A Witch Hanged in Bridgeport

A Witch Hanged in Bridgeport

By Eric D. Lehman

In the middle of the 17th century, Bridgeport was simply a no-man’s land between the growing colonial villages of Stratford and Fairfield. That is no doubt why the citizens of these Puritan communities decided to hang a witch here. (more…)

Alfred Fones, Irene Newman, and the Dental Hygiene Revolution

The idea of going to the dentist to get your teeth cleaned, before they rotted away, took shape in Bridgeport, thanks, in part, to the son of the city’s mayor.

Civilion Fones served as mayor in 1886 and 1887, and knew P.T. Barnum well. He was also a practicing dentist, and the first “dental commissioner” of the city.

His son, Alfred, born in 1869, followed in his footsteps. When he became a dentist at the turn of the twentieth century, people primarily came to him to get their rotten teeth pulled. But through his work, and the work of his cousin Irene Newman, the idea of dental hygiene was born.

The year Fones graduated dental school, it was discovered that bacteria caused tooth decay. Dentists across the country came up with various ideas to combat that, including something called “Odontocure,” in which a woman with an orange wooden stick, pumice, and a flannel rag patrolled the neighborhood cleaning teeth. Most gave up, having no time in their busy schedule of yanking and pulling to actually clean the teeth. But Dr. Fones had another idea. He trained his cousin and chair-side assistant, Irene Newman, to do this delicate work.

In 1907 Newman first performed the duties of what Fones called a “dental hygienist” at their offices on Washington Street in Bridgeport. Although many thought this practice crazy, scoffing at the idea that people would go to the dentist regularly to have their teeth cleaned, others supported it. This led Fones to a further idea: opening a school.

By 1913, Fones and Newman were instructing the first class of “dental hygienists,” creating teaching aids like those used today. People from as far away as Japan traveled to their carriage house basement clinic in Bridgeport. They also instituted a program in the schools to teach students about oral hygiene at home.

The state of Connecticut was so impressed, they issued the world’s first license for practicing dental hygiene to Irene Newman. The idea quickly caught on around America, and the world. Due to the hygiene program in place in the city, Bridgeport had the lowest death rate of any large city in the world during the influenza pandemic of 1918.

Dr. Fones went on to help E. Everett Cortright found the Junior College of Connecticut, which later became the University of Bridgeport. Cortright honored his friend when he named the first new academic building Fones Memorial Hall, and of course named the university’s dental hygiene school after this pioneer.

The world’s first dental hygienist, Irene Newman, was asked in 1950 about her part in this saga. Modestly, she said, “I didn’t think a thing of it. The work was there to do, and I did it.”

Want to learn more about Alfred Fones and Irene Newman? The Bridgeport History Center has the following materials available:

— Bridgeport: Tales from the Park City. By Eric D. Lehman (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2009.

— Folder of contemporary newspaper articles on Dr. Fones and Irene Newman.

— Records of the Bridgeport Dental Society

Beardsley Park and Zoo

By Eric D. Lehman

Wealthy cattle baron James W. Beardsley was watching children play outside one day when inspiration struck. He decided they deserved “a place that would always be theirs.”

So, in 1878 he donated to the city more than 100 acres of land at the north end of Bridgeport along the Pequonnock River, on the condition that it “shall accept and keep the same forever as a public park.”

Beardsley Park was born.

In 1881, famed architect Frederick Law Olmsted, who had previously designed the city’s successful Seaside Park, created a plan for a “pastoral” park, using the existing contours of land in what was called “rustic arrangements of boulder and parterre.”

Soon, citizens relaxed on lawns shaded by European beeches and took dips in the wide expanse of Bunnell’s Pond. A replica of William Shakespeare’s home, the “Anne Hathaway Cottage” was built in the park on the 300th anniversary of the author’s death.

In the years in which Barnum and Bailey circus had its winter quarters in Bridgeport, animals like zebras, camels, and elephants were exercised in the park. This heralded the park’s future, and in the year 1920, City Parks Commissioner Wesley Hayes began the process of creating a zoo.

