Bridgeport Baseball

By: Michael Bielawa, Baseball Historian

The fields and shoreline of Bridgeport, Connecticut possess a magnificent baseball heritage. Since its inception, “base ball” profoundly impacted the city. In fact, Bridgeport’s social history provides a fascinating microcosm of baseball’s evolution from a regional amateur game to its eventual ascendancy into the national pastime.

The game was fully received in Bridgeport during the closing years of the American Civil War. The year 1865 marks two important symbiotic events in the community’s social fabric, illustrating a rising interest in the outdoors and physical exercise.1

- The Common Council moved to dedicate and improve lands for two public parks, Seaside Park and Washington Park.2

- The birth of serious-minded ball teams.

There was actually a lack of teams calling Bridgeport home prior to 1865. It was more common at this time for local newspapers to list billiard results, horse racing and the only ball game in town – cricket.3

By year’s end, the East Side boasted some of the very first baseball games in Bridgeport. Citizens could watch the Excelsiors and Stars play, but these teenage clubs were strictly “muffin,” or rather, ill-practiced at best. Inter-squad games were also played in the East Side by the American Base Ball Club at their grounds situated just north of Washington Park.4

A big step toward regulation games took form at the end of August 1865 when 98 students and administrators from the local college, Bryant, Stratton & Corbin’s Bridgeport Business College and Telegraphic Institute, gathered to write a constitution and by-laws creating a 30-man base ball club.5 Grounds were secured downtown on the upper part of Beaver Street and the school team voted to follow the rules of the New York game.6

This era also marked the advent of Bridgeport’s most famous baseball player, James O’Rourke (1850-1919). Jim and his brother John played ball in east end fields during the late 1860s and early 1870s. James O’Rourke’s big league career began when he signed with the National Association Middletown Mansfields in 1872.7 A few years later, as a member of the Boston Red Caps, O’Rourke got the first hit in National League history on April 22, 1876. This was one of many “firsts” James would record. His accomplishments on the national level and his contributions to the game in New England led to O’Rourke’s induction into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945.8

Bridgeport’s first professional team were the Giants of the Southern New England League and later the Eastern League.9 Their home grounds were situated within the northern portion of P.T. Barnum’s Winter Headquarters on State Street. Just a few years later, during the late 1880s, an outstanding amateur circuit also took hold in Bridgeport, the Senior City League. Still in existence, this league plays its games at Seaside Park.

Baseball blossomed in the Park City during the opening years of the 20th century. Beyond the popular local professional team, the Orators, Bridgeport’s sprawling industrial base gathered an immigrant population capable of supporting numerous semipro ball clubs.10 A world without automobiles, air-conditioning, television or radio fostered neighborhood socialization on a tremendous scale. Outdoor sports, dictated by the seasons, were readily embraced. Workers playing baseball during their free-time represented places of employment, churches, guilds and social clubs. Recreation, company pride, and team bragging rights prompted factory owners to finance clubs. Bridgeport’s Industrial League, organized in the early 1900s, enticed citizens onto diamonds and into the stands, for half a century.

Want to learn more about Bridgeport Baseball? The Bridgeport History Center has the following materials available:

1. Bridgeport Evening Farmer, March 29, 1866, notes, “Now that the season for all outdoor sports and amusements is approaching, everything is being got in readiness by the various clubs and individuals, lovers of field, turf, and aquatics, to make this year one of unusual interest. Amongst the various outdoor sports, that of Base Ball is becoming by far the most popular, and very properly so, being entirely of American origins.” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, May 26, 1866, states, “Every city, deserving the name, has its public grounds, its breathing places, where the hard-worked and over-worked sons of toil can find pure air, healthy exercise, cheerful scenery, sun and shade, green trees, the fresh earth, blue skies, and sparkling waters… Boston has her Common, Hartford her Park, New Haven her public Greens and Elms, New York her Central Park. These are all the peoples’ grounds, the public parks, open and free to every man women and child…so it will yet be with Washington and the Seaside Parks by the people of Bridgeport.”

