When the Aztec Eagle Began to Soar Over Bridgeport: Part 2 – From “Puebla York”, “Oaxakeepsie” and “Mexchester”

by Abraham Lima

This is Part 2 of a 5 Part Series at the Bridgeport History Center:

The tri-color flag of Mexico, the green red and white. In the middle stands an eagle on a cactus with a snake, the legacy of this eagle, the eagle the Aztecs saw in the middle of the lake with artificial islands they would build soon surrounding the spot. A sign of Huichilopochtli the war god. On it was built Tenochtitlán- or as we say today, Mexico City.

This eagle soars over 2,000 miles away, in Bridgeport, Connecticut, resides the largest Mexican population, both largest foreign born and Mexican descendant population, of any city in New England, ahead of Boston and New Haven. This is her story.

- Part 1 “En El Principio, Los Mojados en USA” and “What are Tortillas?”

- Part 2 – “From Puebla York, Oaxakeepsie and Mexchester

- Part 3 “Men of Maplewood”

- Part 4 – “Miles y Miles Mas (Thousands and Thousands More)”,

- Part 5 – “History of the Future” and “The Eagle Soars”

For Part 1 click below: https://bportlibrary.org/hc/hispanic-populations-and-culture/when-the-aztec-eagle-began-her-soar-over-bridgeport-part-1/

For Part 3 click below:

As the article deals a lot with the New York region and not just Bridgeport, this chapter was divided into subsections to help navigate:

3.1: Origins of “Puebla York” and “Little Quitupan”

3.2: The Carmona family

3.3: From “The City” to Westchester: The Hints Into Mexican Bridgeport from the Region

3.4: The Mexicans of the American Fabrics Company

3.5: Cesar Chavez Visits Bridgeport

3.6 Scattered Records of a Small Mexican Population

3.7: 1982, the Lost Mexican Decade. One Poor Region’s Mass Migration to “Puebla York”:

3.8: “Not Many, But Some”, The Trickle from Puebla York to Bridgeport

3.9: Zaachila and the Diners of “Oaxakeepsie” Origin of a Town’s Community in “Brish-port” 3.10: “Maybe 400”: A Colony in Connecticut

3.11: The Guerrerense Montaña, Tlaxcalan New Haven, and Casa Grande Supermarket

Please Note: This segment, which contains Chapter 3, while on the topic of Mexicans in Bridgeport, will cover with some detail the start of Mexican migration to the places in the region where many of the Mexican community “pioneers” in Greater Bridgeport started off (places like New York City, New Rochelle, Port Chester and Poughkeepsie), which puts into context Bridgeport’s Mexican community within the surrounding region’s still small Mexican population.

Recurring words and information that will appear later in the next chapters are in bold.

New England is the region farthest from the Mexican border in all of the lower 48 states in the USA. Above is a map of the North American landmass showing a land route between South Central Mexico and New England. Source for base maps is Wikimedia Commons, edited by Abraham Lima. Sources: 2020 Census

3. The New Guys in New York and the Spread From Big Apple to Park City (1943*-1990)

How did Bridgeport’s Mexican community arise?

It came about with a few separate chance incidents. A last-minute hitchhike to Manhattan, a visit to a church by a New Rochelle councilman, a Greek diner in Southport, another in Monroe, and some other occurrences.

Origins of “Puebla York” and “Little Quitupan”

Let us briefly go 60 miles southwest from Bridgeport to Manhattan Island. Around the same time the Puerto Ricans were mass migrating to the northeast, in July 1943, Don (ie, Mr.) Pedro Simon and his cousin Fermin were driven by land to New York City from Mexico City by David Montesinos, an Italian-American New Yorker they encountered who vacationed every year in Mexico City, as told in Robert C. Smith’s 2006 book “Mexican New Yorkers”.

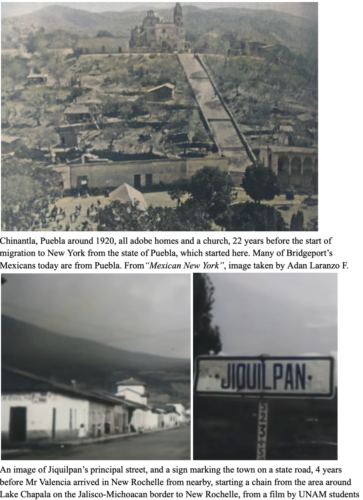

Pedro and Fermin Simon were originally from a rural town in the Mixteca region (made up of southwestern Puebla, northeast Guerrero and northern Oaxaca) the State of Puebla. In the book, the town is referred to by the pseudonym Tucuani. As said in a 1998 New York Times article, the town is Chinantla, Puebla. Migration to the United States from that region started in the bracero program to the southwestern US fields. The two brothers were trying to bribe (the typical method) to get Bracero contracts in strawberry fields in Texas while living in Mexico City but had failed. A friend introduced the brothers to David Montesinos, who was vacationing in Mexico City, and he offered to bring them with him on his way back to New York. In New York City, Montesinos housed them in a Times Square hotel and got them jobs within two days mopping floors at a restaurant. It was D-Day when the brothers agreed to stay for good, rather than go to Texas. The two would begin to invite relatives to New York City.

Pedro Simon’s father had fought in Emiliano Zapata’s army during the Mexican revolution, his New York-born daughter would become a major in the United States Army. He would end up working factory jobs, in restaurants and as a mechanic in New York.

A few years later, in either 1950 or 1952 (sources contradict), Maurilia Arriaga from Chinantla’s neighbor village, Piaxtla, Puebla had migrated to New York to work as the cook for a retired American diplomat, as she had been recommended by her former boss, Mexican actress Maria Felix. Miss Maurilia was what she was nicknamed, and she brought some of her nephews, nieces and friends to New York City.

These 2 events started a migration chain; a few men from these 2 towns in Southwestern Puebla would follow the first few to New York City flying in with tourist visas with the idea to stay and work, inviting relatives and others seeking work, and those relatives or friends would invite another relative, and so forth.

In the mid-1960s, more people from Chinantla, Piaxtla, and from the neighboring towns (towns like Tulcingo, Acatlan de Osorio, Tehuitzingo, or Izucar de Matamoros) would follow and joined them, this time including women, attracted by higher wages and electric conveniences previously unimaginable to them coming from places not yet electrified. With many working in restaurants and textile factories in the 1960s, the weekly wages for these migrants ranged from $50-80 USD ($420-$670 in 2023), much more than back home, causing more migration from these towns.

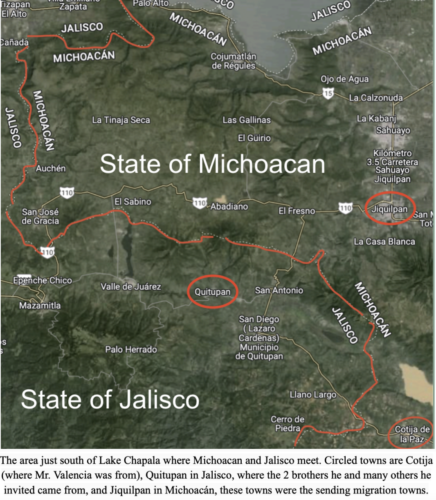

2 years later, in 1954, a city councilman in New Rochelle, New York (in Westchester County) George Vergara, and his wife Allys, visited Mexico City. As Catholics, they visited Sacred Heart Basilica and told the priest they wanted to hire a butler. Antonio Valencia, an ex-seminary student had overheard. Antonio was from a poor family in tiny Cotija, Michoacan, (near the border with the state of Jalisco), and his family later moved to Quitupan, Jalisco nearby. He overheard and agreed to live with them in New Rochelle as a butler. He brought his 6 siblings over in 1955. In 1956, with Mrs, Vergera’s sponsorship, invited 2 brothers from Quitupan, Jalisco to New Rochelle, NY.

They brought friends and relatives from Quitupan and nearby Cotija and Jiquilpan in Michoacan, and they’d bring theirs, eventually totaling hundreds of people. To quote the April 5th 1998 front page special report of the Port Chester Daily Item “They, in turn, brought dozens more friends and relatives from the farming village of Quitupan and neighboring hamlets that border the states of Jalisco and Michoacan in central Mexico. Since then, thousands of Mexicans from the same area have set up tight-knit communities in Mamaroneck, Port Chester, and Mount Vernon.”

Verega had become mayor, and Valencia would look out for the Mexican community and became known by them as the padrino or “godfather” helping them get employment based on their families needs, housing, aiding in court cases, etc. The Mexicans settled in the West To quote a New York Times article from 1992. “Unlike other parts of the New York region where Mexicans come mainly from the Puebla region… in New Rochelle most Mexicans are from the tight cluster of towns in the central-western region where Mr. Valencia grew up.”

The Carmona family:

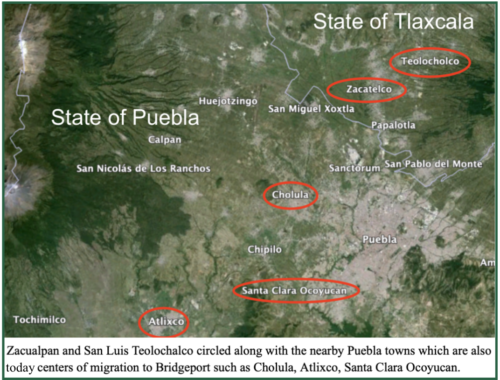

In 1954, the same year Antonio Valencia came to New Rochelle, Guillermo Carmona and his Dominican bride, Rhina Ligia Carmona, settled in Bridgeport on Iranistan Ave. Mr. Carmona was born in 1921 in Tepeaca, Puebla, 8 miles east from the state capital of Puebla City. At age 5 or 6 his family moved to San Pedro Cholula just outside Puebla City in central Puebla, 86 miles north of tiny Chinantla (see map of Puebla above, the map before the last map).

The son of an indigenous Nahuatl-speaking Mexican woman and a white Mexican man, he had an 8th grade education, which was higher than average in 1950s Mexico. He, his friends Heriberto Amaros and another man remembered only by their his daughter, Maria, as “El Gato” (the cat) moved to Bridgeport from New York City. Carmona later moved to Stratford with his wife and two sons, and in 1963 had a daughter, Maria.