Beginning with exotic birds from local citizens and circus retirees from Barnum and Bailey, the zoo grew quickly.

At first, it was a “drive-through” zoo, where visitors could literally see the exhibits without leaving their cars.

The city invested $50,000 to build a large greenhouse, and some animals stayed in its warm confines during the winter months. Soon, monkeys, leopards, and llamas joined more unusual animals like silver foxes and tree ducks.

In 1997, the Connecticut Zoological Society bought the zoo from the city and runs it as a nonprofit institution. Today, it is still the only zoo in Connecticut, with one of the largest greenhouses and a rare carousel.

Today, Beardsley Park remains a place of refreshment and relaxation for the city’s residents. As designer Frederick Law Olmsted said, it is “just such a countryside as a family of good taste and healthy nature would resort to, if seeking a few hours complete relief from scenes associated with the wear and tear of ordinary town life.”

A statue of James Beardsley by Charles Henry Niehaus was erected in 1909 and remains at the entrance to the park, watching over the land he donated, land that will “always be theirs.”

Want to learn more about Beardsley Park and Zoo? The Bridgeport History Center has the following materials available:

- Bridgeport: Tales from the Park City. By Eric D. Lehman (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2009.)

Connecticut’s Beardsley Zoo: the First Eighty Years, Established 1922, by DeMattia, Robin F. Virginia Beach, VA: The Donning Co. Publishers, 2002.

[590.7 D372c]- Dolly Curtis Interviews: Dr. Howard Hochman, Veternarian for Beardsley Zoo, Bridgeport, CT, 2000 ,

. Easton, CT: Curtis/Cromwell Productions, 2000

- Dolly Curtis Interviews: Greg Dancho – the New Carousel at the Beardsley Zoo ,

. Easton, CT: Dolly Curtis Interviews Television Programs , 1995

- Dolly Curtis Interviews: Greg Dancho – Beardsley Zoological Gardens,

Easton, CT: Curtis/Cromwell Productions, 1994.

- Newspaper Clippings, Bridgeport History Center: “PARKS – Beardsley Park (Zoo)”

- Vertical File, Bridgeport History Center: “PARKS – Beardsley Park (Zoo) and (Carousel)”

- Bridgeport General Photograph Collection, Bridgeport History Center, various images

- Postcard Collection, Bridgeport History Center, various images

- The Story of Bridgeport, by Elsie Nicholas Danenberg; illustrations by Jesse Benton. Bridgeport, Conn.: Bridgeport Centennial, Inc., 1936

- Bridgeport: a Pictorial History, by David W. Palmquist; design by Jamie Backus Raynor. Norfolk, VA: Donning, 1981; 1985

- A History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport, Connecticut, by Rev. Samuel Orcutt; published under the auspices of the Fairfield county historical society. New Haven, CT: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor; published under the auspices of the Fairfield County Historical Society, 1886. 2 v. (viii, 1393 p.): ill., plates, ports., folded maps ; 26 cm.

Notes: Vol. 2 contains also histories of Huntington, Trumbull and Monroe, towns incorporated from old Stratford. Epitaphs from the various cemeteries are included.

Genealogies: v. 2, p. 1113-1358.

[974.691 B85O2]- History of Bridgeport and vicinity, ed. by George C. Waldo, Jr. New York; Chicago: S.J. Clarke Pub., 1917. 2 v., plates: ill., ports. ; 28 cm.

Notes: Vol. 2 contains biographical sketches. Includes one chapter each on the towns of Stratford and Fairfield.

[HC974.691 B85w]Beardsley Zoo Poem

Gray pigeons and squirrels trouble

a leafless suburban street,chattering past gas stations

and forgotten hopes, while gray

people slouch in gloveless poverty,

grime-spattered jalopies clattering

through colorless slop.

But some children remember

that on the pine hill, hidden

from the gray houses live yellow

monkeys, screaming cosmic glee

amidst make-believe jungles,

that down the street live rainbows

of tigers,flamingos,and wolves.