2. Numerous articles in the Bridgeport Evening Farmer and Bridgeport Evening Standard during 1865 and 1866 provide excellent coverage of the embryonic stages of these parks. The fine story concerning Washington Park and the origins of the East Side are emphasized in the architectural survey by Charles Brilvitch, Pembroke City Historic District Bridgeport, Connecticut (Connecticut Historic Commission, 1990).

3. Bridgeport’s newspapers and the New York Times report on Bridgeport’s 1857 – 1866 cricket matches. Cricket results are also noted in the weekly baseball newspaper, “The Ball Players Chronicle,” Edited by Henry Chadwick (New York: Thompson & Pearson, 1867).

4. Bridgeport Evening Farmer, August 8, 1865. Maps of Bridgeport help illustrate probable locations of contemporary ball fields; Atlas of New York and Vicitnity, “City of Bridgeport, Fairfield County, Connecticut” (New York: Beers & Soule, 1867) and Bridgeport City Directory Map, 1867.

5. Bridgeport Evening Standard, August 29, 1865.

6. Bridgeport Evening Farmer and Bridgeport Evening Standard, September 1, 1865 and Michael J. Bielawa’s section in The Pioneer Project, edited by Peter Morris (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2011), details this Bridgeport team as well as the game’s earliest appearance in the Park City.

7. A concise history of Connecticut’s first major league club is, David Arcidiacono’s Middletown’s Season in the Sun: The Story of Connecticut’s First Professional Baseball Team (East Hampton, CT: Published by the Author, 1999).

8. For an in depth look at the life and legacy of James O’Rourke see, Michael J. Bielawa, From FarField to Newfield: The Baseball Dream of Orator Jim O’Rourke (Fairfield, CT: Published by the Author, 1999).

9. For a photographic history of the city’s connection to the sport see, Michael J. Bielawa, Bridgeport Baseball (Mount Pleasant, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2003).

10. A wonderful look at Bridgeport’s industrial history can be found in Samuel Orcutt, A History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport, Connecticut, 2 vols. (Bridgeport: Fairfield County Historical Society, 1886) and George Curtis Waldo, Jr., History of Bridgeport and Vicinity (New York: S.J. Clarke Publishing, 1917).

Bridgeport’s UFO Legacy: Men in Black and the Albert K. Bender Story

By Michael J. Bielawa

“One of paranormal history’s most bizarre, worldwide, phenomena traces

its origin directly to downtown Bridgeport.” M. Bielawa

Sci-Fi fans will readily recall the brilliant Twilight Zone episode penned by Rod Sterling, The Monsters Are Due on Maple Street. This television fantasy postulates the frightening results of an Alien visitation and its impact on everyday Americans. However if one is to believe Bridgeport stories, monsters in the form of otherworldly Aliens have already visited Broad Street in downtown Bridgeport. Maybe, just maybe, they are watching still.

One of the earliest, and certainly the most infamous, of Earth’s reported “Men In Black” incidents occurred in bustling Bridgeport. According to ufologists, Men In Black, popularly identified as MIB, are ultra-secret agents associated with the FBI, CIA, or an unnamed covert federal department which seek out and thwart those individuals probing too close to the truth behind UFOs. Some ufologists alarmingly postulate that the MIB are actually not of this Earth.

Albert K. Bender was born in Duryea, Pennsylvania, on June 16, 1921. Bender served in the US Army-Air Force during World War II, from June 8, 1942-October 7, 1943 as a stateside dental technician. After his honorable discharge from active service at Langley Field, Virginia, Bender relocated to Bridgeport with his mother Ellen and step-father Michael Ardolino. The family lived at 784 Broad Street. According to Bender, MIB arrived in Bridgeport during 1953. They appeared at his Broad Street home, just a few hundred yards from the main library.