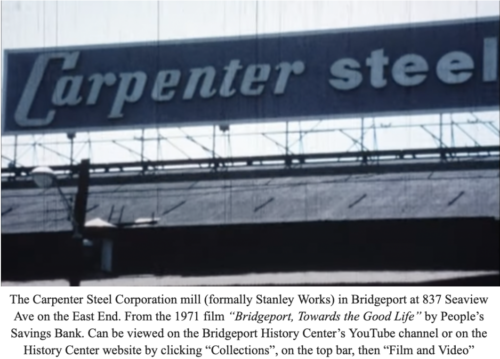

Maria recalls “My dad and mom (a Dominican) moved to Bridgeport in July 1954. They went to Bridgeport because my dad had finally found the type of work he had wanted to find when he first arrived in the U.S. The place was Stanley Works (a steel mill). My father had worked at a foundry in his hometown of Cholula, Puebla and, so, he was a skilled laborer. It took him about 8 years to find that work after living in New York City and working all kinds of jobs, learning English, figuring out how to make his way.” Heriberto also worked at Stanley Works. As a child, Maria would ask her father Guillermo why he came so far from the border and he kept the reason simple and fun. “At first, he told me he decided to go to New York because he had loved listening to music on his shortwave radio. He used to hear shows transmitted from New York. My dad loved jazz music, and he told me that he wanted to go to New York because he was young, single, and wanted to hear jazz played by the great musicians of that time.”

When Maria learned about the Bracero program in high school “I asked my dad about his reason for coming again. He told me he did come during that time, but didn’t apply to be a Bracero. He said he knew he had skills and didn’t want to work in the fields. He also told me that he thought life for Mexicans in California and the Southwest would be difficult based on what he had heard from some people. He figured that if he went further north, he’d be less likely to be treated as badly.”

As an adult, her father told more details about the circumstances behind why left Cholula. “He told me that there had been threats on his life because he had been the president of the local steelworkers’ union at the foundry, and he refused to accept bribes from management. If he took them, he would have been expected to stop asking for certain improvements and just do management’s bidding. He really didn’t want to leave and had resisted for almost a year. When his brother’s life was also threatened, he left to please my grandmother who was very concerned for their safety.”

Maria explained why her father and uncle decided to head to northeastern United States, “El Gato was their friend, and his uncle was a merchant marine. The uncle had been telling El Gato and the men in their family that there was a “big world” outside of Cholula and a lot of work in New York. He said the border was not hard to cross and they should come work there. El Gato told my dad that if he wanted to leave the country, his uncle could probably help him settle in New York. Well, to make a long story short, El Gato decided to join my dad and my uncle, and their friend, Heriberto Amaros, decided to join them.”

“My parents were very Catholic and were surprised that there was no Spanish-language Catholic mass in Bridgeport when they arrived. So, they got together with a few Spanish-speaking [mostly Puerto Rican]friends that they came to know and after a few years succeeded in getting the Diocese of Bridgeport to establish a “mission church” Nuestra Señora de la Divina Providencia” at St. Peter’s Church on Colorado Ave. This became like a home to many Spanish-speaking Catholics in the area. Up to their last years, they would remember the priest who supported their efforts, Monsignor Campagnone. My mom told me how the Diocese resisted establishing a new church catering to Spanish speakers. How someone – I think Monsignor – had suggested proposing it as a “mission,” which proved acceptable. My mom said there were about five or seven couples who committed themselves to growing the community, kind of like “founding families.” Not long after that, Monsignor recommended my mother to work at Catholic Charities in Bridgeport because the needs of the Spanish-speaking Catholic community became apparent, and my mom had secretarial skills and she was fully bilingual.” Mrs. Carmona worked at Nestle in Connecticut, where the Swiss company had its headquarters for the Americas region, and then for General Electric in Manhattan, Fairfield, and Bridgeport.

Maria recalls that “growing up in Stratford, I felt a little different sometimes. Most people equated Latinos with Puerto Rican and Cuban. People often assumed I was one of the two, and only other Latinos knew I was neither. At least I had my Dominican cousins in town with me. Don’t get me wrong, I had friends, but I was very aware that our ways, our food, our manner of being was different from most of my friends. About the only thing our families had in common was being Catholic. But my parents were friendly people, and I know they felt a part of the community. And EVERYONE LOVED MY DAD!!!! He coached baseball, and to this day I hear from people who remember what a great coach he was and also what a great fan he was of the teams my older brother and they played on. He treated kids differently. He assumed they were capable and had patience while they developed skills. And, he stood up to parents when they got a little too critical of their kids. One of his favorite stories was about how he coached one particular team to a championship after rejecting ongoing sideline coaching from one parent. After that, parents didn’t criticize his coaching decisions anymore.”

“Stanley Works eventually became Carpenter Steel, a major employer in Bridgeport. My dad later found work at a manufacturing plant called Thermtrol and then co-owned and supervised a factory himself [Valcan, Inc on Bruce Ave in Stratford near the rail overpass]”.

“I will say that our house was often home for my Mexican relatives who would eventually move to the U.S., but few remained in CT. Most went to NYC or New Jersey.” In terms of her father’s relatives. “My dad’s two other younger brothers came to the U.S. too, and by 1960, the four Carmona men were all in the U.S. My uncles all lived in the same apartment building on Manhattan’s Upper West Side and they all worked in the hotel industry. One of my uncles eventually became the Banquet Manager at the Waldorf Astoria! All three of my uncles went back to Mexico to find wives and those women moved to the U.S. too. My dad also sponsored a couple of my Mexican cousins from Cholula to come live in the U.S.. Most ended up settling in New York or New Jersey for a time before moving to other places like Atlanta, Seattle and Las Vegas. Two of my aunts actually lived in New York and Bridgeport for a couple of years in the early days (in the 50s). One helped take care of my brother while my mom worked. She got her green card at that time (it was so easy to get them back then) and then she moved back to Mexico. The other worked in New York and lived with my uncles, got her green card, and moved back to Mexico. After my grandmother died in 1980, my two aunts moved back to the U.S., and my Tia Chela lived with us in Stratford for quite a while.”

In Mexico’s 1920 census, 55% of Puebla’s population was “pure indigenous”, 40% were “indigenous mixed with white”, and 6% said they were “white”. Puebla then was the second most pure indigenous Mexican state both by population and percentage, after Oaxaca (69% pure indigenous). In Puebla, 28% of the total population spoke an indigenous language in 1920.

Maria recalls “My dad spoke a little Nahuatl but not much. But, my brother Carlos figured out that our Tia Chela spoke a lot of it and that she used to speak it a lot with our grandmother.”

“There were not many Mexicans in Connecticut when I was growing up in the late 60s and early 70’s. In fact, my dad and his Mexican friends would say they were it. If you can believe them, then there were four other Mexican families in all of Connecticut in the late 60s/early 70s!”

Maria said these were the families of two friends in Bridgeport, another friend in Wallingford, and El Gato, who Maria could not remember much about except his name. The Quezada family of Wallingford was made up of José Quezada from Michoacan, his Spaniard wife “Mary” and their daughters. The two friends in Bridgeport were José Solis who was also from Mexico and married to an American woman and Heriberto Amaros, who had married a Portuguese immigrant, Natalia, and had a son.

Carmona recalls that “Every summer for years all the Mexican families got together for a pig roast. I remember our doing one in Beardsley Park one year! Yes, they allowed that back then. Another memory is of the beautiful Indian Wells State Park. We did a few there. And the men would go to a farm to pick out and slaughter a pig! My dad, El Gato and Heriberto all played the guitar and I have very fond memories of hearing these men sing old-style Mexican trio during the evenings of those all afternoon and into the evening pig roasts.”

To get Mexican or Dominican food items “My parents would go to New York City to buy certain food products, but another important way they got food was when family members packed stuff in their luggage when they traveled to Mexico. I had three uncles living in New York and, later, three of their first cousins, and among all of them and my dad, someone was always heading back to Cholula every year, so they brought back what they could. Also, my dad always had what we called his “farm” in our backyard. It was really a garden where in the summer he grew different chiles, tomatoes, and tomatillos for his famous salsa. He’d share his “harvest” with others and even freeze salsa for eating later in the year.”

From “The City” to Westchester: The Hints of Mexican Bridgeport From the Region

In Bridgeport, 24 Mexicans were counted in the 1970 census. Of the 24 Mexican origin people in Bridgeport, 7 were born in Mexico, 17 born in the US with at least 1 Mexican parent. 645 people in Connecticut were of Mexican origin, of which 54 lived in the Bridgeport area (aka; Stratford, Fairfield, Bridgeport, Shelton, Trumbull). Comparatively, by 1972, 15% of Bridgeport’s population, about 25,000, were of Puerto Rican origin, centered around East Main Street. The Immigration Act of 1965 set a limit on Mexican legal immigration, and in 1976, a 20,000 people a year limit for Mexico and all Western Hemisphere countries was enacted. The Bracero workers program ended in 1964, which led to illegal immigration to fill the same jobs by employers.

By 1970, 7,364 Mexicans and Mexican-Americans lived in New York City. Most Poblanos settled in tenements together in dilapidated parts of New York City’s 5 boroughs and Micoacanos and Jaliscienses in the West Side of New Rochelle. Money sent back by these migrants went in part to finance dams, schools, etc in their respective regions, like bringing portable water to Chinantla as well as its first elementary and high school, or various schools in northwestern Michoacán and southwestern Jalisco. In New York, factory owners would help Mexicans get temporary work permits. Single Mexican men often married Puerto Ricans.

“In Port Chester and New Rochelle, it’s mostly people from Michoacán” according to Alejandro (Alex) Lima (formally “Lima-Carrera”), a landscaper and Bridgeport resident since 2005, raised in Tehuixtla, Puebla, a village within Chinantla’s municipality. He was at a government “internado” or boarding school in Champusco, Puebla (just south of Atlixco) on a scholarship when he sent for his parents to the US. He arrived in Port Chester, New York to work in 1968 as a teenager, where his parents and older sisters were already. When he arrived, he had cousins, aunts and uncles living on Market St in Passaic, New Jersey, in Brooklyn, The Bronx and Newburgh, New York. A friend from primary school in Tehuixtla had already bought a house on Liberty Street in Newburgh 2 years before Alex arrived.

