Monuments Everlasting – Bridgeport’s Monumental Bronze Company

By Carolyn Ivanoff

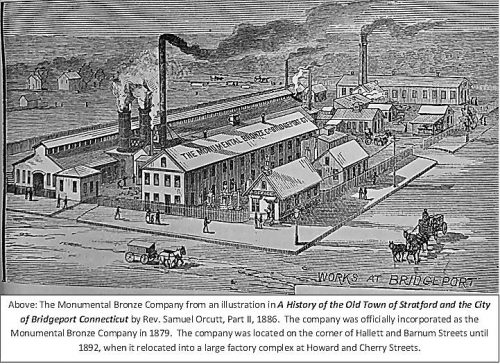

The industrial powerhouse that was Bridgeport during the 19th and 20th centuries made its mark world- wide with many, many products. Bridgeport manufactured everything: sewing machines, cars, phonographs, typewriters, corsets, submarines, machine tools, munitions, every product imaginable. Many of these products were common to the national and world needs of the times, but several products were absolutely unique. The Monumental Bronze Company, on the corner of Howard and Cherry Streets, fulfilled an exclusive and distinctive place in American manufacturing. It was the only company in the nation that cast metal tomb stones from “white bronze.” Every white bronze marker was made to order and, therefore, one of a kind. The company also cast numerous Civil War monuments that can be seen in cemeteries, on town greens, and court house squares all around the nation in thirty states, north and south. White bronze contained no bronze at all. It was almost pure zinc alloyed with tin, but white bronze sounded so much more elegant and sophisticated than zinc and the name made monuments more marketable.

wide with many, many products. Bridgeport manufactured everything: sewing machines, cars, phonographs, typewriters, corsets, submarines, machine tools, munitions, every product imaginable. Many of these products were common to the national and world needs of the times, but several products were absolutely unique. The Monumental Bronze Company, on the corner of Howard and Cherry Streets, fulfilled an exclusive and distinctive place in American manufacturing. It was the only company in the nation that cast metal tomb stones from “white bronze.” Every white bronze marker was made to order and, therefore, one of a kind. The company also cast numerous Civil War monuments that can be seen in cemeteries, on town greens, and court house squares all around the nation in thirty states, north and south. White bronze contained no bronze at all. It was almost pure zinc alloyed with tin, but white bronze sounded so much more elegant and sophisticated than zinc and the name made monuments more marketable.

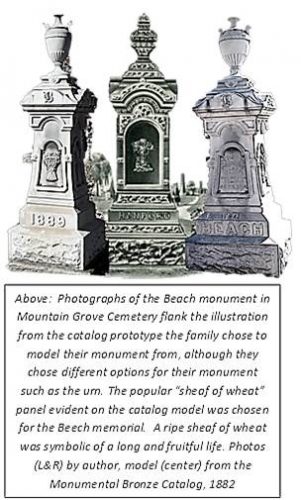

To create a white bronze monument casts were made from wax and plaster and sand molds were made for the molten zinc. The process created various panels that were fused together and assembled into a finished monument with molten zinc at the seams and screws. The completed monument was then sandblasted to create a granular stone-like look and lacquered with a secret formula to chemically oxidize the metal creating a distinct blue-gray patina. White bronze does not rust or wear and never needs painting. Monuments could be a few inches, a few feet, or quite imposing in height. Every white bonze monument was made to order by the customer and each was one-of-a-kind. The monuments were sold by salesmen with extensive catalogs that allowed mixing and matching of panels, shapes, sizes, medallions, portraits, busts, and symbolic artwork. Words, names, dates, sayings, prayers could be cast in infinite forms. Buyers could design the base, central monument, a topper, a statue, or could mix and match many of the standard catalog pieces and examples to form a beautiful, lasting tribute to their loved ones. The monuments could be ordered from anywhere in the nation. The castings would be made in Bridgeport and shipped to the desired location where they were assembled. The advertising for white bronze was compelling. Consumers could save money, get a more artistic design and a more enduring monument than they could with any type of stone. White bronze was maintenance free. It never had to be painted, no moss would grow, and no cleaning was ever needed. Advertising claimed no cracking or crumbling and that white bronze was more lasting than stone.