–Eric Lehman

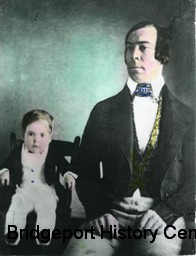

Charles Stratton: Tom Thumb

By Eric D. Lehman

A healthy child of over nine pounds, Charles Stratton was born in 1838 in north Bridgeport to a carpenter and a waitress. However, a faulty pituitary gland kept his growth slow. At age four, he was only twenty-five inches high, and would not grow much more. In the 19th century, the future of someone like Charles might have been bleak. But that year his parents took their son to meet someone who would change his life forever: Phineas T. Barnum.

Barnum saw potential in this small but handsome boy. He taught Charles comedy routines, and soon the student eclipsed the master, with a flair for improvisation. Calling him “General Tom Thumb,” Barnum took Charles on tours of the United States. Curious people flocked to see this “man in miniature,” often expecting to pity him, and being thoroughly surprised by his humor and charm. Eventually, they toured Europe, where Charles’ impersonation of Napoleon became a cultural milestone, imitated for decades by less talented performers. “Tom Thumb’s” command performance for Queen Victoria gave Barnum years of publicity, and made them both very rich.

Charles came back to America, invested in real estate in the growing area of East Bridgeport, and built a house fitted to his unusual size at the north end of town. He even performed at the White House for President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War. Meanwhile, his employer, P.T. Barnum, hired a thirty-two-inch high woman named Lavinia Warren Bump, who had already achieved fame on her own as a performer. Charles fell in love immediately. He brought her on the ferry from New York to show her his wealth and power in Bridgeport. She was impressed, and agreed to be married. The wedding was the event of the year, photographed by Matthew Brady and featured in every magazine and newspaper in the nation.

The newly married couple went on a three-year “working honeymoon” around the world in which they acted their comic and dramatic routines in 587 cities in places like Australia to India. By the time they returned to Bridgeport, Charles Stratton had performed in front of more people than any other human in history before the invention of the television. He had become rich beyond his wildest dreams, happily sailing his yacht in Long Island Sound, breeding thoroughbreds, and meeting the most famous people of his time. This poor Bridgeport kid had taken what many had seen as a disadvantage and turned it into a remarkable achievement.

Many of the artifacts from Charles Stratton’s amazing career can be seen in Bridgeport today at the Barnum Museum.

Want to learn more about Charles Stratton? The Bridgeport History Center has the following materials available:

Bridgeport: Tales from the Park City. By Eric D. Lehman. (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2009.)

General Tom Thumb and his Lady. By Merlie Romaine. (Taunton, MA: William S. Sullwold

Publishing, 1976.)

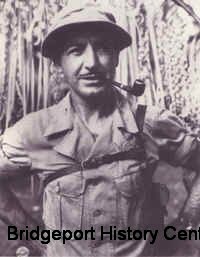

Colonel Henry Mucci, American Hero

Photo: Colonel Henry Mucci

Bridgeporter Henry Mucci was born in 1911 to an Italian immigrant family.

Despite being initially rejected from West Point as “short,” Mucci became a master of physical endurance and hand-to-hand fighting skills. In World War II, Mucci forged a crew of farmers into a dedicated, unstoppable U.S. Ranger battalion, one of the first American special forces units.

When the time came for a daring rescue mission in the Philippines, the military called on Lieutenant Colonel Henry Mucci and his team.

Some 513 survivors from the infamous “Bataan Death March” were scheduled to be killed, and though the move lacked all strategic sense, the Rangers snuck through enemy lines, hustled thirty miles past thousands of Japanese troops, and stormed the prison camp. Only two Rangers died, and every single prisoner was carried back to safety. It was the largest successful rescue mission ever mounted in American history.

In November 1974, the portion of Route 25 between Bridgeport and Newtown was named the Col. Henry A. Mucci Highway. Henry Mucci died in 1997.

Want to learn more about Colonel Henry Mucci? The Bridgeport History Center has the following materials available:

— Bridgeport: Tales from the Park City. By Eric D. Lehman (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2009.)

—Bridgeport at Work, Mary K. Witkowski 2002

— Bridgeport History Center, Newspaper Clipping File, Biography: Mucci, Henry

Related books: Ghost Soldiers. Sides, Hampton. 2001

The Great Raid, movie about Colonel Henry Mucci, 2005.