According to Alex, in 1968, there were “only 3 Mexican families in Port Chester then, the Fernandez’s, the Carrera’s [his mother’s relatives]and mine, the Lima’s”. When Alex arrived, his father Jasinto already worked in landscaping with Italian-Americans. He had previously been a seasonal bracero in California who was illiterate, but learned math and his signature in night school. His mother Eulalia, born in Piaxtla near Tehuixtla, cleaned offices, homes and worked at a textile factory.

There were no Mexican items, “tortillas weren’t known over here”. Mexican items would not be part of his daily diet again until the 2000s. Alex had to learn Italian from his bosses and co-workers before English.

“New Haven, Port Chester also had a lot of industry. But where there was most was Bridgeport. You could leave one job and have a new one the next day” he said in Spanish. “That’s where they made all the munitions for the Vietnam War!”

He married a Puerto Rican, started a family and worked dishwashing in the Bronx and in local factories before starting landscaping around Greenwich. He also did iron foundry labor in Los Angeles where relatives lived, paper factory work in Stamford, hospital cleaning in White Plains, etc.

Alex said growing up, “There was poverty that you cannot imagine. People didn’t have what to eat… Not us, we always had something to eat even if it was just tortillas and beans, thanks be to God”. As a child he never thought he’d ever have a car, instead he had a favorite donkey named Coca Cola. After a while in the US, Alex bought a Ford Mustang.

In the 1970s, Alex would work in Bridgeport, “sometimes, when they’d called us.”

Asked if he “never met anyone else from Mexico in Bridgeport at the time?”, he said “No. It could be that there were already people in Bridgeport, there were already Mexicans over here” in the region. He had many Puerto Rican friends in Bridgeport at that time.

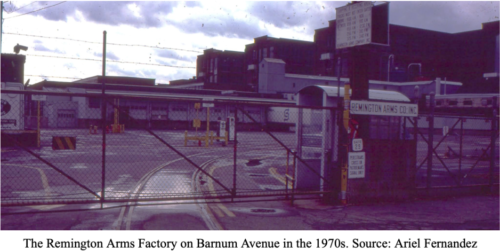

“I still remember the Remington armory in Bridgeport.” In the late 1970s Alex made a friend who worked at Remington Arms “in Bridgeport. That famous factory where they made all the weapons”

“And your friend, was he Puerto Rican, was he Mexican?”

“Mexican” he said “What state?”

“I don’t remember… He was a single man. Well he was alone, but then they [migrants tend to] bring family. Later on he said “Then later he left, I don’t know what happened. I think la migra [the I.N.S.]came and took him. Immigration was all over in those days”. Forging work permits was commonplace, said Alex.

Asked where he met him, he said “I think it was right there [near the factory], because we were going to clean the yards… to clean, to pull weeds. It seems that they [the workers]were on their break and I told him what he was doing there and he told me that they were making rifles and ammunition. I can’t remember his name.”

| “In Connecticut, Mexicans began to appear during the 1940s and 1960s, attached by family ties and work in the factories and mills at the height of these industries.” From “Latinos in a Changing Society” Chap. 3 “The Si Se Puede Newcomers” by Marta Montero-Siebirth (2007) |

The Bridgeport Post reported in 1975 that “Robert D Mooney, assistant district director for investigation said, in reference to the Bridgeport area, “there is a heavy concentration of illegal aliens down there. We find them all along the coastal industrial area from Stamford to New Haven and up to Derby”. But most of those illegal immigrants were not Mexicans. “The illegals come mostly from Caribbean and South American countries. Some of Greek or Polish nationality come to visit relatives and stay for work. And some Chinese illegal immigrants are picked up each year, officials said”.

Meanwhile in Port Chester, by 1974, illegal Mexican migrants found work in J.J. Casone’s bakery. Alex said“Look at Casone’s bakery. At 7am they [the INS]came in, because there were 3 shifts… and they came early in the morning. And everyone was half asleep because they were working all night. The majority were from Michoacán, purely Michoacános worked in Casone’s. Purely Mexicans, from Puebla there were also but more from Michoacán.”

The Port Chester Daily News stated the INS “rounded up 18 illegal Mexicans in Port Chester in December and 13 Mexicans and an Argentine in Larchmont earlier this week” in January 1974. A reporter that year spoke with 7 workers at the bakery, all from Abadiano, Michoacán living on Grace Church St. about their lives. Abadiano is within Jiquilpan municipality, it is 10 mi from Jiquilpan, 15 mi from Quitupan (scroll up for a map of the region).

The next year, in 1975 another 98 people were rounded up, 62 of them were Mexicans. Larger roundups of Mexicans alongside other Latin Americans at that bakery were found in that newspaper later in the 1970s and 80s.

The Mexicans of the American Fabrics Company

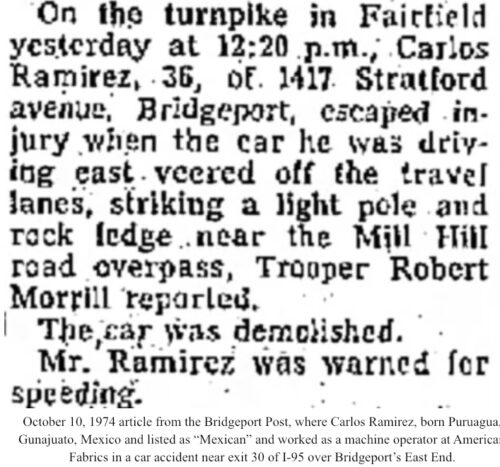

That same year, 1974, in Bridgeport (7 towns to the east of Port Chester), state records show that Mexico City-born Manuel Reyes Filio, born 1930, was already living at 1853 Stratford Ave in the East End and had married Maria in Bridgeport soon after. Also living in the East End by 1974 was Carlos Ramirez-Ramirez at 1417 Stratford Ave along with his wife Lilia Ramirez. Social security claim index records stated he was born in Puruagua, Guanajuato in 1938. By 1984 he lived at 301 Arctic St on the East Side.

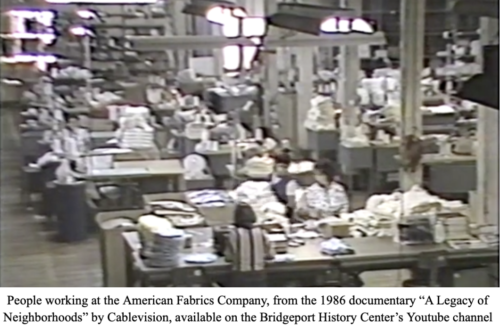

Guillermo Mora, born 1955 in Mexico City, was in Connecticut since at least 1976, and married Gloria Beltran in Bridgeport in 1980. Born 1940, Manuel Valentin lived in Bridgeport by 1982, where he married Julia Vargas. His birthplace was listed simply as “Mexico”. These men worked at the American Fabrics Company, a textile factory on Connecticut Avenue in the city’s East End. Manuel Reyes, Carlos Ramirez and Manuel Valentin were listed as “machine operators” and Guillermo Mora as a “knitter” at American Fabrics on their state death certificates later and on the US Cities Directory Indexes. Guillermo Mora died at age 29 in 1984.

Dr Bassett, a children’s psychiatrist in Bridgeport, said that “My first recollection of Mexicans in Bridgeport, it has to be in the 70s or 80s”. She was in the University of Bridgeport. “You know where there were more, there were more in West Haven. They worked hospital work, and construction, a lot in construction. I know because a lot of them worked with my father” who was a contractor and French-Canadian immigrant from Quebec who settled in Bridgeport. Bassett said in school “most of my classmates spoke Spanish” since there was a large Puerto Rican community, but the few Mexicans she had met then were in West Haven “but they didn’t start off in West Haven” therefore she said that there must have been some in Bridgeport.

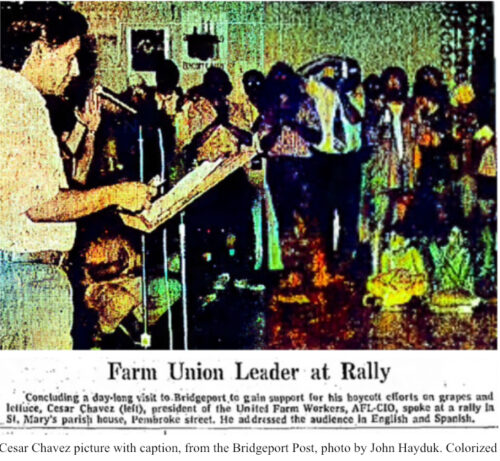

Cesar Chavez Visits Bridgeport:

On the last day of July, 1974, farm workers union organizer and Mexican-American activist Cesar Chavez spoke at a news conference in the University of Bridgeport to garner support for the grape and lettuce boycott and spoke on Gallo Wines illegally hiring illegal migrants and contracts with teamsters to suppress the farmworkers union. He attended a conference at St Ann School where Cesar Batalla, the local Puerto Rican activist, called for the boycott of the grapes and lettuce and said the teamsters agreed to allow for unionization. Chavez joined supporters gathered picketing at a Pathmark on Main Street in the North End (a Price Rite as of 2024) as they sold Delano grapes. He was received at St Mary’s Parish on Pembroke St on the East Side by the local Puerto Rican community, with the Bridgeport Labor Council President, the local priest, and a representative of Mayor Panuzio speaking. Chavez spoke in Spanish and English on the challenges of organizing Puerto Rican tobacco farmworkers in north-central Connecticut.

Scattered Records of Bridgeport’s Small Mexican Population:

In the late 1970s, when Maria Carmona was in highschool, a new Mexican family, the Jassos, moved to Stratford. “that was so exciting…to have MEXICANS right in my hometown. By then, my older brothers were in college, so the Jasso kids were like my “little brothers” until I left for college too in 1981” she said that “My mom and dad became like their sponsors, explaining how things got done in the U.S., etc. Like my dad, Mr. and Mrs. Jasso spoke little English when they arrived, but my dad encouraged them to learn, for their kids’ sake. (My dad came to the U.S. as a full grown adult and spoke no English. He learned as he lived, but eventually took classes at night school after we moved to Stratford.)”. A recession in 1974 hurt Guillermo Carmona. Maria remembers that“when the recession of the 1970s hit, things went south. So he found work at a couple of jobs – bus driver, cleaning a bank – to earn income. Eventually he was hired by General Electric to work at its Corporate Headquarters in Fairfield.” where his wife worked.