To create a white bronze monument casts were made from wax and plaster and sand molds were made for the molten zinc. The process created various panels that were fused together and assembled into a finished monument with molten zinc at the seams and screws. The completed monument was then sandblasted to create a granular stone-like look and lacquered with a secret formula to chemically oxidize the metal creating a distinct blue-gray patina. White bronze does not rust or wear and never needs painting. Monuments could be a few inches, a few feet, or quite imposing in height. Every white bonze monument was made to order by the customer and each was one-of-a-kind. The monuments were sold by salesmen with extensive catalogs that allowed mixing and matching of panels, shapes, sizes, medallions, portraits, busts, and symbolic artwork. Words, names, dates, sayings, prayers could be cast in infinite forms. Buyers could design the base, central monument, a topper, a statue, or could mix and match many of the standard catalog pieces and examples to form a beautiful, lasting tribute to their loved ones. The monuments could be ordered from anywhere in the nation. The castings would be made in Bridgeport and shipped to the desired location where they were assembled. The advertising for white bronze was compelling. Consumers could save money, get a more artistic design and a more enduring monument than they could with any type of stone. White bronze was maintenance free. It never had to be painted, no moss would grow, and no cleaning was ever needed. Advertising claimed no cracking or crumbling and that white bronze was more lasting than stone.

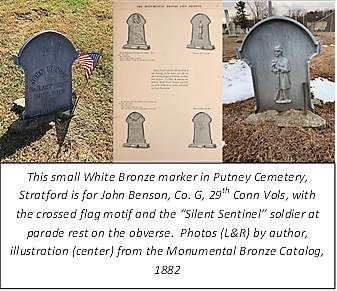

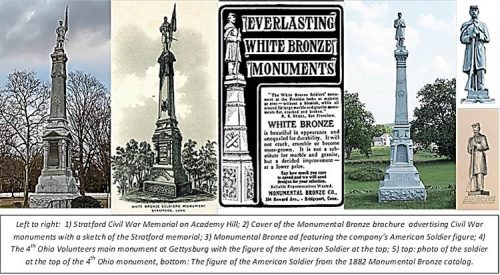

A significant and public part of the Monumental Bronze Company’s business went to memorializing the Civil War. The company featured a catalog that promoted statuary that was suitable for north and south and one of their Civil War memorial brochures featured the elaborate Civil War memorial that was  erected in Stratford, Connecticut by the company in 1889. This elaborate figure of a standard bearer was 35 feet high and the base, pedestal, and figure are all cast white bronze. The Stratford monument was not the usual memorial, however. The stock and trade Monumental Bronze soldier’s memorial featured the figure of the “Silent Sentinel” or what the company catalog called the figure an American Soldier. This universal memorial was a mustachioed soldier in a great coat at parade rest with both hands around the barrel of his rifle. The bluish-gray color of the white bronze could conveniently represent the uniform of either north or south. The southern state memorials eventually gave their Confederate soldiers a slouch hat and a short shell jacket rather than the great coat and Union knapsack.

erected in Stratford, Connecticut by the company in 1889. This elaborate figure of a standard bearer was 35 feet high and the base, pedestal, and figure are all cast white bronze. The Stratford monument was not the usual memorial, however. The stock and trade Monumental Bronze soldier’s memorial featured the figure of the “Silent Sentinel” or what the company catalog called the figure an American Soldier. This universal memorial was a mustachioed soldier in a great coat at parade rest with both hands around the barrel of his rifle. The bluish-gray color of the white bronze could conveniently represent the uniform of either north or south. The southern state memorials eventually gave their Confederate soldiers a slouch hat and a short shell jacket rather than the great coat and Union knapsack.

To commemorate their sacrifice at Gettysburg, the 4th Ohio Volunteer Regiment ordered their monuments from Monumental Bronze. The company provided the regiment with the “Silent Sentinel” figure at the top of an ornate, custom white bronze pedestal. Pedestals could also be of granite or marble but the Ohio boys, like the Town of Stratford, Connecticut went all in for a complete white bronze monument. The 4th Ohio also chose to have the Monumental Bronze Company cast their flank markers and a smaller monument to Companies G and I along the Emmitsburg Road. The smaller monument was chosen from the standard White Bronze catalog. The beauty of these monuments for consumers was the endless customization features and a cost much less than true bronze, granite, or marble. The chosen design options were cast and the castings were shipped to whatever location was desired and assembled on the spot. Advertising that touted White Bronze as cheaper more lasting, and more durable than stone was quite convincing and everyone could see the monuments were beautiful.

White bronze monuments, on the whole, weathered well over the years. However, not all the company’s advertising was correct. White bronze was not as “enduring as the pyramids” as one advertisement claimed. Zinc is brittle and after over 100 years the most common problem for many monuments is breakage, especially on surface castings. Thinner castings are also easily dented.