Merritt Canteen

When the Merritt Parkway first opened all the way to the Housatonic River in 1940, it was immediately considered one of the most beautiful roads in the United States. Horse and buggies, bicycles, and pedestrians were banned; this was a tribute to the new road culture. Six rest areas allowed drivers to fuel up, and many New Yorkers picnicked in the parking lots, glad to be out of the big city. But for those who didn’t bring their own lunch, an alternative was needed.

Local entrepreneur Lorraine Kohn knew this and began serving hot dogs, burgers, and seafood in a small hut at the north end of Main Street, off the Merritt Parkway’s primary Bridgeport exit. By 1958, the “Canteen” was doing well, and Lorraine got rid of the little hut and built a drive-in restaurant, complete with ice cream parlor, patio, and garage-style doors that opened the order windows to the sky. It was the first drive-in style restaurant in the area, and became famous as the road culture of the United States continued to boom. The prices stayed low as others in the Bridgeport area went up, and the unusual fast food joint survived all recessions with apparent ease. In the late 20th century, the Canteen became a destination for nostalgic baby boomers, while appealing to new generations with new menu items.

In the 21st century, the Merritt Canteen now serves a large menu of delicious road food items, continuing to thrive despite all the competition from chain fast food restaurants. Along with classic items like their “brutal dog” – a red hot dog with chili – the Canteen has branched out, serving bison burgers, macaroni and cheese bites, deep fried brownies, and more. Stop by sometime and engage in some culinary historical research.

The Great Fire of 1845

The Great Fire of 1845

When Bridgeport first became its own city in 1836, one of the first orders of business was to regulate the fire-fighting practices of the day. Without a professional fire crew, chaos reigned at every fire, with no one in charge and no one quite sure what to do. The council’s solution was simple; each fireman was required to carry a five foot long white wand as a symbol of authority. No one else was allowed to give orders, but everyone was required to pitch in by hauling water in leather buckets when ordered to do so. And no citizen was allowed to leave the scene until they had permission.

This community organization, as crude as it seems today, helped save the city on December 12, 1845, when the cry of “fire” was heard throughout the downtown area at 1:30 am. George Wells’ oyster saloon on Bank Street had somehow caught ablaze. High winds that night blew the flames to nearby buildings and low tide put the water out of reach of the hoses. Mud from the harbor clogged the pipes in the hand powered fire engines.

The flames quickly spread down Bank Street, over to State Street, and up and down Water Street. Storekeepers tried to save furniture and goods by removing them from buildings in danger. On the wharf, huge barrels of molasses had just been off loaded, and they exploded, sending sticky sugar all over the docks and setting aflame the West India brig that had brought them to Bridgeport.

William Peet’s house on State Street became the keystone, and all efforts were made to stop the fire here by covering the outer walls with water-soaked carpets. This unusual method worked, and prevented the fire from reaching Main Street. People worked together frantically to stop the fire in other directions. William Wall donated crackers and cheese from his grocery to help hungry firemen. Women brought hot pots of coffee from all over town to keep the men awake. By four in the morning, the worst was over, and by day, all the remnants of the terrible fire had been extinguished.

The town took stock and mourned. Forty nine buildings had been destroyed, and forty families had lost everything. Property loss exceeded $150,000, a huge sum at the time, including not only the buildings but an entire lumber yard, 800 barrels of flour, 100 barrels of mackerel, leather goods, cordage, paints, meats, clothing, drugs, shoes, and of course the molasses. The struggling retail community in Bridgeport moved up from the docks to Main Street, and remained centered there for the next hundred years.

There were other fires in Bridgeport in the following decades, including the tragedy at P.T. Barnum’s mansion of Iranistan. In 1877 Bridgeport would face another destructive fire at the Glover hat factory, which would claim the lives of 11 men. But no other fire would destroy such a large swath of the town, nor change the landscape of the city’s growth, the way the fire of 1845 did. Let us hope that remains true in the coming centuries.