Albert was employed as chief timekeeper at Acme Shear Co., the world’s largest manufacturer of scissors. The factory was located across the Pequonnock River from downtown at Hicks and Knowlton Streets. Perhaps it was Bender’s sense of humor, but in an ironic salute to his job Bender filled his living space with an assortment of twenty chiming clocks. Every fifteen minutes, half hour and on the hour, 784 Broad Street resounded with the din of bells, bells, bells. But the cacophony of ticking timepieces and alarms were merely a small part of Bender’s eccentricities. The timekeeper enjoyed his privacy living in the attic (and its small connected den) of his step-father’s three-story Broad Street home. At some point when Bender entered his late-20s, Albert adorned his realm with a collection of monstrosities. Faux skulls, shrunken heads, and his own original, outsider art. Should friends stop-over Albert made sure to compliment the atmosphere with unnerving sound effects featuring thunder, sobbing and hissing noises on his record player. Enamored with ghost stories and horror movies, the terror connoisseur claimed his blood flowed with ancestral witchcraft. Fittingly Bender dubbed this attic room his “Chamber of Horrors.”

Albert’s unique appreciation for the supernatural coincided with a rash of well publicized “flying saucer” sightings in the American West during the late 1940s, prompting Bender to form one of America’s nascent UFO organizations. In 1952 the Park City resident organized the International Flying Saucer Bureau. World War I flying ace, and CEO of Eastern Airlines, Eddie Rickenbacker became an honorary member. Albert Einstein declined the invitation. The Bureau’s 600 worldwide members, with Bender as president, were dedicated to furthering the study of these mysterious craft. Its headquarters were located in Albert’s Bridgeport home. One of the group’s most enthusiastic members, Max Krengel, also worked as a timekeeper at Acme Shear; he served as IFSB vice president and assistant director. Krengel lived in Stratford. His home was in one of Lordship’s new Cape Cod style houses along Stratford Road, between Hartland Street and Airway Drive. Shortly after its founding, the IFSB reached out to members around the world through a quarterly journal, Space Review. The newsletter shared stories of UFO sightings and offered theories about the origins of these seemingly inexplicable objects.

No sooner had Bender commenced the IFSB than odd occurrences plagued him in Bridgeport. Ill health, strange phone calls, and telepathic messages hounded the researcher. These events coincidently mirrored an outbreak of UFO sightings over southern Connecticut. In addition, Albert felt as if he was being watched. November 1952, at a local movie theater Bender realized a strange man with glowing eyes observing him; and while walking home along Main Street Albert was shadowed. On a separate occasion late one night on Broad Street Bender reported he was telepathically hypnotized and levitated. But the worst phenomenon was the sickening odor filling his attic. The stench of burning sulphur.

Sequestered in his Broad Street home, Albert blended his UFO research with mental telepathy. To further his experiments, Bender prompted readers of Space Review with an audacious request: memorize and silently recite, on a particular day and time, a form letter penned by Bender. Albert’s goal was to connect with Alien life via the simultaneous thought-projection of hundreds of IFSB members. World Contact Day, or as Bender and the IFSB officially preferred, “C-Day,” commenced at 6 o’clock in the evening (EST) on March 15, 1953. The noble telepathic message opened, “Calling occupants of interplanetary craft! Calling occupants of interplanetary craft that have been observing our planet EARTH. We of IFSB wish to make contact with you. We are your friends…” Just over twenty years later the Canadian progressive rock band, Klaatu, incorporated Bender’s words into a haunting anthem. Musical siblings and New Haven natives, the Carpenters, provided their own version of the Klaatu song. World Contact Day is still observed by UFO enthusiasts every March 15th.

Bender’s message did not go over well. His rooms continued to fill with the smell of sulphur and he was telepathically ordered to cease delving into matters that were not his concern. A yellow mist gathered in the attic. Undeterred, Bender announced that the July issue of Space Review would hold a “startling revelation.” It never appeared in print.

In July 1953 Albert Bender was visited at his home by three men. Bender stated “All of them were dressed in black clothes. They looked like clergymen but wore hats similar to [the]Homburg style.” The notorious Men In Black, always in threes, made it clear to Bender that he was to immediately halt all UFO work. They communicated telepathically: “Stop publishing.” Before departing, the MIB confiscated copies of Space Review and in their wake a yellow fog materialized in the upstairs rooms of 784 Broad Street. Again, the vile odor of sulphur wafted through the attic. Unnerved by their other-worldly presence Albert shuddered that he was “scared to death” and was unable to eat for days. The 32 year-old timekeeper would be the recipient of repeated MIB visits.

