The Bridgeport Teachers’ Protest of 1915

By Carolyn Ivanoff

Reading a newspaper you can witness the first draft of history from world to local news. In the spring of 1915 the sinking of the Lusitania factored largely in headlines along with the war in Europe. Local and national labor news would also fill the papers. 1915 Bridgeport was full of restless laborers, many of whom were immigrants, who flooded the city and were working in a multitude of industries especially the crucial munitions industry. In the spring of 1915 a teachers’ protest against an unjust merit system splashed across the pages of Bridgeport newspapers along with national and world news. As spring melted into summer and the city heated up, the long hot days of summer would bring over fifty strikes to Bridgeport and 1915 would become Bridgeport’s striking summer. Ultimately by summer’s end labor actions, especially the labor involvement of women workers, would remake Bridgeport into an eight-hour a day town. Preceding the labor strikes of summer, as the school year came to a close, city teachers would engage in a public protest with the Superintendent and Board of Education that would play out in the headlines as the city tried to impose upon teachers a four point merit system.

One of the fascinating side stories of women playing a role in Bridgeport’s striking summer of 1915 began with a small article that appeared at the bottom of the front page of the Bridgeport Evening Farmer on Thursday, May 20, 1915. City teachers, the vast majority of whom were women, began protesting a four point merit system that denied many teachers their pay increases. The Board of Education and Superintendent tried to implement this merit system seemingly without warning. The Board and superintendent probably believed that the women who led the Bridgeport Teachers’ Association would allow them to do whatever they wished without complaint. The Bridgeport Board of Education still features prominently in print and the news on any given day. It seems coverage has never ceased and the issues simply revolve. One hundred years later in 2015 readers may recall the State of Connecticut was in the midst of developing a four point evaluation program for all teachers with an emphasis on test scores. The State system was to be followed by all districts with outcomes (test scores) factoring into teacher evaluations with a greater percentage than teaching practices. Every district was mandated to revise their teacher evaluation systems to conform to this four point evaluation for all teachers.

Bridgeport teachers had organized into an association in 1911. In 1915 they were led by five maiden ladies, President, Mary F. Mallon; Recording Secretary, Bertha Wheeler; Corresponding Secretary, Ada Hallock; Financial Secretary, Mary McNamara, Treasurer, Henrietta Wyrtzen. In 1915 Bridgeport had 28 school buildings plus the high school. Single women were the majority of the teaching and administrative staff. A few men served as principals and several men taught at the high school. The 1915 teachers’ protest against the four point merit system would usher in the Bridgeport’s striking summer and would give the city its first taste of the power of women’s labor. All through the end of May and June articles flew through the newspapers.

Bridgeport in 1915 was a city bursting at its seams. Massive industrial growth, especially the munitions industry, was fueled by and attracted immigration from overseas and all over the nation. By 1920 (the census year), 32.4 percent of the population was foreign born with another 40.4 percent being the children of immigrants. As for the labor force, 73 percent were foreign born. Immigrants came from all over the world seeking religious freedom, better economic conditions, education for their children, and a better way of life.

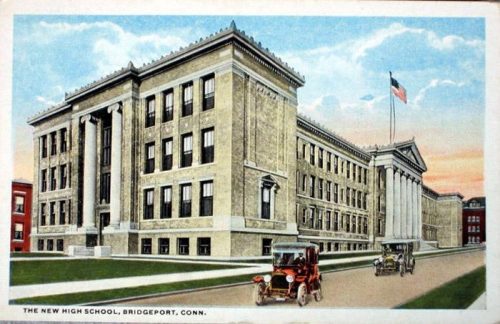

Schools are a microcosm of society and Bridgeport schools were feeling all the stressors of a city bulging with an explosion in population and immigration. The first Bridgeport High School was constructed in 1881  between Congress and Arch streets. This modern edifice on its hilltop location according to newspaper accounts of the time was “far removed from all noise, dust, or odors arising from factories, stables, or the like” The high school building demonstrated a progressive commitment toward education. The brick building had fourteen classrooms in addition to a chemistry laboratory, library, office and reception room. This high school, like so much of the city, had grown too small. Bridgeport’s progressive Republican mayor, Clifford Wilson, and a Board of Education led by President Elmer H. Havens, pledged that not more than 42 students was the ideal classroom size. In 1915 construction on a new high school was underway and would open as the new Bridgeport High School on Lyon Terrace in 1916. (That former “new” high school now serves as Bridgeport’s current city hall.)

between Congress and Arch streets. This modern edifice on its hilltop location according to newspaper accounts of the time was “far removed from all noise, dust, or odors arising from factories, stables, or the like” The high school building demonstrated a progressive commitment toward education. The brick building had fourteen classrooms in addition to a chemistry laboratory, library, office and reception room. This high school, like so much of the city, had grown too small. Bridgeport’s progressive Republican mayor, Clifford Wilson, and a Board of Education led by President Elmer H. Havens, pledged that not more than 42 students was the ideal classroom size. In 1915 construction on a new high school was underway and would open as the new Bridgeport High School on Lyon Terrace in 1916. (That former “new” high school now serves as Bridgeport’s current city hall.)