The Iron Horse of the Housatonic

The Iron Horse of the Housatonic

By Eric D. Lehman

In 1835, a year before Bridgeport became its own city, a railway along the Housatonic River Valley was planned to connect Stockbridge, Massachusetts with Danbury and Bridgeport. This was an ambitious plan, because most people still distrusted the “iron horse” and its ridiculously fast 15 miles per hour speed.

The private turnpike companies, which controlled most of Connecticut’s transit, protested in every way they could. They lawyered up and even brought out widows and orphans who would supposedly “lose stock” in the soon to be defunct chartered businesses. The Bridgeport and Newtown Company, in existence since 1801, would be particularly hard hit. However, they were fighting against history, and they lost.

The railroad planned to end its run in Bridgeport, even though the nearby town of Stratford was still bigger at the time. Finally, on March 2, 1837, the new town passed a resolution that gave $100,000 to the new railroad company (later increased to $150,000) and secured that outcome. Paying for that promise was trickier, and it caused endless problems for the first two decades of the town’s existence. However, it also helped Bridgeport eventually become an important nexus of business and travel.

By 1840 the section between New Milford and Bridgeport was complete and a celebration was held on the winter day of February 11. Church bells rang, cannon roared, a band played, and the steam engine whistled. Early travelers found themselves having to keep clear of jumping spikes, avoiding sparks that sprayed back into the cars, and trying not to hit their heads when the train hand-braked to a stop.

Nevertheless, trade increased and more trains were added to the line. One was the “Big Milk” which came to Bridgeport from Pittsfield, Massachusetts, taking milk from all the farms of western Connecticut along the way to sell at the markets.

By 1849 another train connected Bridgeport and New York. The one dollar fare seemed steep, but many took this opportunity for easy travel, including showman P.T. Barnum, who shuttled between his businesses in the big city and his home in Bridgeport.

Then, on August 14, 1865, just after the end of the Civil War, disaster occurred on the Housatonic line. Conductor H.L. Plumb found his passenger train blocked by a broken down freight train. While he backed up, another train came up behind him and smashed into him. Ten people died and another twenty were seriously wounded and burned. Harper’s Weekly called it the “Housatonic Railroad Slaughter.”

However, despite this and other accidents, the iron horse was here to stay, shaping the history of Bridgeport in the century to come.

Want to learn more about the Iron Horse? The Bridgeport History Center has the following materials available:

Books:

Bridgeport: Tales from the Park City. Lehman, Eric. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2009.

The Story of Bridgeport 1836-1936. Danenberg, Elsie Nicholas. Bridgeport Centennial, 1936.

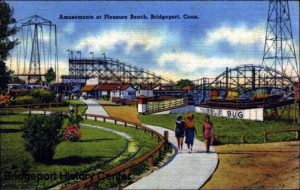

The Legend of Pleasure Beach

By Eric D. Lehman

When the growing city of Bridgeport annexed the borough of West Stratford in 1889, it included a triangular island of thirty-seven acres which would become the stuff of legends in Bridgeport history.

Playing up the legend that Captain Kidd had buried treasure on this barrier island at the mouth of Bridgeport Harbor, liquor dealers J.H. McMahon and P.W. Wren turned the island into an amusement park three years later.

In 1905, the owner of Steeplechase Park on Coney Island in Brooklyn, George C. Tilyou, bought the Bridgeport park, now named Steeplechase Island for the unique ride in which carousel-style horses raced down a metal track.

Two years later, while the Chicago National League team and the Bridgeport team were warming up for a baseball game at the park, a dropped cigarette caused a fire that burned much of the park, including the eponymous “steeplechase” ride.

That gave birth to the island’s first legend: The two teams continued to play five innings as the park burned up, hitting foul balls into the smoldering ruins of the bleachers.

Tilyou sold the park in 1910 and it was renamed Sea Breeze Island. However, attendance was poor and the park closed for several years.

Then, in 1919, the city bought the park, and expanded and improved it. Boardwalks led to a carousel, a roller skating rink, a miniature railroad, a roller coaster, and “The Old Mill” ride that became a popular tunnel of love. The Brickerhoff Ferry brought visitors directly from a dock downtown, and in 1927 a long bridge over a sandy causeway allowed foot and automobile access to what was now called “Pleasure Beach.”