Not surprisingly, Bender’s paranormal experiences were reported in local newspapers. What might seem borrowed from the plot of a late-night horror movie, Bender’s odyssey can easily be retraced at one of his familiar haunts: the downtown Bridgeport Public Library (Bender prominently notes BPL in his autobiographical encounter with MIB, Flying Saucers and the Three Men (London, England: Neville Spearman, 1962) that he conducted research into the paranormal at the main library; page 14). Bender’s account of the threats from the Men In Black become evident when viewing old microfilmed pages of the Bridgeport Sunday Herald. One Herald article reported the story under the headline, “Mystery Visitors Halt Research” (Bridgeport Herald, November 29, 1953). Bender is quoted that three men in dark suits “flashed credentials showing them to be representatives of [a]‘higher authority’ ” and they asked numerous questions about the IFSB. The Herald reporter, Lem M’Collum, interpreted these visitors as “government” officials. It was only years later when the passage of time apparently lessened his anxiety that Bender explained that the MIB were not of Earth.

The telepathic messages, headaches, his being stalked, and of course the surreal warnings by authoritarians in black suits, compelled Albert to shut down the International Flying Saucer Bureau. A year and a half after founding the IFSB the final issue of Space Review was released in October, 1953. It included a cryptic message, and warning: “The mystery of the flying saucers is no longer a mystery. The source is already known but any information about this is being withheld by orders from a higher source. We would like to print the full story in Space Review but because of the nature of the information we have been advised in the negative. We advise those engaged in saucer work to be very cautious.”

In 1956, fellow IFSB member, Gray Barker penned the book, They Knew Too Much About Flying Saucers. In these pages, Barker detailed Albert’s Bridgeport experiences and introduced the world to the evocatively menacing phrase, “Men In Black.” A decade after his own brush with Aliens, Bender chronicled his strange personal story in a bizarre expose entitled, Flying Saucers and the Three Men. Albert stressed how the dark-suited visitors were mind-manipulating silencers.

Abandoning his forays into the supernatural and UFO research Albert Bender departed Bridgeport and relocated to California three years after publishing his autobiography. Albert Bender passed away, at the age of 94, on March 29, 2016.

Sadly, the house at 784 Broad Street no longer stands. This home where Alien theorists believe beings from outer space made their presence known needed to make room for a different sort of invasion. Urban renewal. Bender’s home suddenly vanishes from city directories in 1957. Its proximity to the brand-new, federally constructed, Connecticut Thruway claimed Albert’s residence (the majority of I-95 was built from 1954 through 1957). Afterward the State Street Redevelopment Project (roughly 1962-1968) razed practically everything (except the Bridgeport Public Library building) south of State Street, between Main Street west to Lafayette Boulevard and down to the thruway –in other words, Albert Bender’s neighborhood. During 1967 the Southern Connecticut Gas Company’s parking lot absorbed a swath of Broad Street, including the former backyard of the “Chamber of Horrors.” Bender’s portal to the Beyond was forever closed. Was it just a coincidence that the government bulldozed Bender’s residence? For those conspiracy-minded readers one could choose to suspend disbelief and mull over the possibility that this urban destruction was part of a vast government plot. It’s fascinating to ponder, even from a sci-fi perspective, that all evidence of the MIB and Bender were eliminated from the Bridgeport streetscape. (Just don’t tell anyone I mentioned it.)

What, if anything, really transpired within the walls of 784 Broad Street? Could events be explained by Albert Bender’s mental state? Was the Bridgeport resident hallucinating? Did the stress of managing an international organization, and publishing the Space Review, generate a sense of paranoia and trigger a nervous breakdown? Some might say Bender’s experiments opened a door to an Occult force. Others shudder at the thought of demons. Or, as ufologists avow, it really was Aliens. Take your earthbound, or celestial, pick.