By the mid 1970s a Mexican opened a restaurant 3 towns to the south of Bridgeport in Norwalk “The locale was yet-to-be yuppified Washington Street in South Norwalk, Conn. A jolly, rotund woman whom everybody called Mama Vicky had opened a restaurant called Acapulco. Even though she was fresh from her hometown of Matamoros, Mexico, [Izúcar de Matamoros in Puebla, north of Tehuitzingo: see map at beginning] Mama Vicky preferred the resort the name gave her place.” said Connecticut Post writer Charles Walsh in a 1994 guest column for Thomson News Service.

A Bridgeport Post article from June 14, 1977, mentions a “Mexican American association of Greater Bridgeport” along with various other groups as sponsors for the food segment of the International Folk Festival held that year in Fairfield University by the International Institute of Connecticut (as of 2024 the Connecticut Institute for Refugees and Immigrants), the Bridgeport organization providing services to migrants and refugees in Bridgeport. The event was to display different cuisines, dance, song, dress, artisan crafts, traditions, and other forms of cultural display for the different groups participating.

By 1980, the census had counted 322 Mexicans or Mexican-Americans in Bridgeport, up from just 24 in 1970. It was second in Connecticut behind New Haven’s 491 Mexicans. In New Haven, were Chicano students from the southwestern and western United States (Texas, California, New Mexico, Arizona, etc) studying at Yale. MECHA, a Yale Mexican American advocacy organization, was founded there in 1969.

Of the 322 Mexicans counted in Bridgeport, 125 were born in Mexico.

In the entire Bridgeport area (Bridgeport, Fairfield, Stratford, Milford, Trumbull and Shelton), according to the census, there were 171 people born in Mexico, of which 82 of them arrived in the United States between 1975-80, another 44 between 1970-75, another 7 arrived between 1965-70, and the remaining 38 arrived the decades before then.

Mia was a union organizer for the UE (United Electrical Workers) in the 1970s and 1980s. She “worked with many Spanish speakers” from various nations. She recalls “UE represented workers in what was then known as the electrical manufacturing industry. At places like GE and Westinghouse, in addition to Singer sewing machines in Bridgeport… Based upon memory and observation, most of the workers of Mexican heritage in the ’70’s were not recent immigrants (1st and 2nd generation) Many of the other Spanish speaking immigrants were recent immigrants.”

There were only 627 Mexican born people counted in the entire state of Connecticut in 1980.

1982, the Lost Mexican Decade. A Poor Region’s Mass Migration to “Puebla York”:

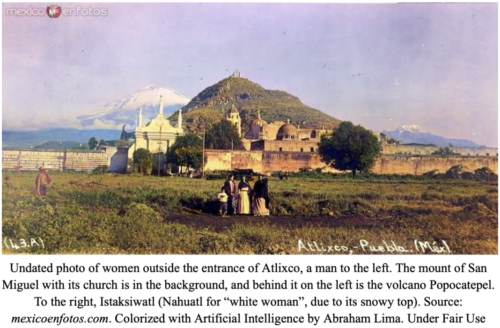

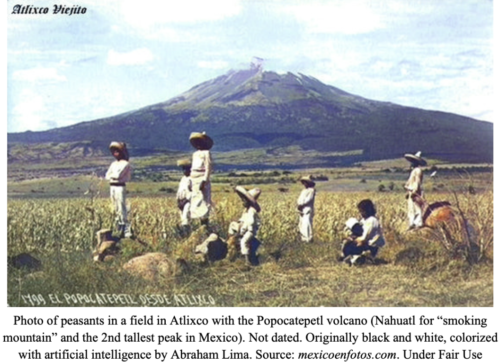

Migration to New York by word of mouth pushed north of Chinantla, Piaxtla, Tehuizingo, or Matamoros towards the Atlixco Valley of Puebla.

One example is the town of Xoyotla, shown here as an example of a place from the Atlixco Valley. Xoyotla is “nearby Atlixco” a city near Puebla City and Cholula. According to “Tres circuitos migratorios Puebla-Estados Unidos”, the people from this town were able to get to New York by the connections with friends from the nearby Atlixco Valley and Ocoyucan municipality who were already in New York City.

“Their native tongue is an Indian dialect called mexicano [another word for Nahuatl]. They speak Spanish with a distante lilt and English hardly at all. Sixty miles north of Piaxtla and dramatically poorer, Zoyotla is just one of the many villages in the state of Puebla that feeds the New York labor market… The flow from Zoyotla began 10 years ago [in 1978]when Luis Vargas, encouraged by friends from a nearby village, arrived in Brooklyn… Today about 200 men and an increasing number of teenage girls from Zoyotla are living in Brooklyn, Queens and northern New Jersey ” reported Newsday in November 1988.

Half of the children born in the town die, the article states. “The village’s tranquil facade belies the malnutrition, illness and desperation of its residents… its Indian peasants rely on rain-fed cultivation of corn, literacy is rare, and about 20 percent of the children don’t attend school because their parents can’t afford it”.

1982 saw the start of Latin America’s Década Perdida, or lost decade. Interest rates went up, much of the world hit a recession in 1981, from the many loans Mexico and Latin American countries took out could no longer be paid back. Oil prices went up, leading to drops in Mexican oil exports. The peso inflated from 20 pesos equaling a US dollar to 70 per dollar in one year. In August, Mexican president Lopez Portillo addressed the legislature and broke into tears, begging forgiveness from Mexico’s poor on camera. The late 1980s saw the explosion of the Mexican population, almost all from the Mixteca (southwestern) region of Puebla in the New York area.

Affected by the crisis and foreign maize were peasants from the Atlixco Valley in Central Puebla near Puebla City (60 miles north of Chinantla and the Mixteca), also subsistence farmers. Since Valley was new to US migration, some farmers used coyotes (smugglers) mainly from the southwest region that guided them to New York City, who then brought more, aiding a migration chain from the central Puebla region to New York, mainly from the Atlixco valley. “I passed a few from Atlixco, a few from San Pedro…now it’s a chain… a chain that cannot be stopped” said one such coyote. The Mexican population in New York City was 21,623 in the 1980 census.

1980 marked the first decade Mexicans became the largest immigrant group in the United States, surpassing Italians. According to a 1985 New York Times article, Italian Americans were the largest ethnic group in Bridgeport, with a large Black and Hispanic (mostly Puerto Rican) population , and a “growing number of Asians and Latin Americans”.

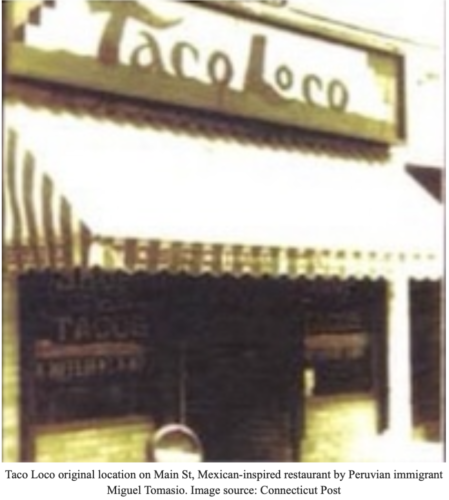

Taco Loco opened as a truck in 1982 on Main Street and Fairfield Ave in downtown Bridgeport and is considered to be the first taco truck in Connecticut. It was opened by a Peruvian (not a Mexican) immigrant, Miguel Tomasio, (among the first Peruvians in Bridgeport). He opened a restaurant with the same name in a three-decker building along Fairfield Avenue in Black Rock in 1989. He told CT Post in a 2012 article on Taco Loco, “Mexican food was not very popular in this area,” Tomasio said. “It didn’t take off for a while and it took us three years to get going.

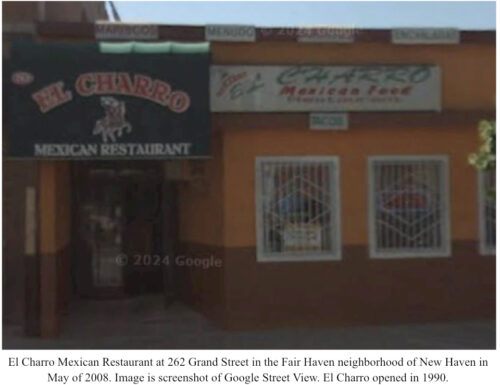

Over in New York City, Mexicans became a vital part in the construction and food/restaurant industry replacing mainly Greeks, Koreans, by then mostly self-employed, as cheap labor. Greek owned-diners sought Mexican workers in the 1990s. Mexican storefronts and food trucks opened.

Mexicans spread outwards from the city into New Jersey. By this time, Poblanos had settled in the former industrial city of Passaic, NJ. Mexicans arrived in the 1960s and 1970s for factory work from New York. Mostly Poblanos. “Passaic is a second Puebla, many immigrants from Piaxtla, Chinantla, and Atlixco live here” said bodega owner Jesus Delago ” to El Diario NY in 2014.

Closer to Bridgeport, Mexicans settled along with Peruvians and Guatamalens in Port Chester, New York, joining the Hispanic population of Cubans who fled Castro in the 1960s and worked in factories.

“I know you lived in Port Chester, but would you happen to know when Mexicans settled in Bridgeport?” Since he didn’t live in Bridgeport then, only passed through it on the way to work in New Haven, he “doesn’t know anything about” the topic. For Port Chester “There were few Mexicans at first, but later they ended up populating the town. They came because there was a lot of work in Port Chester, a lot of factories”. In the 1980s as the factories closed, Latin Americans began to reach critical numbers, arriving for jobs in restaurants and landscaping in wealthy Rye, Mamaroneck and Greenwich.

In terms of Mexicans in Connecticut, Alex said that “In Stamford there are people who arrived in the 80s and before, they have bodegas, businesses. like Don Tomas, who owns bodegas in Bridgeport, New Haven, Norwalk and Stamford”, such as the “Los Luceros” Mexican grocery stores at Cove Rd, Greenwich Ave and Lockwood Ave, in Stamford, Woodward Ave in Norwalk and formally on Grand Ave in New Haven. They’re “from Tehuitzingo, Puebla”.