The smaller monuments have proven to be quite stable and durable. The biggest threat to smaller funerary monuments is vandals smashing in or detaching the panels. Urban legend was that bootleggers and criminals would enter cemeteries at night to stash their illegal booze or ill-gotten gains inside the hollow white bronze monuments by unscrewing the panels. Over time the larger more elaborate monuments are subject to “metal creep”. The Stratford Civil War memorial and the 4th Ohio monument at Gettysburg are prime examples. These tall monuments required extensive restoration due to the fact they began to lean. Larger cast monuments, especially those with white bronze pedestals, are subject to “creep” because the weight of the monument bears down on the base and it begins to bow and bulge, list and lean, ultimately the seams of the base crack and separate due to stress. This slow aging process requires that the hollow monuments undergo extensive restoration by placing a steel support structure inside to support the upper weight. One of the biggest threats to white bronze memorials was that older, poorer choices for restoration included filling the hollow monuments with cement to try to stabilize them which only caused more damage to the structure.

White bronze monuments can be seen in cemeteries throughout the U.S. Their bluish gray color remains quite attractive and distinct. To many cemetery aficionados white bronze monuments are iconic. They  are a genealogist’s dream as their cast panels, letters, and dates are as crisp and clear as the day of installation. The company manufactured made-to-order monuments and markers from 1873 until 1914 with the advent of World War I when the U.S. Government determined zinc to be an important war-time metal. In 1914 the government took the company over to produce gun mounts. The production of grave markers and monument casting ceased. The company did, however, continued to produce custom cast panels to update existing grave markers until it went out of existence in 1939. The desire for white bronze monuments faded with the desire for more granite and marble cemetery stones. Over time monuments developing “metal creep” provided granite and stone companies traction in agitating against white bronze as a cheap alternative to stone. Ultimately granite and stone companies were successful in their attempts to have many cemeteries ban white bronze monuments. After the erection of the 4th Ohio monument at Gettysburg white bronze monuments were banned from the battlefield.

are a genealogist’s dream as their cast panels, letters, and dates are as crisp and clear as the day of installation. The company manufactured made-to-order monuments and markers from 1873 until 1914 with the advent of World War I when the U.S. Government determined zinc to be an important war-time metal. In 1914 the government took the company over to produce gun mounts. The production of grave markers and monument casting ceased. The company did, however, continued to produce custom cast panels to update existing grave markers until it went out of existence in 1939. The desire for white bronze monuments faded with the desire for more granite and marble cemetery stones. Over time monuments developing “metal creep” provided granite and stone companies traction in agitating against white bronze as a cheap alternative to stone. Ultimately granite and stone companies were successful in their attempts to have many cemeteries ban white bronze monuments. After the erection of the 4th Ohio monument at Gettysburg white bronze monuments were banned from the battlefield.

As I proceed into my post-middle age years, I begin to feel like the monumental bronze monuments I adore. I am experiencing “the creep.” The settling and spreading of age is apparent as my weight bears down and I begin to bow and bulge. I often contemplate what will mark my existence when I am gone. I am sorry I cannot order a Monumental Bronze marker for myself. I would dearly love a unique artifact from the city of my birth that I could have cast and assembled to my taste to mark the last place on earth for me.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bridgeport History Center, Bridgeport Public Library, Burroughs-Saden Building, 925 Broad Street, Bridgeport, CT, https://bportlibrary.org/hc/

Connecticut’s Civil War Monuments, Stratford, https://chs.org/finding_aides/ransom/117.htm

Gettysburg’s Stone Sentinels, 4th Ohio Volunteer Infantry Regiment, http://gettysburg.stonesentinels.com/union-monuments/ohio/4th-ohio/

Johansen, Lynn, White Bronze, Lulu.com, 2008, Google Books: https://books.google.com/books?id=8VQzEhW1kZ4C&pg=PA14&source=gbs_selected_pages&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

Keister, Douglas, Stories in Stone, A Field Guide to Cemetery Symbolism and Iconography, Gibbs Smith, Publisher, Salt Lake City, 2004

Leskowitz, Frank J. Science Leads the Way: White Bronze Cemetery Monuments, http://gombessa.tripod.com/scienceleadstheway/id8.html , 1995-2020

Monumental Bronze Company Sales Catalog, White bronze monuments, statuary, portrait medallions, busts, statues, and ornamental art work, 1882, Smithsonian Libraries, https://library.si.edu/digital-library/book/whitebronzemonu00monu

Neighbors, Joy, A Grave Interest: White Bronze – A Monument of Quality, 2014, A Grave Interest Blog, http://agraveinterest.blogspot.com/2012/06/white-bronze-monument-of-quality.html

Orcutt, Samuel, Rev, A History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport Connecticut, Part II Press of Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor, New Haven, Connecticut, 1886

Smithsonian Museum Conservation Institute: Zinc Sculpture, https://www.si.edu/mci/index.html

The Washington Post, Why Those Confederate Soldier Statues Look a Lot Like Their Union Counterparts, August 18,2017, https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/why-those-confederate-soldier-statues-look-a-lot-like-their-union-counterparts/2017/08/18/cefcc1bc-8394-11e7-ab27-1a21a8e006ab_story.html