Whether the MIB arrived from Washington, D.C., were born of Albert Bender’s imagination or were transported here by Alien science, one of paranormal history’s most bizarre, worldwide, phenomena traces its origin directly to downtown Bridgeport. It would be appropriate to commemorate Bender’s legacy with an historical-folklore marker at the site of 784 Broad Street. To borrow, and retool, an observation made by the Nobel Prize winning Danish physicist, Niels Bohr, “Anyone who is not shocked by what happened in Bridgeport has not understood what happened in Bridgeport.” Of course, Bohr was commenting on quantum theory, but his words could readily apply to a different subject of scientific inquiry… namely, who, or rather, what, may have visited Bridgeport. Only Albert Bender knows. Now he is silent.

###

Bridgeport History Center Sources

- Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps (location of Albert Bender’s home)

- Bridgeport City Directories (Bender’s home address and residents in household)

- Bridgeport Post and Bridgeport Herald (local, contemporary, news coverage about Bender and the Men In Black)

- “Albert Bender to Wed Betty Rose Saturday”, Bridgeport Post. October 13, 1954.

- “Barker Forging Ahead”, Bridgeport Herald, January 25, 1959 and Bridgeport Sunday Herald Magazine, February 1-5, 1959.

- Beckwith, Ethel. “Don’t Be Afraid, Darling; It’s Bender”, Bridgeport Herald. May 25, 1952.

- “Bender Gave Up Work”, Bridgeport Herald, January 25, 1959 and Bridgeport Sunday Herald Magazine. February 1-5, 1959. (Bender later stated that this article ran without his permission or endorsement, Flying Saucers and the Three Men, page 172.

- Husar, Ruth. “A. K. Bender Authors Book On Flying Saucer Insight”, Bridgeport Post. July 11, 1962.

- M’Collum, Lem. “Mystery Visitors Halt Research: Saucerers Here Ordered to Quit,” Bridgeport Herald. November 29, 1953. (Bender later stated that this was an unauthorized article and that he did not provide any information to the reporter; Bender explains that this article is “filled with errors and exaggerations,” Flying Saucers and the Three Men, page 151.)

- “Silenced Because They Knew Too Much About Flying Saucers”, Bridgeport Sunday Herald Magazine. February 1-5, 1959.

- “Terror in the Skies: Fabulous Book Unveils Saucers, Messengers”, Bridgeport Herald, January 25, 1959 (reprinted as “Silenced Because They Knew Too Much About Flying Saucers”, Bridgeport Sunday Herald Magazine. February 1-5, 1959). Bender later stated that this article ran without his permission or endorsement, Flying Saucers and the Three Men, page 172.

- “What’s Saucer for the Goose Is Flying Saucer for the Gander”, Bridgeport Sunday Herald Magazine. February 1-5, 1959.

- AncestryLibrary (Proquest) (data on where Bender and his family lived and their vital statistics)

- Aerial Survey Maps (through the Connecticut State Library)

- Bender, Albert. Flying Saucers and the Three Men (BPL Rare Book)

- Palmquist, David W. Bridgeport: A Pictorial History (Norfolk: VA, Donning Company, 1981) (information concerning downtown’s razing and the State Street Redevelopment Project)

- Bridgeport History Center Newspaper Clippings Files:

- “INDUSTRIES — Acme United Corp (originally Acme Shear Co.).” (Company history. Albert Bender served as the timekeeper for Acme Shear Company)

- BRIDGEPORT, CITY OF–Redevelopment Agency

Civil War College Baseball & Those Fabulous Jones Boys

By Michael J. Bielawa

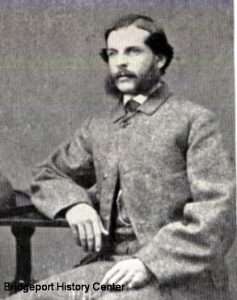

photo: Seth Jones 1863

Most fans in tune with collegate baseball’s heritage are familiar with the College World Series played each June in Omaha. Many may discuss outstanding programs at Louisiana State University, USC or Arizona State. As for historic college ball, New Englanders have inherited storied Ivy League grandstands filled with cranks tossing straw hats high in the air to cheer nines from Yale or Harvard or Brown. However, the contributions of college baseball in Bridgeport have long been neglected. In reality, college baseball had a tremendous impact on Bridgeport playing fields during the game’s primordial era.