Further north, “I had friends from Michoacan that lived there” on Ely Ave between Mulvoy St and Lexington Ave in South Norwalk. “They lived all on top of each other. All Michoacanos”. They were single working men who lived together to save rent. “There lived 28 in one apartment” That was in “Like in the 80s, the 90s, yes the nineties… Don Lupe’s uncle lived there; that man had been there [on Ely Ave] since ’75”. When Lima began working for the city of New Haven’s parks and recreation department in 1984, he remembered “there were two brothers. Tomas, his brother Alberto and their mother… from Puebla. They lived on Washington Ave… none of them had papers [legal residency]”. They sold barbacoa [Mexican slow cooked meat in a ditch or earth oven] all over New Haven”. He couldn’t recall anyone from Mexico he knew in Bridgeport at that time.

In Bridgeport there were relatively Mexicans instead. Maria Carmona recalls that “I remember first noticing more Mexicans in Bridgeport/Stratford after I graduated from college and was living in New York. I’d ride the train to Bridgeport and just notice little things…a face, hear someone speaking Spanish with a Mexican accent. That was in the late 80s/early 90s, and the Poblanos had already arrived in big numbers in Manhattan. We used to say that we were “spreading out” into Bridgeport.”

Lillian Cotto, of Puerto Rican and German heritage, born in the late 1930s, has lived in Bridgeport her whole life. “Yes there were quite a few!… Mexicans started coming to Bridgeport in the 1970s. They worked in restaurants, as dishwashers, as waiters… They came to feed their families in Mexico… They spoke good English.”

“Not Many, But Some”. From Puebla York to Bridgeport

In 1986, a then 18-year old Guadalupe (Lupe) Lucero Flores, her siblings and their mother, Gloria Flores Huerta, moved to Bridgeport from The Bronx, New York. They were from Tulcingo de Valle, Puebla, which is 2 municipalities to the west of Chinantla, and one away from Piaxtla, where the first few Poblanos to New York came from.

Lucero, Lupe’s mother, said the family arrived in New York City in 1981 from Tulcingo. Gloria’s siblings, Socorro and Rafaela, were already there. “They worked in a clothing factory” and so did Guadalupe when she arrived. “A friend of my daughter arrived in Connecticut first” and got a job at Pancho Villa Restaurant in Westport. She settled “because she got a better job here.” She invited her daughter Lupe and soon after Gloria and her other children arrived in Bridgeport.

Lupe’s sister-in law, Lizzeth Vivaldo, a representative at the Institute for Refugees and Immigrants on Park Ave, explained that “They moved initially because Lupe got a job at “Pancho Villa Restaurant” located in Westport and the commute was complicated, especially in the winter season.

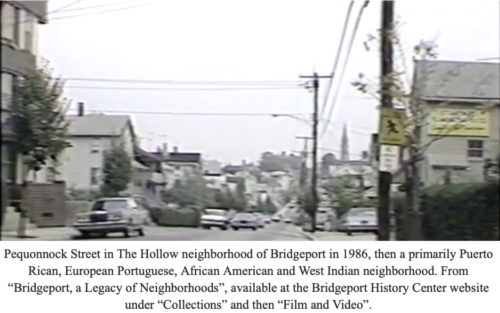

The Lucero-Flores family “looked at Bridgeport as the place where they could live, because the rents were cheaper than NY and more spacious, they liked the tranquil life of the suburbs out of the chaos of the Bronx. Their first residence was in Pequannock St, and they lived mainly in the South End of the city” near the University of Bridgeport.

Gloria said in New York City “There was more immigration there [I.N.S.], they persecuted them [illegal or undocumented immigrants] a lot, they’d even grabbed them on the train. They [the workers]came out running from the factories. They trained us to hide when they came. To hide under our clothes” if the INS were to come into the textile factory where they worked in New York City. “Not so here, on the contrary, here they wanted workers. When immigration arrived at the restaurant they told us” and would be told to hide, “they also punished the owners. The owners didn’t want all their workers to be taken away.”

Asked how they got along with other Hispanics “There were a lot of Puerto Ricans here. Well, as we were not problematic, we got along well with all our neighbors. That’s because I always taught my children that no matter if they’re Dominican, Puerto Ricans [she listed other ethnic groups]… [something related to the Virgin Mary but was not heard well]we’re all people.”

As Roman Catholics, as most Mexicans are, they found “not many, but some” Mexican families in town via the Roman Catholic church.“According to Jose Lucero (Lupe’s brother), when they came, there were other Mexican families living already in Bridgeport, Celia Lucero and Cirino Lucero both from La Independencia, Puebla [part of Tecomatlan municipality, right between Tulcingo municipality and the municipalities of Chinantla and Piaxtla], who lived in Washington Ave., and worked in a restaurant “Onion Alley” in Westport, and there was a woman from Chihuahua and another one from Jalisco, but he doesn’t remember their names.

The job at Pancho Villa was a recommendation from acquaintances, Aristeo Garcia and Rafaela Vallina, from La Independencia, Puebla, and Acaxtlahuacán, Puebla [the town next over from Tulcingo to the west]respectively. They lived in Park Ave. And to their knowledge, these were the only Mexican families living in Bridgeport at that time”.

On other Mexicans in Bridgeport at that time “We didn’t know them. How would we meet them? We always lived with that fear” of getting deported.

There were, in fact, other Mexicans who had arrived in Bridgeport by 1986.

In 1986, that same year, was also the year Rufino Flores settled in Bridgeport. “I came to New York in 1980… to Brooklyn. I’m from Puebla. Atlixco. Well, rather, we are from a town- La Trinidad Tepango.” La Trinidad Tepango is a village, then bordering the city of Atlixco in Puebla. Today it is part of the city itself.

Of La Trinidad Tepango’s 475 households in the Mexican 1980 census, 260 of them had dirt floors, 44 households had cars, 23 had fridges, and 2 had telephones.

La Trinidad Tepango was “well, pure countryside. They planted jicama [a Mexican turnip], maize, onions, tornachiles, all of that was planted. Even today.”

Rufino said when asked about economic conditions “There is no poverty there like… [other places] not very poor because we sowed… there were some few that did have nothing but because they didn’t want to work… it was, like, middle class”.

Rufino Flores said “I was in the D.F. for a long time, I was hardly ever in my town”. El D.F.” is short for the “Distrito Federal”, referring to the federal district of Mexico City.

Asked if many from his town were already in Brooklyn, Rufino Flores said “No, not there either. I came in 1980.” to New York City from Mexico. “I arrived in Brooklyn. I worked in New York for some time” He and fellow Mexicans in New York worked in “Restaurants. Deli restaurants. I worked in all delis. Cleaning dishes. cutting vegetables.” His uncle, Fernando Casiano, had also arrived in New York that year. He arrived on Marcy Ave, Brooklyn.

Casiano went to New York City specifically because the family of the person who brought him across was there. “And as you said, I wouldn’t call her a “pollero” I tell you, the person who helped us get through, well, she was from Atlixco. And she already had a relative here in New York, I think she had one or two relatives. So she would send them, and that relative here would help them find an apartment, find work, and that’s where it all began. I also have a brother in California, but I didn’t stay there, I came here.”

Asking Fernado Casiano why people emigrated from La Trinidad Tepango, he said “well, like everyone else, because of necessity”.

Fernando Casiano said, “Everyone because of necessity, for pleasure no. Nobody comes because they want to”. Asked how poverty was like “well, well that. We only ate once a day”.

In the 1930 census (available on Ancestry.com), most residents in La Trinidad Tepango spoke Nahuatl (also called “Mexicano”). Fernando Casiano speaks Náhuatl “not fluently… it is what my mom spoke with me” . By the time he left in 1980, the language spoken there was “all Spanish”. In the 1980 census, of 2,802 in La Trinidad Tepango, 361 were bilingual in both an indigenous language and Spanish. 30 people spoke an indigenous language only (no Spanish).

In terms of people from Atlixco in Brooklyn then “Eh, few. But there were already a few.” Asked “when the people from Atlixco began to arrive [to New York]?” He said “well if I’m not mistaken, we [Atlixco migrants] came from the Atlixco area around ‘77. Some arrived in ‘77, ‘78, like that. And it may be that they have come here before but I didn’t know them.”

Rufino Flores came to Bridgeport because “He too was invited by a friend. That there was a job here” according to his uncle Fernando Casiano. Rufino Flores said that “No, one always searches. Nobody invited me, I came by myself” from Brooklyn.

He got the idea to head to Bridgeport because “I had a friend here and he said, “Do you want to go to Bridgeport?” and I said nah. There was a lot of work in New York at that time.” In Bridgeport when he arrived “There were a few from my town” of La Trinidad Tepango. “I came in 1986 and I’ve never left”

Asked first impression of Bridgeport, he said “there was good business to get ahead”.

In terms of Mexicans “We’re talking about some 30”. Asked how many Mexicans he knew of when he arrived in Bridgeport that same year. “There were like, that I knew, like only 30 in ’86.”

When he arrived, Rufino said there were “about 5” people from La Trinidad Tepango, Puebla in Bridgeport. Asked if those men had also come recently from New York, “Not the boys [from his town in Bridgeport then], they had come first…”. Flores and the few men from his town who had come before him to Bridgeport were “the first, we were the first.” from La Trinidad Tepango in Bridgeport. They were in Bridgeport “well, the same thing, to look for work. To get ahead”.

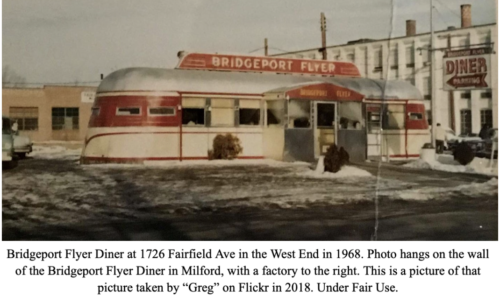

What job did Mexicans have when he arrived in Bridgeport in 1986? Flores said “it has always been restaurants”. Asked if factory jobs or construction “no, never”. The restaurants were “the diners…Greeks… Colony I, Frankie’s Diner”.

Frankie’s Diner was owned then by Petros Roussas, of the island of Andros, Greece and Victor Hasiotis of Katerini, Greece.