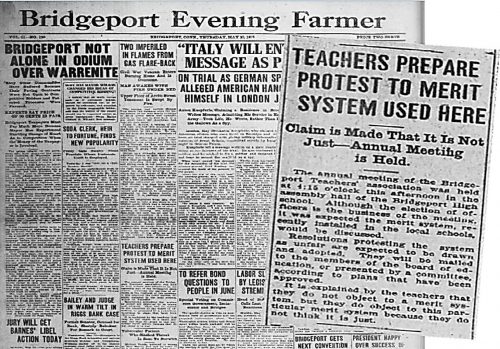

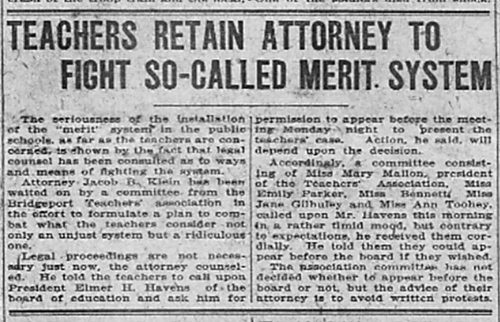

On May 22, 1915 at the bottom of the front page of the Bridgeport Evening Farmer a small article appeared: “Teachers Prepare Protest to Merit System.” Teachers were not against a merit system but they felt this merit system was unjust. A subsequent article the next day reported that a teachers’ committee called upon Mr. Havens, President of the Board of Education, “in a rather timid mood” but he received them cordially and told them they could appear before the Board if they wished. Teachers consulted with their attorney whether to appear or not. From the article it appeared the teachers’ and their attorney favored restraint and dialog in dealing with the Board.

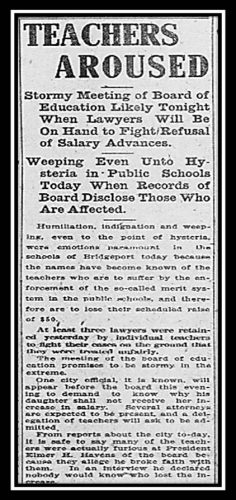

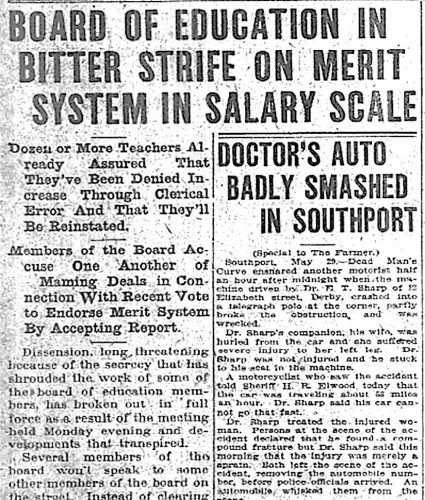

On May 24, 1915 headlines read that Germany declared war on Italy, a dismembered corpse was found at Yellow Mill Pond, and bricklayers walked off the job at Remington Arms for a 10 cent an hour raise from 60 cents to 70 cents. Bricklayers also demanded an 8 hour day, including a change in pay off that didn’t cause them to lose an hour of work standing in the payroll line. Amid this news Bridgeport teachers were no longer approaching the board timidly, they were AROUSED! A stormy meeting of the Board of Education was predicted that evening when the teachers’ lawyers would be on hand to fight the Board’s refusal of scheduled salary advances to those teachers “who are to suffer the enforcement of the so-called merit system and lose their scheduled raises.” “Humiliation, indignation and weeping were emotions

paramount in the schools of Bridgeport today.” In the article one city official tells the press that he will appear before the board to demand to know why his daughter shall not receive her increase in salary. “How can they mark us?” cry the teachers “when some of them don’t visit a room once a year? How do they know what kind of teachers we are?” The paper notes that several of the brightest teachers in the schools were included on the list of those who lost their raises. In one West End school the best teacher in the school failed to show up for work. “Her principal attempted to teach her pupils but she broke down in a flood of weeping… fearing having to flunk one of her best instructors.”

