Jasper McLevy

It may be surprising to some that Bridgeport operated under Socialist rule for almost a quarter century.

Jasper McLevy had stood on street corners for 20 years railing against the greed of political parties, and voicing what he’d do to make life better during the dog days of the Depression.

In 1933 he got his chance. As both the Democratic and Republican parties were caught up in a series of scandals and financial improprieties, McLevy was elected mayor on the Socialist ticket.

McLevy, however, proved to be more reformer than orthodox Socialist. A roofer by trade and admired by the city’s working class for his honesty and frugality, he introduced a civil service system that cut through the heart of the established parties’ overwhelming patronage practices.

Despite his reputation as a cheapskate, most of the people adored his penny pinching. But McLevy’s critics maintained he could be frugal to a fault. He’d often reject state and federal urban renewal dollars, claiming when the money ran out the city would be stuck with the future maintenance.

He hated spending money unless it was absolutely necessary. The winter of 1938 gave rise to a classic McLevy story.

Snowfall was particularly heavy that year, and the people were not happy with the snowy streets. The Herald, one a popular city newspapers at the time, criticized McLevy and Pete Brewster, his public works director, whom the paper dubbed “Sunshine” because his way of removing snow was waiting for the sun to take care of things.

“Sole responsibility for the terrible condition of Bridgeport streets following last weekend’s double snowstorm rests with Director of Public Works Peter P. ‘Napoleon’ Brewster.” screamed an article’s opening paragraph.

One day, Brewster was sitting in Billy Prince’s, a favorite downtown gin mill, taking a beating from Herald reporters, who needled him with questions like, “How could you allow so much time to pass before ordering plows to hit the streets?” The headlines, name-calling and teasing inched Brewster to the boiling point. Finally, he snapped: “Let the guy who put the snow there take it away!”

That gave birth to the erroneous McLevy quote, “God put the snow there; let him take it away.” It’s as much a part of Bridgeport lore as P.T. Barnum’s supposed saying “There’s a sucker born every minute.” Both men are most famous for lines they never uttered.

Election year after election year, Mclevy triumphed, until Sam Tedesco, a relatively young lawyer and Democrat, challenged him in 1955. McLevy was in his 70s at the time and he had outlived much of his voter base. Newer voters saw the Socialist as out of touch. McLevy was defeated by Tedesco in 1957.

Today, McLevy’s legacy is as Bridgeport’s longest-serving mayor, and as the mayor too cheap to plow the streets.

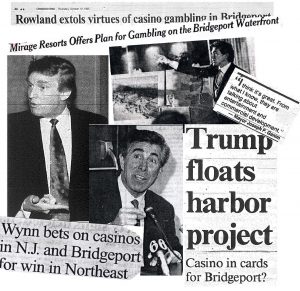

The Gaming Battle In Bridgeport – Then and Now

By Lennie Grimaldi

Donald Trump placed his right hand on the shoulder of a model – tall, blonde, striking, must have been 22 – and with his left hand steered Joe Ganim by the shoulder, easing the two together. “Let me introduce you to a friend of mine,” Trump cooed above the noise at a party for ABC soap stars in Trump’s Plaza hotel, inching her close to the mayor of Bridgeport. “You see this man?” Trump asked. “He’s the most powerful man in Connecticut.” “Oh, really, how powerful are you?” she shimmered. “And do you dance?” Not on this night. On this night, Donald Trump, who early that summer of 1994 announced plans to build a massive theme park along Bridgeport’s impressive waterfront, was courting Joe Ganim.

The mayor of Bridgeport had a tricky balancing act. Connecticut’s General Assembly was debating a bill to expand legalized gambling in the state beyond the popular Foxwoods Casino operated by the Mashantucket Pequot Nation. The driving force behind the legislation was Trump’s chief gaming rival, Steve Wynn, he of the neon, volcanic eruptions, white tigers and rain forests of the swanky Mirage Resorts in Las Vegas. Wynn had already spent millions in Connecticut pushing the gaming agenda on lobbyists, lawyers, advertising buys and community rallies; schmoozing and boozing, wining and dining legislators, offering junkets to Las Vegas and spreading goodwill about what he would do for Connecticut’s tired economy. In August 1994, Ganim was not only mayor of the likely city to host a casino, he was also the Democratic candidate for lieutenant governor and an extremely influential player in the casino sweepstakes.

