded that of this first voyage although was allowed, per shipping regulations, to carry a maximum of 488 passengers based on the vessel’s weight.

The Charles Cooper had accommodations for twelve first class passengers in the pleasant ‘staterooms’. On its first return voyage from Europe, there were nine first class passengers, of which five were merchants and one a doctor. In the back of the ship there was a central saloon. Less well off passengers stayed in the ‘steerage’ lower deck. Their care was regulated by recently passed 1855 U.S. Passenger Act, which required provisions for a certain amount of space, food and water. For example, each passenger was given rations including sixty gallons of water, twenty pounds of biscuits, a pint of vinegar and ten pounds of pork. Websites today list the actual immigrant names on the Charles Cooper, dates of entry, occupations, children, marriage, country of origin and ethnicity.

The ship was able to complete a total of four round trips from New York to Antwerp with the same type of cargo and number of passengers similar to the first trip. The last return trip from Europe stopped in Marseille, France, and Livorno, Italy, to arrive back in America in January of 1860. At this point the ship was three years old and went up for sale.

With the new owner, a Boston dry goods merchant, the vessel never sailed to Antwerp again. Instead, it was advertised as sailing the ‘Dispatch Line’ from New York to New Orleans. Then in November 1860, it departed for Liverpool, England loaded with bales of cotton, sacks of corn, and hogshead size barrel staves. At the time, cotton was such a valuable product imported at Liverpool, that eleven other ships arrived from New Orleans on the very same day. However, trade with the South was growing more risky. When the ship arrived in Liverpool on December 26, 1860, South Carolina had just ceded from the Union. With the onset of the Civil War, it was necessary to find other port locations for trade.

At Liverpool a cargo of salt from was loaded for delivery to India’s main port, Calcutta, capital of the British colonies. The cargo was from England’s oldest salt mine located fifty miles outside Liverpool and had been in use by ancient Romans. The ship returned from India with cargo that included goatskins, hides, gunny cloth sacking, jute, indigo and over two thousand bags of saltpeter, the key ingredient for gunpowder. The trade on this voyage had been financially rewarding.

From 1864 to 1866 the Charles Cooper circled the entire globe, including Australia, India and Guam. In its next voyage, the ship was loaded with coal in Philadelphia and San Francisco was its destination. It never arrived.

The Panama Canal, which facilitated passage from the East to West coasts was not built yet, so merchant ships were forced to round the southern tip of South America at Cape Horn, where wind conditions are severe. It was there, with an already weakened ship hull after a decade of voyages, that the ship was damaged with a leak beyond repair. It managed to reach the nearest refuge, the Falkland Islands, known as graveyard of 19th century American ships. The ship was condemned and purchased by the Falkland Island Company. For almost a hundred years it was positioned prominently in the middle of Stanley port and was used as a floating warehouse. The proximity of the island to Antarctica may have helped to preserve the ship, given the ice-cold waters of the Falkland Islands.

In 1968, the Charles Cooper was purchased by the South Street Seaport museum for five thousand dollars. The museum made three trips with maritime scholars to study the vessel in 1976, 1978 and 1981. However, when the Falklands Island Museum and National Trust was founded in 1991, the South Street Seaport museum decided to return ownership of the vessel to the Falklands Islands.

In 2003, a complete account of the ship’s history was published by Liverpool’s Merseyside Maritime Museum, detailing its construction, owners, cargo and history. Also in 2003, the Falklands Island Museum began removal of the ship from seaport. Today, the vessel is mounted on a support frame on land in the Falkland Islands. There are plans to install it in a museum where all can visit this most historic vessel.

Sources:

Charles Cooper, The Last Emigrant Ship, by Michael Stammers (Liverpool, UK, National Museums & Galleries on Merseyside, 2003)

Cooper Ship Wrecked, by Bill McDonald, Connecticut Post, April 26, 2003

Museum Hopes to Save Old U.S. Ship in Far Port, New York Times, March 24, 1981

Saving a Packet Ship, The Bridgeport Post, March 30, 1981

The South Street Seaport Historic District Designation Report, 1977, NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission

The Charles Cooper Sets Out from Calcutta, 1861, Sea History Magazine, published by the National Maritime History Society July, 1976

The Last South Street Packet, South Street Reporter, March, 1970.

South Street Hopes to Save Historic Ship, Historic Fisherman, February 1969

South Street Acquires Charles Cooper Hulk, South Street Reporter, November 1968

The Falkland Islands Museum and National Trust, website:

http://www.falklands-museum.com/charles-cooper.html