Asked when Mexicans began to work in the diner, Nick Roussas, the son of Petros Roussas and current owner of the diner, said, “It’s hard for me to tell. The oldest Mexicans I have working for me is [working at Frankie’s for] 38 years [-around 1986]. Tony… Tony is from Puebla… We were kids with Salvador”

At Frankie’s Diner before Mexicans there were “Greek, Turks, Egyptians, Puerto Ricans… 70s to 80s mostly Puerto Ricans. Mexicans didn’t come until the mid-80s… from the dishwasher to the cook to the chef.” By the time Roussas started working in the diner around age 9, there were already Mexicans working at Frankie’s Diner.

“I am from La Trinidad Tepango”, said Tony, short for Antonio. “The first time I came in 84-83…Well I didn’t get here in Bridgeport. First I arrived in New York, but then I went to work- I already forgot-, over there near Poughkeepsie but more up there… Monticello. I was there for about three years, or four years.”

Asked what life was like in La Trinidad Tepango, “Life was very hard there. It was working all day in the fields, from five in the morning to seven at night.”

“Sometimes without eating” interjected his wife, born in Vila Real, in Tras-Os-Montes region of Portugal, and raised in Bridgeport from age 3.

Tony continued “Without eating. Mhm”. They did eat daily, “yes, we ate beans, halaches. At that time one ate meat, I think, once a month. Almost only vegetables, we cut them in the fields.”

His wife said “The first time I went to Mexico, I didn’t eat.” Tony said “When I first took her there, there was hardly any lettuce. There was lettuce, but it was just a tiny lettuce.”

What brought him to Bridgeport? “Well nothing, we came here to work. Since a brother of mine was here, sent for me. But I lived in New York. In Brooklyn…

Tony’s brother came to Bridgeport “Like in ’85. He hadn’t lived here for very long. I also arrived here, not long after, around 87-86… we came by train” from Brooklyn to Bridgeport.

Tony lived with Fernando Casiano, Rufino’s uncle, when he arrived in the United States, in New York. “Yes, I lived with him… in Brooklyn. Mhm… Don Fernando, yeah.” Don is similar to “Sir.” in Spanish, and is used to show respect.

Tony said that in New York City “they were the first to arrive [from La Trinidad Tepango], Don Fernando. He came around 1980.”

“Before when I arrived you didn’t have to suffer much to cross over. When it lasted three or four days- then you were here already.” As an example, “well, there in San Diego, they had you and they distributed you to where you wanted to go. To California, to the [rest of] the United States. From there they got you the flight, they put you on the plane. Here they also had people at the airport. One would pay them”.

The Mexicans in Bridgeport when he arrived “In restaurants.” His brother “He first came here to work. And he told me that there was work here and if I wanted to come.”

His first job in Bridgeport was “Here [Frankie’s Diner]… From my town there were only two” when he first arrived and started working at Frankie’s Diner”. The others from his town in Bridgeport then “They worked in other diners, restaurants.”

They worked in diners as “It’s the best they could find. Since they didn’t ask for requirements at that time”

Asked where he came to live first in Bridgeport, Tony said “Here on Central Avenue. 1477, I still remember that. There were some buildings there but they already demolished them” He lived there first as “Well there were some friends there [also from La Trinidad Tepango], and we lived like 6” in that apartment when he arrived.

There were also people from Mexico City living there, but “From D.F. they didn’t have much time like 3 or 4 months… It’s just that they arrived and knocked there and since it was apartments they went in and said “we’re looking for an apartment, would you give us a place to live?” I told them” if you want for some time” we’ll give them housing until they get something. Since they were also immigrants like us, one of us.”

“With all of us living there, there were about 6 of us” at 1477 Central Ave. The ones from Mexico City, “There were only 2.”

Another family from Mexico City besides living in Bridgeport then, the two mentioned above is that of Francisco “Frank” Sergio Rodriguez, who would come to be known as “Don Pancho” by other Mexicans later on. He immigrated to the United States in 1968, got a GED and was an electronic technician. He lived in Bridgeport since at least 1983 according to records, on Berkshire Ave in the East Side, near Boston Avenue.

Asked if he knew who was the first person from La Trinidad Tepango in Bridgeport, Tony said “Not really, because when I came here there were already quite a few… Fernando still did not arrive yet. Rufino also arrived later. I think I arrived here first and several others also because there were already some [from La Trinidad Tepango] here working [in Bridgeport].

Tony recalled that in Bridgeport, those from his town, “Well, we didn’t all know each other, like 10 or 15 of us over there, yes. And then, little by little, after that, the whole town starting coming”

Asked what he worked in in Bridgeport, Rufino Flores said “the diners. In Colony Diner I and in Frankie’s Diner”. Rufino Flores worked at Colony Diner first, which is where his friend had gotten him a job.

New Colony Diner I was located in Monroe at 568 Main St (today Monroe). In 1976, Antonios and Fani Loukrezis became the owners of New Colony Diners. They had a summer home in Andros, Greece according to Mrs. Loukrezis’ obituary.

An employee, Stergios Koutikas, came to the United States in 1973 and started a dishwasher at Green Comet and New Colony Diner until he opened New Colony Diner II in Bridgeport at 2321 Main Street near St Vincent’s Hospital.

Nick Roussas, the owner of Frankie’s Diner in 2024, said “Rufino Flores worked here when I was a kid. When I was a kid my family rented the first floor of our house to him and his young family. He was a nice man. He was the nicest man in the world”. He said “the other apartment was rented to other guys”. Asked what state they were from, Rousass said “Puebla”. The Roussas’ family moved to Newtown in 1988.

Nick Roussas on a YouTube podcast called Bridgeport Stories, said his father Petros Rousass in the 1970s “they bought the house on Maplewood Avenue where I grew up. Maplewood and Wood”. Roussas said, “Yes, that house, they [Rufino’s family] rented the first floor.” on 448 Wood Avenue, right on the corner with Maplewood Ave in the West Side. “I was 13-14”.

Rufino Flores recalled that “in the diner there were [people] from all countries, Mexicans and Greeks and Turks, Poles, Hungarians, Russians, Ukrainians. There were a lot of Europeans.”

Asked about Mexicans working in Bridgeport diners, Perry Koutroulas, a Bridgeport- born son of Greek immigrants, said “My dad started working in the diner in 1970. He says there were no Mexicans working there in the 70s. There were some people from El Salvador working there.” This was at the Bridgeport Flyer Diner at 1726 Fairfield Ave in the West End of Bridgeport.

When Mexicans began to arrive, he said “My dad said during the 80s… mid 80s.”. He said instead of being sought out by the owner, the Mexicans that worked there, “They went there looking for jobs” and ended up there.

Antonio’s wife, from Vila Real in the Tras-os-Montes area of Portugal, and raised in Bridgeport since age 3, recalled she first met someone from Mexico in Bridgeport, “oh God. In ‘85, ‘85, yeah ‘85 because I used to work at State Diner…and I met- there were Mexican people working there, Salvadoran people working there. Yeah so about that time…State Diner is on State Street and Iranistan in Bridgeport… That was the first Mexican I met, it was there. Mexican women worked there, Salvadorans worked there, Greeks worked there, Dominicans worked there, Dominican women, more accurately.” New State Diner was located at 926 State Street near Iranistan Ave in the West Side.

She said “When I started working there wasn’t a Mexican. There were Italians, Portuguese, here and there a Brazilian, and many Puerto Ricans because I worked with many Puerto Rican men and women.”

How did the first Mexican get a job at New State Diner? “I have no clue. I guess he went in and asked for a job…

The immigrants when they came in, they were very good to them. They were loved, it was like here too [at Frankie’s Diner]. They weren’t bad, they didn’t treat you bad. They were good. Not just saying that because I work here, I never saw them being bad, on the contrary, the man who had the diner before is no longer here, he died… he was one of them, Mr. Pedro, Nicky’s father, but Victor too. He helped a lot of immigrants, Mexicans here, to get their papers. When the President passed the order that if you had been here for more than five years, and you could prove that you worked and that you had a bill with your name on it, he [Victor] would help you. He would give you a letter to help you find” legal residency in the United States.

The Immigration and Control Act of 1986 was passed by Congress and signed by President Ronald Reagan. The law, among other things, established an 18-month period for all illegal immigrants in the United States who could prove they lived in the US before January 1, 1982.

Asked if when the 1986 amnesty occurred, if there were already Mexicans at Frankie’s Diner, Tony and his wife yelled in unison, “Si! [pause] Siii! [laugh]. You saw that?[more laughter]”.

When Reagan passed the law, the man [Victor Hasiotis] told them, “Guys, we’re going to do this. I’ll help you. You’re going to do this, and I’ll help you.” He helped those who were here [Frankie’s Diner] find letters.”

When Flores arrived in Bridgeport, he remembers there were “some few from my town [La Trinidad Tepango], from the D.F like another five that I knew”. “

Asked where the 30 or so Mexicans he knew in Bridgeport when he arrived were from, Runifo Flores recalled that “I almost never asked them. I just knew they came to work. I’d see them in the diner.” There was “another one from Michoacan, from Oaxaca. But most of us were from Puebla.”

Most Michoacanos in Bridgeport are from the towns near where Mr Valencia was from and who had settled in New Rochelle and Port Chester. The area is around the towns of Cotija, Sahuayo, Jiquilpan, and across the Michoacán state line into the state of Jalisco, in the town of Quitupan.

In terms of people from Oaxaca, one town in Oaxaca saw a wave of people to Bridgeport around the time when Rufino Flores and Gloria Lucero arrived.

Nick Roussas recalled that in the mid 1980s, the states of origin for Mexicans working at Frankie’s Diner, “Puebla and Oaxaca were the two main states”

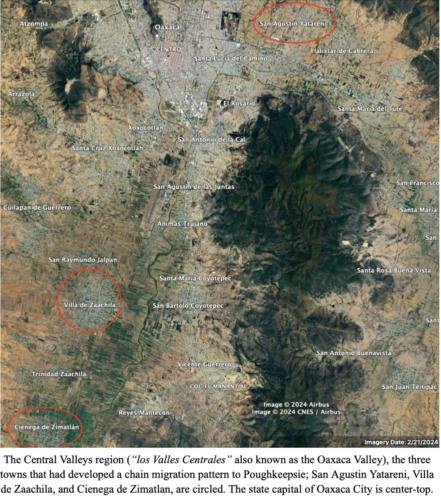

From Zaachila and “Oaxakeepsie”: A Oaxacan Community in New England

Miguel Angel Mendoza, today a painter in New Haven, is from Zaachila and arrived in Bridgeport in 1988. Asked“Would you know why there are so many Zaachileños here? [people from the town of Villa de Zaachila, Oaxaca]. And what brought them to Bridgeport specifically? Was it because of family, was it for a job?”