The maple dancing pavilion with bell towers and glass sides became the biggest attraction, featuring the largest ballroom in New England. Stars of the Jazz Age like Gene Krupa, Glenn Miller, and Artie Shaw played here, and thousands of young people flocked to dance on the beautiful maple floor.

A fire in 1953 damaged the roller coaster and a few other rides. Five years later, the amusement park was sold again, but a year later closed for good. The abandoned beer garden later became the home of the Polka Dot Playhouse in 1967. The dance pavilion burned down in 1973, effectively ending the island as a destination.

In 1996 the bridge from the mainland burned, seasonal homes were abandoned, and the Polka Dot Playhouse relocated downtown, renaming itself Playhouse on the Green.

Today, the park has a more unfortunate legendary status: It’s the state’s largest ghost town. The only ones who enjoy amusement at Pleasure Beach are piping plovers. The island is now a protected refuge for endangered birds and plants like the prickly pear cactus.

No one ever found Captain Kidd’s gold, but today the treasure of Pleasure Beach is buried in the memories of Bridgeport’s citizens.

Want to learn more about Pleasure Beach? The Bridgeport History Center has the following materials available:

- Bridgeport: Tales from the Park City. By Eric D. Lehman (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2009.)

- Bridgeport on the Sound, by Mary K. Witkowski and Bruce Williams. Charleston, S.C.:

- Arcadia Publishing, 2001

- Newspaper Clippings, Bridgeport History Center: “PARKS – Pleasure Beach”

- Vertical File, Bridgeport History Center: “PARKS – Pleasure Beach”

- Manuscripts Collection, Bridgeport History Center, various topics

- Bridgeport General Photograph Collection, Bridgeport History Center, various images

- Postcard Collection, Bridgeport History Center, various images

- The Story of Bridgeport, by Elsie Nicholas Danenberg; illustrations by Jesse Benton. Bridgeport, Conn.: Bridgeport Centennial, Inc., 1936

- Bridgeport: a Pictorial History, by David W. Palmquist; design by Jamie Backus Raynor. Norfolk, VA: Donning, 1981; 1985

- A History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport, Connecticut, by Rev. Samuel Orcutt; published under the auspices of the Fairfield county historical society. New Haven, CT: Tuttle, Morehouse & Taylor; published under the auspices of the Fairfield County Historical Society, 1886. 2 v. (viii, 1393 p.): ill., plates, ports., folded maps ; 26 cm.

Notes: Vol. 2 contains also histories of Huntington, Trumbull and Monroe, towns incorporated from old Stratford. Epitaphs from the various cemeteries are included.

Genealogies: v. 2, p. 1113-1358.

[974.691 B85O2]- History of Bridgeport and Vicinity / ed. by George C. Waldo, Jr. New York; Chicago: S.J. Clarke Pub., 1917. 2 v., plates: ill., ports. ; 28 cm.

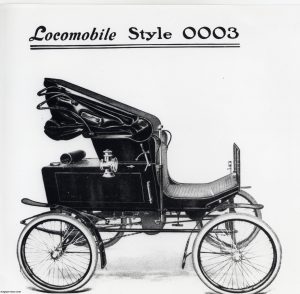

The Locomobile Company of America

In 1899 the Locomobile began as a steam-powered car. With inventor

and electric car manufacturer Andrew Riker’s development of a

new gasoline-powered engine for the company, Locomobile was soon one of the

most popular cars in the world. The “Number 16” car pictured above

won the 1908 Vanderbilt Cup, clocking in at an astonishing 64.38

mph. Locomobile was called the “best built car in America.”

The Bridgeport, CT factory stood on the west side of the harbor, where oil

drums stand today. The factory lay in sight of the famous Seaside Park,

and Locomobile cars were often taken for fast drives on gravel pathways

that had been designed for stately horse drawn carriages.