The city’s college baseball lineage dates back to those months immediately following the close of the American Civil War. The Bryant, Stratton & Corbin’s Bridgeport Business College and Telegraphic Institute College was located downtown, situated in rooms above the post office. The school was a member of a national chain of mercantile colleges founded in Cleveland in 1854. Here in Bridgeport, Professor A. Corbin, Jr. oversaw classes advertised for “Young Men, Boys, Men of middle age, and ladies desiring to act as Book-keepers, Accountants, Salesmen, Agents, or wishing to perfect themselves as Teachers of Penmanship, or to engage in active business of any kind.”

On August 28, 1865, ninety-eight students and administrators from the Bridgeport institution gathered to write a constitution and by-laws creating a thirty-man base ball club. Professor Corbin was elected president of the “Business College Base Ball Club of Bridgeport.” Grounds were secured downtown, on the upper part of Beaver Street, and the school team voted to follow the rules of the New York game Professor Corbin graciously distributed copies of 1865 regulations. Practice days were selected to take place Mondays and Wednesdays, from five to six o’clock in the afternoon, and Saturday mornings at eight.

Across the Pequonnock River, in East Bridgeport, the recently organized American ball club had been playing scrimmages against first and second nines of their own club. Now the East Bridgeport club had the opportunity to take the field against this new downtown college team.

Five months after the founding of the Bridgeport college club, at the end of January 1866, Professor Corbin was succeeded by his assistant Seth Benjamin Jones, Jr. Jones is a pivotal figure in the city’s baseball landscape. Born in Bridgeport on July 3, 1841, he attended Williams College in northwestern Massachusetts where he was a member of the school’s vaunted Greylock Baseball Club. Following graduation in 1863 Jones taught for two years in Bennington, Vermont before coming home to a job at the Bryant, Stratton & Corbin’s Bridgeport Business College (Seth would continue to exert a potent impact on the city’s education system by founding the long lived Park Avenue Institute in 1871.)

At the helm of the business college Seth shared his knowledge and enthusiasm for sports with his Bridgeport students. Jones expanded the team’s community appeal when he helped reorganize the club on May 30, 1866. On that date the college team was renamed the Bridgeport Club and the roster was no longer restricted to students. In addition, home grounds were moved to the foot of Warren Street nearer to the new Seaside Park.

Seth Jr., who played first and third base, along with his siblings, became the prime force behind the Bridgeport Club. The Jones family resided on Union Street, in downtown, with their father Seth Jones Sr., an early Bridgeport entrepreneur. Daniel Jones, a club director, was a captain of one of the school’s various nines, he played left field as well as second and third base; Nathaniel, was stationed in center field; and William, the club president, was the team’s catcher. William H. Jones, born about 1845, was a partner in the Lyman & Jones agricultural warehouse located next to his brother Seth’s business college. Nathaniel H. Jones, born in 1839, was later a teammate of future Hall of Famer, James O’Rourke, on the 1871 state champion Osceola Club.

As notoriety of the Bridgeport Club grew, the Yale Base Ball team decided to challenge the Park City’s most prominent nine. Yale’s ballists were cordially received at the train depot by the Bridgeport Club on Saturday October 20, 1866, and escorted to a ball field at the old State Fair Grounds. This ball yard was located on a farm owned by Deacon David Sherwood, just beyond the city line in neighboring Fairfield. The area had been utilized nine years earlier, in 1857, by the Connecticut State Agricultural Society to highlight the state’s farming.

The well-attended game was the Bridgeport team’s first baseball match against Yale, an event that would be repeated several times over the next 18 months. Yale handily won the initial contest by a score of 58 to 10 and then departed for their ivy halls on the five o’clock train.

As the season came to a close William H. Jones and Stephen M. Cate Jr. were selected to represent the Bridgeport Club at the National Association of Base Ball Players held in New York City, December 12, 1866. Bridgeport baseball was now officially recognized on a national level.

In less than a year and a half after its founding, the dynamic efforts of Bridgeport’s college team had greatly enhanced the area’s sports scene. They represented the first official baseball club in city history (although organized a little earlier, the Americans hailed from across the river and called East Bridgeport home); the college team helped solidify the more modern rules of the New York Game in Bridgeport; the team’s presence provided a means for games to be played beyond inter-squad contests; and by enticing Yale’s nine to visit Bridgeport, local baseball’s influence expanded. As a result, the Bridgeport College Club should rightly be remembered as an important component of mid-Nineteenth century baseball’s establishment in southwestern Connecticut.