Mendoza responded “The people from Zaachilla first began to arrive in Poughkeepsie”.

The story the migrants tell says that around 1985, the owner of Athena Diner, which was a Greek-owned diner in Southport, was in Poughkeepsie to visit family who also had a diner.

“The people from Zaachila first came to Poughkeepsie. They say that the owner of the Athena Diner traveled to Poughkeepsie to visit his family who also had or owned a diner. He was surprised by the way the workers did their work, and he asked his relative to get him people to bring to work at his restaurant and he agreed. I don’t know if he gave him some of his workers or looked for workers for him and he brought them himself. Apparently they lived in the restaurant. Then they got them an apartment in Bridgeport and sent them a taxi to pick them up and return them after they had completed their work schedule. The people he brought were like 4 and from there those 4 brought more and in 1988 when I arrived we were only like 15 people from Zaachila and I came because my father was working here too.”

He continued “The first people who came to Athena Diner were around 1985 or so, I don’t have exact information, and all of us from my town [in Bridgeport]knew each other because it was a very small population, barely 10 people, and there were people from Puebla but also in small numbers, very few from Ecuador, Salvadorans, perhaps from some other countries but not so many.”

Villa de Zaachila, Oaxaca today is a city of 30,000, south of Oaxaca City, the state capital. Zaachilla was the capital of the Zapotec Empire, with a Mixtec alliance they repelled the first Aztec invasion. Later, Zaachila and the Zapotec Empire became an Aztec tributary state and the emperor married an Aztec princess. Their child, the last Zapotec emperor, converted to Catholicism in 1521 under the Spanish. In the 1980 Mexican census, Zaachila was a city of 9,654 people.

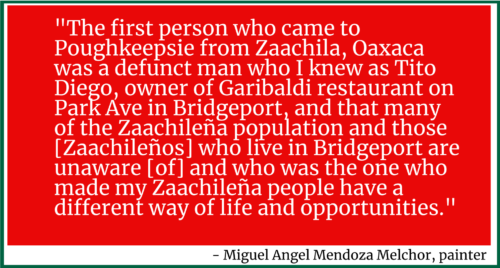

When he arrived in 1988 from Zaachila to Bridgeport where his father was by then, “we were about 15 Zaachileños, and I came because my father was working here too... the first person who came to Poughkeepsie from Zaachila, Oaxaca was a defunct man who I knew as Tito Diego, owner of Garibaldi restaurant on Park Ave in Bridgeport, and that many of the Zaachileña population and those [Zaachileños] who live in Bridgeport are unaware [of] and who was the one who made my Zaachileña people have a different way of life and opportunities.”

Athena Diner opened at 3350 in Southport, CT (a section of Fairfield) in 1975 by John Perthesis. He and his family are from Andros in Greece and also ran Andros Diner in Bridgeport near the Fairfield border. One Greek-American from Bridgeport recalled“The owners of Athena Diner, the wife, her brother lives up there in Poughkeepsie. In fact, he has a diner there.”

For better details, Mendoza said “Ask Everaldo from El Mexicanito”, a store on Park Avenue.

Evaraldo Garica when asked, said that “the Zaachilenos began to arrive here, they began to arrive here in Bridgeport in ’88, ’89, and they [owners of Athena Diner] gave them work. Because the Zaachileños and everyone went to Poughkeepsie, an owner of a restaurant there bought [a diner]here at Exit 19… before it was Athena Diner. So he came, they bought that restaurant, and people were brought there from Poughkeepsie, they were brought to live here. The first Zaachileños brought over to work at Athena Diner, he said that “from Poughkeepsie, the one who bought it [the diner] brought people, I can tell you and assure you that – in fact it was a family, it was a family with a last name uhh, Cuache-Mendoza.”

The migration chain to from the Central Valleys region of Oaxaca to Poughkeepsie, New York started when a young Zapotec, Santiago Adolfo from the town of San Agustín Yatareni in the Four Central Valleys region of Oaxaca (described as a place “where workers earned $6 to $20 a day” – NY Times) in 1980 arrived in New York City. After a few years, he moved upstate to Poughkeepsie. He told his friends throughout the central valley there was work in Poughkeepsie. This created a chain with “increasing immigration from Oaxacan villages- La Cienega, San Agustin Yatareni, and Zaachila” (in the 4 Central Valleys region) according to “New Ethnic Landscapes: Place Making in Urban America.”, which is Chapter 3 of Contemporary Ethnic Geographies in America, by Brian J. Godfrey.

| To most Americans, Poughkeepsie may be a city with a funny name… But to people around Oaxaca it might as well be El Dorado.” “The Poughkeepsie Journal sent a team to Oaxaca to study the community whose presence has transformed Poughkeepsie. They discovered an astonishingly intimate connection. Villagers knew the name of a Poughkeepsie diner” -“Detective’s Kindness Helps Awaken City” – NY Times. |

A different source says the following. “The president of Cienega explained how Poughkeepsie, located 90 minutes north of New York City, became Little Oaxaca. He said that around 1980 three cousins who had emigrated from Oaxaca were working at a New York City restaurant when the owner decided to sell that location and open a new diner in Poughkeepsie. The cousins accepted the owner’s invitation to relocate with him, and the move served as the impetus of the Oaxaca-Poughkeepsie connection” said Tatyana Kleyn in her 2022 book “Living, Learning and Languaging Across Borders”.

Evaraldo Garcia said that “Among the first was Alberto.” referring to Alberto Diego, in terms of people specifically from Villa de Zaachila who settled in Poughkeepsie, where people from nearby towns like La Cienega and San Agustin Yarenti were already settling in the 1980s. “In fact, the one who helped us come here [to the United States], was Alberto.”

According to the Garibaldi restaurant website, “Alberto [Tito] Diego and Luisa Diego… migrated in the early 1980s from Mexico.” His son, who works at Guelaguetza Govery, said “he [Alberto] was young, probably 16”. He had migrated to Poughkeepsie from Oaxaca to support his father. More people from Zaachila began to arrive “by word of mouth, that in the United States there was a- I like to say, a different way of life”.

Everardo Garcia, a relative of Alberto Diego, said “I came in 1988. There I arrived in Poughkeepsie, New York. I arrived here in Bridgeport in ’93”.

“And what brought you to Bridgeport, to the city of Bridgeport?”

Everaldo responded “The business brought me to Bridgeport, we were selling [Mexican products] and here we came to sell, house to house”

Evaraldo’s son, Omar Garcia, born in Bridgeport in 1992, said “My parents arrived in 1990 but in Poughkeepsie…he wanted to open a store but he had friends in Poughkeepsie and didn’t want to compete with them, so he passed by over here and he sold from his car…. he would go to houses to sell, they would tell him “aquí hay paisanos, aquí hay paisanos” [“here are the countrymen”] all the way to Massachusetts”.

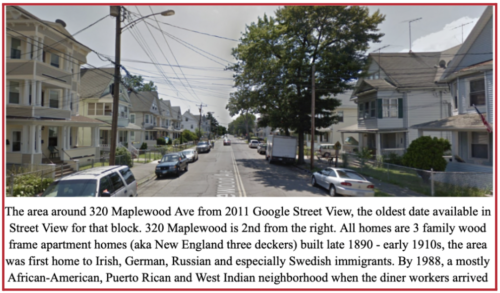

In terms of where Mexicans lived when Everaldo Garcia arrived in Bridgeport. “Ah, most of them lived, there was a house. 320 Maplewood”. This was the address where the first group of Zaachileño workers at Athena Diner resided in Bridgeport after living in the diner itself.

320 Maplewood Avenue is two homes from 448 Wood Avenue. where Rufino Flores and other Mexicans working at Frankie’s Diner were living in.

Asked “What other parts of Bridgeport did Mexicans live in?”

“There was a house near La Poblanita” Bridgeport’s first authentic Mexican restaurant, which opened later, on the intersection with Beechwood and Park Ave not far from Maplewood “That one was full. There were [Mexicans] on Howard Avenue, East Main. That’s where there were most [in those 3 areas].

“What part of East Main?” Garcia said “Oh, almost, almost East Main and Boston Avenue.”

One Oaxacan in Bridgeport who was not from Zaachila in 1985 was Ramona Gonzales Garcia, born 1961 in Huajuapan de Leon, Oaxaca, spent the year 1985 in Bridgeport while attending the University of Bridgeport for one year to learn English. She had previously left Huajuapan to finish university at the Universidad de Las Americas in Cholula, Puebla.

Huajuapan de Leon, near the border with Puebla, is part of the Mixteca Oaxaqueña, part of the Mixteca located in the State of Oaxaca, the region which includes Tulcingo and the rest of the Mixteca Poblana. Romana Gonzales García would serve as the municipal president of Huajuapan de Leon (similar to a mayor in the US) from 2002-2004.

“Maybe 400”: A Colony in Connecticut (late 1980s)

Rufino Flores, asked if around the time he came to Bridgeport, “those from Zaachila were already here”, he said “yes there were, but very reduced”.

Asked how life was like when he arrived in Bridgeport, Rufino Flores said “Everything was better than now. There was more work, everything was better than now… Well before we were very solicited. It was better, you were walking down the street and people would say “it’s the Mexicans! Come over! Put yourselves to work!””.

In terms of education level, Rufino Flores said “What happened is that everyone liked coming over here [to the United States]… Mmm. I don’t know, everyone had primary school [which is up to 6th grade]. When one finishes primary school, one would come over here [the United States].”

Of people aged 15 and older in La Trinidad Tepango, 995 were literate and 431 were illiterate in the 1980 census.

In terms of where Mexican immigrants then assisted mass, Flores said,“San Pedro [St Peter’s on Colorado Avenue in the West End]. Everyone went to San Pedro. The only one where the priest was a Spaniard”.

Around that time, in a 1987 New York Times article titled “For Successful Lace Maker, a Threat” is the earliest mention found by the writer of this article on Mexicans as a group being listed as part of Bridgeport’s ethnic population in a newspaper. It was a story of the Bridgeport-based American Fabrics Company on its success but struggling to afford to stay in the northeastern United States and dealing with a shortage of skilled laborers.