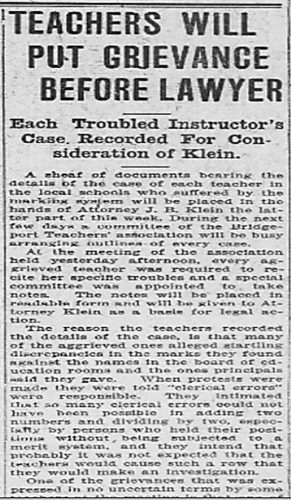

On May 28, twenty-nine teachers went to city hall to find out what marks they received under the merit system. They were rebuffed when the Superintendent Charles W. Dean refused to see them unless they came during office hours. When they did come the next day the teachers posted pickets to insure the superintendent didn’t escape. He was finally located but told the teachers to come again. The teachers wanted to know why the marks their principals “say” they gave them, and the marks the superintendent had denying them their increase of $50 for the next year did not match. Teachers threatened legal action over the discrepancies. One teacher who received a poor mark noted her supervisor never visited her room during the year.

On May 29 amid further war news from Europe, the Board of Education was in conflict among themselves over the merit system. The paper termed it the “so called merit system” in its reporting. The Board told teachers it’s all a clerical error. Teachers found out that the marks that their supervisors and principals gave them were different than the ones the Board had recorded. Teachers marked down with lower scores would not receive their $50 pay raise. Board members also turned on other board members with claims of making deals and keeping other members in the dark. Teachers were again told that the marks received were the result of clerical errors and would be rectified so teachers would have pay raises restored. The article reports that indignation was more and more pronounced every day for teachers who claimed that principals and supervisors had not been in the rooms observing and that the ridiculously low scores were suspect. The paper reported that in one school, despite the claim that the scores were confidential, a student stood up in a classroom and a buzz started. When the teacher asked for order in the classroom, a boy stood up and shouted, “You’re fired!”

On May 29 amid further war news from Europe, the Board of Education was in conflict among themselves over the merit system. The paper termed it the “so called merit system” in its reporting. The Board told teachers it’s all a clerical error. Teachers found out that the marks that their supervisors and principals gave them were different than the ones the Board had recorded. Teachers marked down with lower scores would not receive their $50 pay raise. Board members also turned on other board members with claims of making deals and keeping other members in the dark. Teachers were again told that the marks received were the result of clerical errors and would be rectified so teachers would have pay raises restored. The article reports that indignation was more and more pronounced every day for teachers who claimed that principals and supervisors had not been in the rooms observing and that the ridiculously low scores were suspect. The paper reported that in one school, despite the claim that the scores were confidential, a student stood up in a classroom and a buzz started. When the teacher asked for order in the classroom, a boy stood up and shouted, “You’re fired!”

On June 4, 1915 the Board of Education issued an ultimatum to teachers that they must sign contracts without delay. Previously teaching contracts were signed over the summer and sometimes signed in the fall. On the June 4, fearing legal action by the teachers, the Board tried to force teachers to sign contracts early, with the pay cuts included, thereby negating teachers’ rights to due process. The Board threatened teachers to sign now or be without a job in the fall. “If they don’t sign it will be assumed they don’t want to teach in Bridgeport Public Schools anymore and they will be dropped.” The article also revealed that it was certain that several of the Board of Education members “never heard of the merit system.” One board member claimed that the board had a “clique that doesn’t admit him and several other members to its conferences on Bridgeport school matters.”

On June 5, 1915 teachers announced they would hold an INDIGNATION  meeting. The Teachers’ Association requested every member be present. Teachers were furious that they were being treated unfairly and threatened.Teachers prepared for the Board Meeting on June 14 and had no doubts the Board was trying to intimidate them into accepting pay cuts and the merit system by forcing them to sign contracts early despite the dubious legality of these actions.

meeting. The Teachers’ Association requested every member be present. Teachers were furious that they were being treated unfairly and threatened.Teachers prepared for the Board Meeting on June 14 and had no doubts the Board was trying to intimidate them into accepting pay cuts and the merit system by forcing them to sign contracts early despite the dubious legality of these actions.