All this casino talk had Bridgeport buzzing. Connecticut was just hours from Atlantic City, NJ where Trump owned three casinos. Whatever happened in Connecticut would unquestionably impact Trump’s interests in Atlantic City. Just 50 miles from New York City, a Bridgeport casino could reverse the flow of gamblers from the lucrative New York market and entice slot enthusiasts from the Fairfield County gold coast.

A gaming operation in southern Connecticut that Trump did not control would devastate his Atlantic City business. From Trump’s perspective, not only was Atlantic City not big enough for him and Wynn, neither was the tri-state area that included New York and Connecticut. In fact, if Trump could figure a way, he’d drive Wynn from the Nevada desert across California and into the Pacific. Ganim was rightly suspicious of Trump’s overture to the city. Did Trump really want to do a theme park in the city, or did he just want to tie up property so Wynn couldn’t get it?

Joe Ganim knew a good invitation when he got one, and dinner with the Donald certainly sounded tasty. So when Ganim asked me to tag along to Manhattan that day in August, I was game. The night began in the Oak Room, Trump’s restaurant in the Plaza Hotel, the symbol of luxury in Donald’s trophy empire that he bought during the real estate boom of the 1980s for a cool $400 million in borrowed money. The Plaza Hotel’s rich history and French Renaissance architecture was awe-inspiring. Overlooking Central Park south at 59th Street and 5th Avenue, the Plaza was a haven for the well-heeled and high-heeled including the likes of Alfred Gwynne Vanderbilt who was the first to sign the guest register when the landmark opened for business in 1907. Even in the Oak Room, where wealth, fame and power dominate, diners paused momentarily to catch a good look at Donald, as much rock star as developer. We all shook hands, and then Donald said, “Hey, we don’t have to eat here. There are a few parties we could go to. We’ll talk business and pick along the way. C’mon, ABC is throwing a party for their soap stars around the corner, let’s go.”

In step, we followed Donald, cutting a swath through the lavish corridors of Trump’s hotel to a Plaza party room where a bunch of pretty people, soap stars and supermodels drove carrot sticks into dips, popped bubbly, chatted about their daytime dramas and danced to the music of a live pop band. “This is the place to be. It’s incredible, isn’t it?” Donald crowed. We looked at him with polite approval.

“Okay, there’s a party for the Wilhelmina modeling girls at a club down the street,” Trump said. “Let’s go there.” Trump’s limo driver motored down 5th Avenue and Donald waxed expansively about some of his properties. The Plaza, the Empire State Building, his massive West Side Highway project, the this and the that. As we spilled out of the limo a camera crew from Germany at the entrance to the club spotted Donald and threw a spotlight on him. Trump never missed a beat. “They love me in Germany, they love me in New York and they love me in Bridgeport!”

The club was dark, mobbed, beered up and loud. On a small stage some lovely Wilhelmina models were doing their thing. They had long legs and skirts that if they’d been any shorter would have been belts. A thumping crowd hooted and cheered them on, a purplish haze floated around the ceiling lights. Even in the bedlam, everyone recognized Donald. He was like a movie star crashing a nightclub. Towering over the short mayor in size, but not in prestige, Trump shouted through the buzz, “You’ll never have this kind of fun with Wynn!”

Joe Ganim, who owned a superior scent for b.s., knew a master was playing him, but he didn’t care. Ganim loves fun. On the drive home, he said, “This is the kind of thing you could tell your friends, ‘Hey, I went bar crawling with Donald Trump the other night.’”

Trump had purchased a tract of land at the edge of the city’s Downtown and South End that was once the home of the Jenkins Valve factory.

“If expanded gaming is going to happen in Bridgeport, I want it,” he would say. “If I can’t have it, I want to kill it.”

As Trump realized a gaming enterprise in Connecticut was not in the cards for him, he unleashed his lobbyists and lawyers to stop anyone else from getting in on the action, especially his archenemy Wynn.

Local entrepreneur Robert Zeff, owner of the Bridgeport Jai Alai fronton on the East Side, had a particular stake in the gaming legislation. He had secured state approval to transform jai alai into a greyhound track with the hope of installing hundreds of slot machines in his pari-mutuel facility. Zeff was Wynn’s local entrée, working to approve the gaming as furiously as Trump fought it.