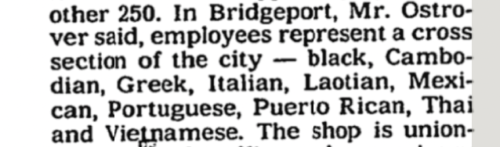

“We have machinery just standing idle,” Mr. Ostrover said. ”We can’t find knitters for these machines.” The company employs 500 to 600 people in its Bridgeport operation and has plants in New Jersey, Rhode Island and Mississippi employing another 250. In Bridgeport, Mr. Ostrover said, “employees represent a cross section of the city – black, Cambodian, Greek, Italian, Laotian, Mexican, Portuguese, Puerto Rican, Thai and Vietnamese. The shop is unionized except for office and supervisory staff,” he said.

The American Fabrics Company on Connecticut Avenue closed its Bridgeport factory and relocated all of its operations to the southern US by 1992. Bridgeport’s deindustrialization was slower, but by the 1980s, Bridgeport saw the closure of factories by companies such as the Jenkins, Hubbell, General Electric, Westinghouse-owned Bryant Electric factories and others.

The Mexican workers at American Fabrics, such as Manuel Reyes Filio, who by then lived at 160 6th St in the East End near the factory, died in 1991. Manuel Valentine, who had his address listed as 206 Park Ave, died in 1992.

Today a painter, New Haven artist Miguel Angel Mendoza recalled his migration experience in a 2022 article by the Arts Council of Greater New Haven. The article stated that:

“Mendoza first came to the U.S. in 1988 to support his family. He was 21. He had planned to teach elementary school math but Villa de Zaachila, the town where he was living with his parents, had other plans. He chose survival. He landed first in Bridgeport, Conn. It was difficult: Mendoza said he experienced the culture shock of American food, education and racism. Back then, he did not speak English. In the grocery store or shopping for clothes, he was treated differently than other customers. “There was a time when I asked someone for help in Spanish, and they pretended they didn’t understand me,” Mendoza said. “They turned around and spoke Spanish to their friends, ignoring me.”

When originally reached out about the origins of the Bridgeport Mexican community, he stated,

“In reality I don’t know about the origins of the [Mexican] population in Bridgeport. I only remember in the year 1988 when I arrived in the country and precisely arrived in Bridgeport, the population was very small…I can’t give you a stat, maybe 400 or less, the majority mostly men and in the 1990s the population grew considerably, there started to be [Mexican] women and later children [in Bridgeport]. The great majority at the time were from Puebla and Oaxaca. Today we find [people] from Guerrero, Michoacan, Veracruz, and other states.”

Told that “according to the 1990 census, there were 599 people of Mexican origin in Bridgeport.”

Mendoza replied that “It is an approximate figure… the census is the most approximate [count]… Many people were afraid to get themselves counted.”

Guadalupe Lucero, her siblings and their mother Gloria, all of Tulcingo del Valle in Puebla, began seeing distant relatives “cousins, aunts and uncles slowly started moving too to Bridgeport from El Bronx, NY and started building a Mexican community” Then later came Gloria’s siblings “and after 4 years of being here they came to live here [in Bridgeport].”

Gloria and her family lived on Pequonnock St, then on Washington Ave. They moved to Cottage St near I-95 and Park Ave by the mid 1990s. One of her various siblings, who all ended up in Bridgeport, settled on “Manhattan St near St. Vincent’s Hospital.”

The Mexican businesses would open in the 1990s “There was also Taco Loco by St Vincent’s [Hospital]. It was a small taqueria, before they moved to Fairfield Ave.”

She said that “They [her relatives]liked it [Bridgeport]. It was calmer, New York had a lot of violence… Well we didn’t know [if there was violence in Bridgeport], we’d just get up, go to work and come back from work at night to sleep. “My children, [she lists the 6 names of her children] would fall asleep on the train, at 3 in the morning” coming back from work in Westport. They “went to the train station waiting until one, two, three o’clock at night because there was no transportation [compared to New York]. Because the train didn’t come every so often, they had to wait until 3 o’clock and from there they walked home at 3 in the morning and nothing ever happened to them thank God.”

Gloria Lucero said that when they arrived “There were no Mexican stores.” Her daughter, Lupe “remembers that there were no Mexican stores at that time, and they had to travel to New York to buy tortillas and Mexican products since it was hard to find in Connecticut.”

After “4-5 years” living in Bridgeport, Gloria said, “I started selling Mexican products by truck here… before there was a store on 160-61st St [in The Bronx] with all Mexican food… I came to sell tortillas [other products]… There was no green chili, green tomato… There was not even maza [instant corn dough]to make tortillas, I sold Mexican products by the truckload.”

Gloria said that “During the week I was going to work at the restaurant. On the weekends we would go buy merchandise in New York”… She did this because there were no Mexican products. “We ate just sandwiches- chicken, turkey… There was no Mexican food. When there were finally Mexican stores [in Bridgeport], I stopped selling.” She sold the products “to my siblings, who were already here.”

The Guerrerense Montaña, Tlaxcalan New Haven, and Casa Grande Supermarket

Gloria Flores Huerta in Bridgeport recalls that when she arrived (~1986), after roughly “4 years in Bridgeport” , she started meeting many more Mexicans in Bridgeport, particularly “from Puebla, Guerrero and Oaxaca”, she’d meet them at church. But when they first arrived in Bridgeport, “No, no, not when we arrived.”

Tony said that later on “well, for other states, more people started arriving – around 89, almost in the nineties, people from Guerrero started arriving.”

The names of the towns “They’re from, like what did he tell me they’re from? Like they’re odd little names that those towns have… some people came from Alpuyecancingo, and others were from – what’s it called… eh.”

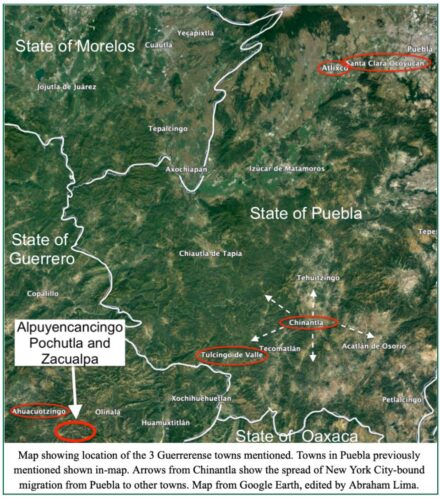

Asking what towns in Guerrero Mexicans in Bridgeport come from, Salvador said, “There are [people from], for example, my town is called Alpuyecancingo. There are some from Pochutla, Guerrero… It is close to my town, Pochutla, and one called Zacualpa, almost also attached to the town. There are many of those here too.”Alpuyencancingo, Pochutla and Zacualpa are located in Ahuacuotzingo municipality in Guerrero’s Montaña region.

Migration from the region to New York City began in the early 1980s, following nearby Poblanos (more depth in next article).

Asked where Mexicans in Bridgeport lived when he arrived, Tony said, “well, the truth is we hardly ever contacted each other. But some people live on Park Avenue, well, various parts. Since we came here to work, we worked at night, we slept during the day, we didn’t go out at all. If we did go out, it was only to buy groceries at the market and that was it.”

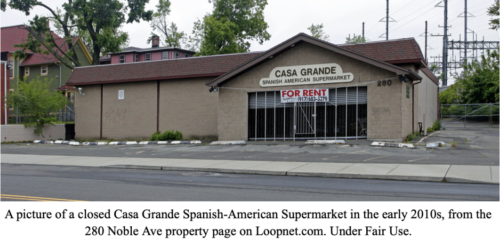

“Oh, they’ve already closed. What’s it called… Casa Grande… We always went shopping there, Casa Grande”

Casa Grande Spanish-American Supermarket was a Puerto Rican grocery store at 280 Noble Avenue on the East Side, just one house away from facing Washington Park. It started around 1976, replacing Noble Supermarket, according to Bridgeport Post articles from that time.

“There were already quite a few [Mexican products], like tornachiles, there were tortillas too. There were beans, canned, but there were already. Not a lot, but they already had most of the Mexican products there. And only that one, because there was no other place”.

Tony’s wife said “Before they opened there [La Poblanita, the first authentic Mexican eatery], there were no Mexican stores at all. The closest thing to Mexican was Casa Grande because it had Mexican products. But just like now, nothing! Nothing!”

How did they get around? Tony said, “oh, by taxi… Some were Hispanic, but most weren’t. And before there were a lot of taxis, not like now.”

For long-distance trips, “when I arrived, it was all trains. Yes, if we wanted to go to New York on a day off, we would go by train. Then we would come back on the train because there were no cars [among the fellow Mexicans]. There were cars, but taxis, and taxis charged more.”

When Tony first arrived, asked how he sent money to his family in La Trinidad Tepango, Puebla and made phone calls to Mexico, he said “Sending money was through Western Union… Stratford Avenue.

To make calls, it was, well, a public telephone. Like before, you’d have telephones on the street” which could make calls to Mexico.

“But beyond that, there was a booth where you could call over there in Mexico. We call it a booth, well. Where you would leave money [to send to relatives in Mexico]they had there so you could call. If you made an appointment, or you called the owner and said I want to talk to so-and-so, to anyone, to my mom or my dad, on such a day, they would let them know and the day would come, you would call, and that was it… Sometimes they had them on the streets, the public telephones. Yes, or if not, they had them in the markets or whatever.” Markets like Casa Grande. “Yes, they also had one.”

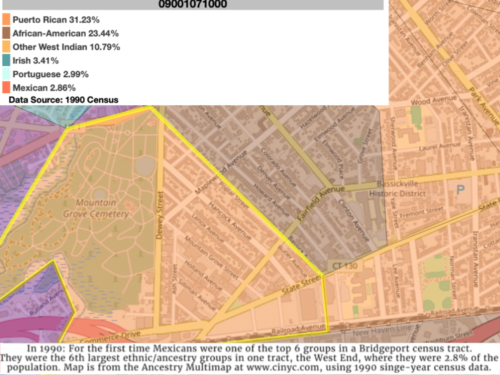

In the late 1980s, there were still no Mexican businesses in Bridgeport.