A.B.C.D. Cultural Arts Center – a Creative Community Response

By Michelle Black Smith

On July 6, 1970, under the agency leadership of Charles B. Tisdale, the A.B.C.D. Cultural Arts Center (hereafter Art Center) welcomed Bridgeport youth and young adults to explore a variety of creative expression at an office building in downtown Bridgeport. Free of charge and located at 1188 Main Street, the inhabitants of this converted art space were unique tenants among the doctors, lawyers, and dentists who shared the building. The CT Commission on the Arts (hereafter Commission) was established in 1965, the same year that A.B.C.D. received official designation as a regional anti-poverty agency. The timely development of a state commission created to identify organizations capable of providing public art experiences coincided with the development of a community agency determined to offer the citizens of Bridgeport services that went beyond the previous models of targeting the underprivileged. Mr. Tisdale established A.B.C.D. as an agency of programs carefully planned and thoughtfully implemented “…to direct the energies of protest into constructive channels, to transform opportunity denied into opportunity offered, and made real.” A.B.C.D. received a small grant in 1969 from the Commission for a summer pilot program offering daily art classes. Housed at 75 Hurd Ave, and run by Housatonic Community College Art Department Chair Burt Chernow, two hundred children ages 5-18 received instruction at the precursor to the Art Center, with assistance from teens employed by Project Cool.

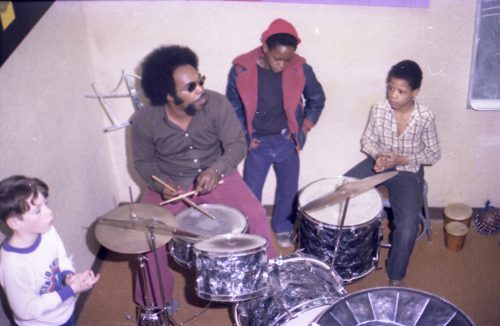

Arts Center Music Instructor Ralph Williams

In 1970, the Art Center received a grant from the Commission that funded a building lease, teachers, and supplies. The program began with Director Ben Johnson and three instructors. The demand for classes at the center, and requests for school site art instruction from the Bridgeport Board of Education resulted in additional funding for more teachers and supplies. The instructors brought with them creative gifts in the visual, performing, and literary arts. Everyone was an artist at the Art Center. Only unfinished homework stood between a student and the day’s menu of creative expression. During the 1970s, the Art Center was one of many free arts organizations active in Bridgeport. The Drama Club, Youthbridge, and the Hall Neighborhood House annual Harambee Festival were a few of the programs available to city youth.

Four years after its start, the Art Center acquired a new home constructed with design input from the instructors to optimize creative spaces. The relocation to the Gary Crooks Memorial Center in the spring of 1974 was bittersweet. The new building, with offices for A.B.C.D., was built to commemorate 8-year-old Gary Crooks, a boy who died on city owned property near the P.T. Barnum public housing projects. Numerous forms of protest demanded justice for the little boy who drowned in a tank unprotected by adequate safety measures. A.B.C.D. Deputy Director Rev. William O. Johnson, P.T. residents, and the Art Center community were at the forefront of a social justice movement that spread throughout the city, demanding that all neighborhoods receive equal services and treatment.

The Art Center was a creative, cultural, social and political space that flourished in the 1970s. It was far more than a place to learn art, photography, and music. The new space had discrete classrooms, large work spaces, a dark room, offices and a kitchen. Drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, music, dance/movement, cooking and movie screenings were just some of the activities offered. A student might go outdoor camping, visit a museum in New York or attend a concert in the park. The move to the Gary Crooks Center increased the attendance of nearby residents, and attracted the interest of adults who wanted to experience what the neighborhood children were doing. Throughout the 70s, the Art Center maintained its character as a vibrant and relevant place for the engagement of arts and ideas.

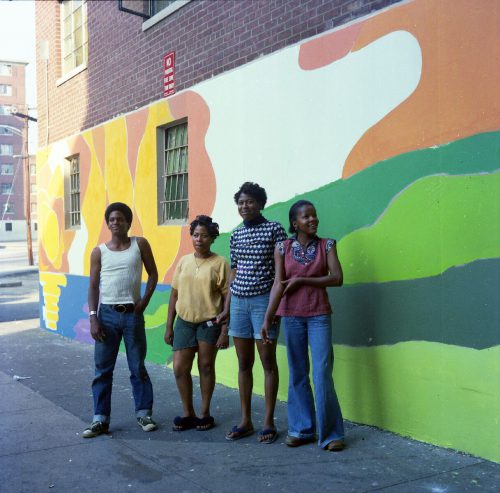

Arts Center students standing by mural

Cyril Lamont Williams was around seven years old on a summer Saturday morning when he accidently discovered the Art Center at its home in the Gary Crooks Memorial Center. Williams, a resident of the P.T. Barnum housing projects, was looking for the summer lunch program he’d attended for the last two years, only to be informed that meals were served on weekdays only. He recollects being met at the door by Wendy Bridgeforth, a visual arts instructor who invited him in to listen to an African drumming lesson. Drumming instructor Ralph Williams (no relation to Cyril Lamont Williams) and soon after piano and percussion instructor Jami Ayinde (Jerry Johnson) influenced, encouraged and taught a boy who would later attend the Berkeley School of Music and become a professional musician. Their influence and guidance extended past the active years of the Art Center. Cyril credits the Art Center with providing a “safe haven” in a neighborhood becoming increasingly dangerous, within a city fighting the detritus that larger cities in the tri-state area could not keep at bay.

The 1980s marked the decline of blue collar prospects, stable incomes, and clear pathways to improve upon the education, employment opportunities and finances of the generation that came before. Like so many cities in America, large and small, the combined effects of disappearing working class jobs and an aggressively growing drug epidemic created a climate of increased poverty, addiction, poor health, failed public education, unsafe areas, and escalation of violent crime. The economics and ills of the 80s hit Bridgeport hard – the Art Center was an early casualty. Severely limited funding, decreased staffing, and a population of young people heading off to colleges and jobs, or gravitating to the supply and demand of crack cocaine turned the Art Center into a shadow of its former self.

The shuttering of the Art Center is both a metaphor for the decline of urban life in the 80s, and an indictment on government’s regard for its city dwelling citizens. Supplies dried up, students stopped attending, and the few remaining instructors reached a point where they could not or would not work without pay. In 1969, the CT Commission on the arts was created to assist and encourage “participation in, and promotion, development, acceptance and appreciation of” the state’s cultural resources. The Art Center answered the Commission’s call, fulfilling all the stated requirements, exceeding expectations, and establishing itself as vital to the Bridgeport community. Approximately 15 years after its brilliant beginning, the Art Center slowly became one more victim in the statistical analysis on the impact drugs, crime, no funding and even less care can have on a vulnerable community. A casualty of shifting priorities and abandoned for a new national ideal, the Art Center lives on in the work created, the photographs that bear witness to shared experiences, and the trajectory of lives affected by both its existence and its demise.

To visit the We Are Artists Every One exhibition virtually, click on the link below:

We Are Artists Every One, the Art Center in Action, 1970-1986