Also in the mix was the Mashantucket Pequot Nation, operator of Foxwoods in eastern Connecticut. Lowell Weicker, as governor, had signed a compact with the tribal nation that provided 25 percent of the slot revenue to the state in exchange for gaming exclusivity. A gaming enterprise that the tribal nation did not control in Connecticut could violate the gaming compact and ultimately the flow of dollars to the state. As a result, the newly elected Governor John Rowland, who assumed office in January 1995, rolled the dice on a new gaming enterprise with the tribal nation as lead gaming operator for a proposed East Side/East End location along the designated Steel Point redevelopment area.

In a non-binding referendum in March of 1994, city voters overwhelmingly approved a legislative vote on the issue. Both Wynn and the Mashantuckets spent millions lobbying the state legislature for approval while Trump did his part to torpedo the gaming bill in a move to protect his Atlantic City interests.

Opponents to the gaming bill had significant legislative support, particularly from lower Fairfield County legislators, who cited traffic congestion, health issues and gambling addiction as reasons enough to derail the bill. In the end, the new governor could not persuade his own Republican legislative base to back gaming in Bridgeport. The State Senate voted down the bill.

The city experienced a gaming hangover.

Uncertain what to do with the five acre parcel he owned in the city Trump lost interest in paying the roughly $300,000 a year in property taxes.

In the spring of 1997 Trump fired off a letter to Ganim griping about the injustice of having to pay an extravagant tax bill for an industrial eyesore. Trump deeded the property to the city in exchange for waving the back taxes. The property became home to the Bridgeport Bluefish professional baseball team where a minor league baseball stadium was built.

Fast forward to September 2017. Declaring MGM Bridgeport can be “a major economic force, a top-tier entertainment resort, and an essential contributor to this community,” MGM Chairman and Chief Executive Officer Jim Murren, a Bridgeport native, shared details of a $675 million waterfront resort for the East End creating thousands of construction and permanent jobs, a guarantee $8 million annually to the city as the host community in addition to millions more from real estate and personal property and building permits. MGM Resorts International partnered with the RCI Group, developers of Steelpointe Harbor, to build a casino on the old Carpenter Technology site on Seaview Avenue.

The proposal requires state legislative support because of a gaming monopoly the state granted Connecticut’s two tribal nations in exchange for 25 percent of the slot take, a number MGM officials assert is dwindling, with a promise of more revenue to the state including an up-front $50 million licensing fee upon a green light. MGM has given state officials swimming in red ink something to think about as legislators try to settle on a state budget. MGM pegs its revenue stream to the state at more than $300 million annually.

Noting the state’s bleak fiscal picture and the battle ahead in the state legislature with the tribal nations that run Mohegan Sun and Foxwoods protecting their turf, Murren added “this project can help to turn the economic tide of this state. We just need the political commitment to make it happen.”

MGM says the community benefits include:

– More than 7,000 new jobs in the Bridgeport area

– $50 million in license fees paid to the State of Connecticut in fiscal year 2018

– $8 million in annual payments to Bridgeport (as host city, in addition to taxes payments)

– $4.5 million in annual payments to surrounding communities

– More than $600 million in new private investment; 100% privately financed construction

– $430 Million in new labor income

And right out of the box Bridgeport received the blessing for this project from New Haven officials including Mayor Toni Harp, sitting next to Mayor Joe Ganim at the news announcement. New Haven will host MGM’s work force development and training center extending the economic impact to the Elm City. Embracing the proposal Harp told the gathering overlooking Yellow Mill Channel and the harbor, with a nod to her former peers in the state legislature, “Don’t shoot ourselves in the foot.”

What makes this proposal different than other casinos swelling around Connecticut? Murren and MGM official Uri Clinton argue proximity, a New York and Fairfield County market, waterfront views and amenities like no other casino in the state. “We are the market leader,” said Murren. “We are doing as well today as 15 years ago.”

Murren also spoke on a personal level about his roots in the city where his dad owned a saloon on State Street. His mother resides in the city’s North End. “We’re the right developer, the right time, the right place.”

MGM Bridgeport calls for 2,000 slot machines, 160 table games, a 700-seat theater, 300-room hotel, retail and multiple dining options.

On some level a proposed gaming established is surreal for the city. Joe Ganim is back as mayor and Donald Trump is president.

But still the question remains, will it receive legislative approval?

(Lennie Grimaldi, author of Only In Bridgeport: An Illustrated History of the Park City, served as a media consultant to Donald Trump, as well as political advisor to Joe Ganim in the 1990s. His observations come from a first-hand view of gaming machinations in the city and state.)

The Bridgeport History Center has a large collection of newspaper articles on gambling and casinos in Bridgeport that date from 1980-2000+