Sources:

Bridgeport newspapers, the Bridgeport Evening Standard and the Bridgeport Evening Farmer, illustrate the progress of cricket and baseball, as well articles concerning the Bryant, Stratton & Corbin/Jones College during 1865-1866. Biographical information regarding the Jones family is drawn from United States Census records and newspaper coverage. Seth Jones, Jr.’s college and career in education is set forth in, Williams College Class of 1863, Class of Sixty-Three Williams College Fortieth Year Report, 1863 – 1903 (Boston: Thomas Todd Printer, 1903). The Bridgeport Club’s matches against Yale are listed in local newspapers, “Base Ball at Yale,” in The Yale Literary Magazine, December 1868 and The Ball Players’ Chronicle, October 10, 1867. For information about all of Bridgeport’s parks, including a history of Seaside Park, the History Center at BPL owns extensive files. The first Connecticut State Agricultural Fair was held in 1854. Locales varied year to year and were selected by an executive committee based upon the dollar amounts offered by each bidding city. Bridgeport was chosen to host the fourth annual fair in 1857 (Bridgeport Daily Advertiser and Farmer, April 23, 1857). The grounds were located on “thirty or forty acres” of farmland owned by David Sherwood, a neighbor of P. T. Barnum’s. Once a part of Fairfield this area is now within the boundaries of Bridgeport. Researching 19th century maps and land owners it appears that the approximate locale of the 1857 State Fair was on Fairfield Avenue (running south toward Long Island Sound) near the intersection with Lincoln Avenue (today’s Clinton Avenue). These ball grounds, near the western terminus of the horse railroad, were capable of accommodating a large crowd, perfect for important games.

Did Jack the Ripper Visit Bridgeport? Who Was the Mysterious Fred B. Beleno?

by Michael J. Bielawa

One hundred and thirty years ago this autumn, in 1888, Jack the Ripper terrorized the Whitechapel neighborhood of London, England. The madman brutally murdered five women. Then vanished. Never to be heard from again. Or was he? Some 21st century Ripperologists, as Jack the Ripper investigators are dubbed, think that the unknown assailant journeyed to America. Did Jack the Ripper voyage to Bridgeport, Connecticut? (more…)

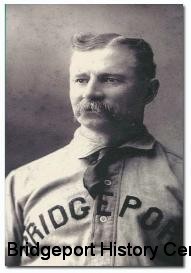

James O’Rourke

Bridgeport’s Scholar-Athlete

James Henry O’Rourke

1850 – 1919

“Orator Jim” O’Rourke, one of the most colorful, popular and accomplished baseball ballplayers of the 19th century was born in East Bridgeport, Connecticut on September 1, 1850. His parents, Hugh and Catherine, had migrated from County Mayo, Ireland, and eventually settled in the section of Bridgeport being developed by P. T. Barnum. Jim attended Waltersville School (where his sister Sarah would one day teach) and Strong’s Military Academy. As a teenager Jim played ball with local clubs, including the Stratford Osceolas, while cultivating a statewide reputation as an outstanding batter. In 1872 Jim joined the Middletown Mansfields, thus becoming a member of America’s first professional baseball league, the National Association. Jim’s father, Hugh, had passed away roughly three years earlier so the twenty-year old ball player refused to leave his widowed mother until the Mansfields’ business manager agreed to hire a farmhand to take Jim’s place. The following season, 1873, O’Rourke became a member of the powerhouse National Association Boston Red Stockings. Jim and his teammates were among baseball’s first international ambassadors, touring Ireland and England with the Philadelphia Athletic Club during 1874. Partly due to Boston’s continued domination of the NA, the National League was formed. The East Bridgeport native made baseball history when he recorded the first hit in the National League, while a member of the Boston Red Caps, on April 22, 1876.