The Locomobile had the distinction of being the first car not designed to

look like a ‘horse and buggy.’ Andrew Carnegie and Charlie Chaplin took

pride in owning one, and a young Walter Chrysler took apart and put

together a Locomobile to learn about cars. During World War I, the company

sold the Riker Truck to the British army, contributing more vehicles to

the war than any other American company.

The brand became a watchword for quality automobiles, catering

toward a luxury market. Tiffany and Company even supplied the cars’

silver fittings. However, with the increasing use of autos by the

general populace, and the cheap, accessible cars now produced by Ford

Motor Company and GM, Locomobile began to lose importance and customers.

The Great Depression sounded the final death knell for this fabled

Bridgeport car company.

The Planning of Seaside Park

By Eric D. Lehman

Before the Civil War, no one in town gave much thought to the stretch of rocky land between Bridgeport Harbor and Fayerweather Island at the mouth of Black Rock Harbor. Barely good enough for cows, the land remained inaccessible to horse and carriage until the Union soldiers of the Connecticut 17th mustered there before taking the train to the war. Then, the Bridgeport Standard began a series of articles urging the creation of public parks in the rapidly growing town. In 1864, citizens like Nathaniel Wheeler, P.T. Barnum, and Colonel William Noble bought and donated land along the shore to the city.

For the planning of this park, Nathaniel Wheeler turned to the architectural firm of Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted, which planned Central Park in Manhattan and Prospect Park in Brooklyn. By 1867 Olmsted’s firm had finished their plans, which included a seawall, a horse track, and pedestrian walkway, the only “rural marine open space” in the United States. Engineers drained the marshy borders, diked huge sections, and created circular drives and grassy lawns for the pleasure of Bridgeport’s citizens. Olmsted himself described the finished product as “a capital place for a drive or walk…a fine dressy promenade.”

At the time, Bridgeport contained only 15,000 people, but this foresight provided green space as the population multiplied eight times over the next fifty years. Seaside Park became a center of activity for the city, with trotter and sulky racing, “base ball” games, and a merry-go-round for children. P.T. Barnum liked it so much he designed his summer residence, “Marina Park,” to look out on “large lawns, broken only by the [center]grove, single-shaded trees, rock-work, walks, flower-beds, and drives.”

The park quickly became a haven for monuments. In 1876 the Soldiers and Sailors Monument was dedicated to the American war dead. A statue of Elias Howe, inventor of the sewing machine, had been slated for Central Park in Manhattan, but found its way to his home turf of Bridgeport instead. After P.T. Barnum’s death, a bronze statue of him by sculptor Thomas Ball was added on the showman’s favorite spot. Finally, the Perry Memorial Arch was built in 1918, designed by Henry Bacon, who also planned the Lincoln Memorial in D.C. The magnificent arch became a symbol for both the Park and Bridgeport itself.

As the years passed more and more land was donated. Much of the marshland to the west was reclaimed, incorporating Fayerweather Island into the park in 1911. People used the horse track to race their new cars, including the Bridgeport-produced Locomobiles. Today, the 375 acre park is on the National Register of Historic Places, and remains one of the only parks of its kind in the United States, a tribute to the foresight and planning of Bridgeport’s citizens.

Want to learn more about Seaside Park? The Bridgeport History Center has the following materials available:

— Struggles and Triumphs. By P.T. Barnum. (Ed. John G. O’Leary, London: MacGibbon and Kee, 1967.)

— “National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination: Seaside Park”. By Alison Gilchrist. National Park Service. http://pdfhost.focus.nps.gov/docs/NRHP/Text/82004373.pdf. November 1981.

— Bridgeport: Tales from the Park City. By Eric D. Lehman (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2009.

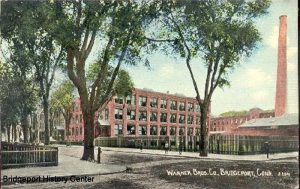

The Warner Brothers and their Amazing Corsets

As doctors in the late 1800s, brothers Dr. Lucien and Ira De Ver Warner became concerned with the use of the corset in women’s fashion. The corset was a piece of underclothing meant to give women an “hourglass” figure desirable at the time. (more…)