Further reporting makes it plain that despite the Board’s attempts to out maneuver the teachers, the teachers had kept good records while protesting the unfair merit marks that denied many of them their increases. Despite the divide and conquer strategy by the Board teachers demonstrated solidarity. When the Board was confronted with teachers’ strong responses they blamed the discrepant merit scores on clerical errors. The teachers responded that so many clerical errors could not have been made by adding two numbers and dividing by two. Reporting showed that the Board clearly thought that the teachers would never question or ask for an investigation, protest, or grieve. One of the things that infuriated the teachers the most was that they had tried to meet with prominent members of the Board but board member attitudes were insufferable. For instance when a teachers’ committee called upon one of the members teachers were forced to wait an intolerable length of time before he would meet with them. The member wore his hat the whole time teachers were present and carried an ill smelling cigar in his mouth. In 1915 this type of behavior from a man meeting with a group of women was shockingly, deliberately belittling and disrespectful.

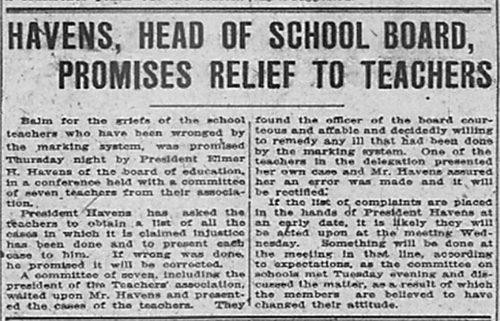

On June 12, 2015, two days before the board meeting scheduled for June 14, the President of the Board, Elmer Havens, met with a teachers’ committee. The news article noted that his behavior toward the committee was courteous. “Balm for the griefs of the school teachers who have been wronged by the marking system was the result of the meeting.” The paper noted that President Havens asked for a list of cases claiming injustice was done and promised, “If wrong was done, it will be corrected.” After the meeting Tuesday and a discussion of the matter it was reported by the paper that the board members “are believed to have changed their attitude.”

So we leave this story of a 1915 labor dispute with the caveat that the Board still had a few tricks up its sleeve. On June 17, 1915 the Bridgeport Evening Farmer reported that the Board would now hold up the contracts of any teacher not living in Bridgeport. Interestingly, two officers of the Bridgeport Teachers’ Association lived out of town. Was this retaliation? The new superintendent also wanted to hire new teachers at a higher salary than was being paid to older teachers at the high school…. And so it went on….

So we leave this story of a 1915 labor dispute with the caveat that the Board still had a few tricks up its sleeve. On June 17, 1915 the Bridgeport Evening Farmer reported that the Board would now hold up the contracts of any teacher not living in Bridgeport. Interestingly, two officers of the Bridgeport Teachers’ Association lived out of town. Was this retaliation? The new superintendent also wanted to hire new teachers at a higher salary than was being paid to older teachers at the high school…. And so it went on….

Jumping ahead to the 1970s, there were more than 50 teacher strikes in Connecticut. In September 1978 Bridgeport teachers voted to strike after months of failed talks between teachers and the city. When the new school year began only 36 of the city’s more than 1,200 teachers appeared for work and the school board was forced to close schools. The strike lasted nineteen days, attracted nationwide attention, and 274 striking teachers were jailed. Union leadership was sent to New Haven Correctional Center and Niantic Correctional Institution to be strip searched and deloused and then taken to Camp Hartell, a National Guard facility in Windsor Locks. They would be joined by busloads of other striking city teachers on a daily basis.

It was the Bridgeport Teachers’ Strike of 1978 that would become the catalyst for the State of Connecticut’s 1979 binding arbitration law mandating a set timeline for both sides to agree during collective bargaining or submit to an arbitrator for settlement. Since 1979, over forty years ago, there has not been a teacher strike in Connecticut. As a former union president, every time we went into negotiations I was thankful that Connecticut had binding arbitration law. Every time negotiations began I remembered gratefully all those teachers, including teachers from my own district in Shelton, who went on strike in the 1970s and sacrificed to make our State a better, fairer place for all educators to collectively bargain.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

The Bridgeport History Center, https://bportlibrary.org/hc/

Bridgeport City Directories for the years 1914, 1915, 1916, Bridgeport History Center

Bridgeport Municipal Reports of the City of Bridgeport for the years 1914, 1915, 1916, Bridgeport History Center

Lambeck, Linda Conner, The Power of Solidarity – Nationwide Teacher Strikes Echo Bridgeport, 1978, Connecticut Post,Sunday, April 22, 2018, front page and page A12

Pehanick, Andrew, Bridgeport (Postcard History Series) May 23, 2005

Van Sickle, James Hixon, Report of the Examination of the School System of Bridgeport, Connecticut, 1913

Library of Congress Chronicling America, Historic American Newspapers, The Bridgeport Evening Farmer, http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn84022472/