Orator Jim played for a total of 8 major league teams during 23 seasons: Middletown Mansfields (NA), Boston Red Stockings (NA), Boston Red Caps (NL), Providence Grays (NL), Buffalo Bisons (NL), New York Giants (NL), New York Giants (Players League) and the Washington Senators (NL). O’Rourke’s lifetime major league batting average (combining the NA and NL) is .313.

Noted for his ornate language, Jim entertained and confounded teammates, opponents and umpires alike, “Words of great length and thunderous sound simply flowed out of his mouth.” Always an advocate of education, before signing with the New York Giants, O’Rourke negotiated that the club pay his college tuition. Attending classes during the off season Jim graduated from Yale Law School in 1887. Following his major league playing days the Orator attempted a brief stint at umpiring, but the thankless, and often dangerous, role of diamond arbiter was not to Jim’s liking.

Returning to the Park City fulltime, O’Rourke helped organize the Connecticut State League in 1895, serving as league official, team owner, manager, and player. As a direct result Bridgeport retained a professional baseball team for over a third of a century. Proximity to Yale allowed Jim to umpire Ivy League ball games and he also devoted his expertise to consulting baseball hierarchy at the national level. Jim is credited with signing Harry Herbert in 1895, Bridgeport’s first African American to play pro ball. O’Rourke built a minor league stadium, Newfield Park, on his family’s farmland in the city’s East End in 1898. His on field contributions to the national pastime went unabated in Bridgeport for over sixteen seasons. During that time he batted .301 with his team, the Orators. At age 54 Orator Jim caught a complete game, the pennant clincher, for the 1904 New York Giants. He played his final professional game with the New Haven White Wings at age 62. During a stormy winter day, while walking to meet a client, Attorney O’Rourke caught a cold which quickly turned to pneumonia; he died January 8, 1919. Because of his outstanding play, as well as contributions to the game both on and off the field, James Henry O’Rourke was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1945.

Some of James O’Rourke’s Baseball Accomplishments

- Among baseball’s first international ambassadors, 1874

- First hit in the National League, 1876

- Jumping to the Providence Grays with George Wright caused team owners to devise the Reserve Clause, 1879

- Jim and John O’Rourke were the first brothers to play together in a ML outfield, 1880 (In addition to his brother, Jim’s son, James “Queenie,” also played major league baseball)

- First person to play ML ball in four different decades, 1870s, 1880s, 1890s, 1904

- First person to get multiple extra-base hits in a single inning during a World Series game, 1889

- Oldest person to catch a complete ML game

- Home Run Champion of 1874, 1875 and 1880

- Batting Champion of 1884 (.347)

The Ghost of Pembroke Street

One hundred and forty-nine

years old

and Orator Jim O’Rourke

still kneels

on deck

in his turreted Pembroke Street

home

behind windows

dark

muttering

seven syllable adjectives

over his Bridgeport empire

of Jersey barriers

fitted to blockade suburbanite drug trade

on the Park City’s East Side

O’Rourke watches

his Newfield neighborhood

brood

a hobbled ghost too

where no one

plays New England Rules

on the pavement of

his family’s vanished

fields

or cuts a swath

through invisible acres

of corn stalked early October

where he learned Base-Ball and one day refused to sign

until Middletown hired

a farm hand

for his ‘dear ol’ mither’

and waving goodbye

left home twenty-one years old

arriving in the Hall of Fame

on the other side of a forty-six year

train ride

along the Nineteenth century’s

tobacco and whiskey gilded

base lines

in the summers of the Mansfields Red Stockings, Grays

Giants, Bisons

Senators

(gods so old

they’re only box score myths)

O’Rourke got the first National League hit

playing every position

gaining a Yale Law degree

umping, owning

founding

a Connecticut League

those twenty-three years in

The Show

all whittled down

to his one senior citizen at bat

at each Elk’s Club season finale

and the crowd

who every Labor Day

turn out

(once in buggies now in Locomobiles)

to cheer

Bridgeport’s barrister baseballer

their Uncle Jeems

Grand Old Captain of the Game

Orator Jim O’Rourke

steps into the pitch

and shies away

from

the window

his uniform

fading

mingling with the October ruffled curtains

once more

Michael J. Bielawa