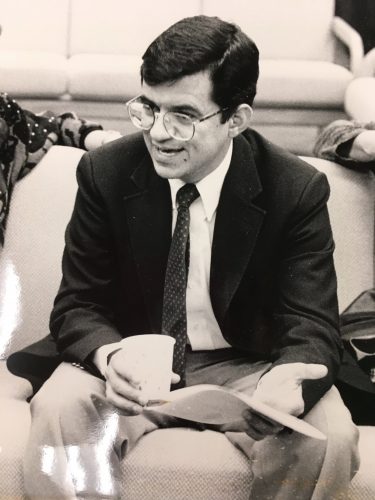

Cesar Batalla

by Professor Sonya Huber, Associate Professor of English, Fairfield University

The life work of an activist can often be portrayed as a bold stance taken at a single defining moment, such as the image of Rosa Parks not giving up her seat on the bus. But like Parks, Cesar Batalla’s activist role in and beyond Bridgeport was not built in a single day; it was a series of daily battles and tenacious monitoring of his community’s needs and aspirations. While leading with this constant action and vigilance, Batalla raised two daughters with his wife and worked in community relations at the Southern Connecticut Gas Company, where he had a huge poster of Che Guevara hanging in his office on the ninth floor.[1]

Batalla moved at eight years old to Bridgeport with his parents from Aguas Buenas, Puerto Rico, the town where his father had served as mayor. At that time he had little idea he would be described with affection as a thorn in that city’s side, or that the Puerto Rican community of Bridgeport and beyond would feel a painful void after he died at age 51. [2] But maybe this was destiny for a man who, as one reporter described him, was given “a first name of kings and a last name that means ‘battle.’”[3] Batalla was placed at age nine in a Bridgeport parochial school with only two minority students. He describes an early awakening when a priest told kids not to visit a nearby construction site or talk to the Black and Puerto Rican workers. Batalla saw the workings of prejudice at this young age, and these experiences gave him fuel for later action.

Batalla attended Bassick High School and then University of Bridgeport but dropped out, was drafted to fight in Vietnam, but then granted leave when his mother’s health failed. At 25, Batalla was already serving as a delegate to the 1970 state NAACP convention. That same year the Young Lords Party formed a chapter in Bridgeport and rented a storefront on East Main Street on the East Side, the fifth YLP branch in the nation. In December of that year, tenants in the buildings and homes surrounding the office went for five days without heat, and the YLP helped the tenants form a renters’ association and stage a rent strike to protest these conditions. By the next spring, conditions on the East Side had reached a crisis point and renters were still withholding their rent to push for repairs.

On May 20, 1971, police came in to try to evict the tenants. A 26-year-old Cesar Batalla stood on the roof, watching as the police came down the street.[4] Wilfredo Matos, the YLP chapter leader, was arrested, and police destroyed the contents of the YLP office. Hundreds of local residents began to pick up stones and hurl them at the police.[5] Batalla later recounted a scene of police with nightsticks grabbing people and beating them. He describes the day as “a rude awakening.” Protestors blockaded a section of East Main Street, and police patrolled with shotguns. The next year, a six-year-old girl died in a fire at one of the neglected properties in the rent strike, and the YLP began a picket at the downtown local mall to urge local business owners to pressure the property owners on East Main Street.

Batalla became deeply engaged in issues of concern to his community and became visible as a direct and clear voice. He was first appointed by the mayor to the Department of Humane Affairs in on Jan. 4, 1972, and he quickly found himself in hot water for speaking his mind. Batalla read a news article about sexually transmitted diseases and then visited various health clinics in Bridgeport, where he found no information about the escalating public health problem. After being quoted in a news story criticizing the city for not providing education about sexually transmitted diseases, Batalla received a public dressing-down, but his comments sparked a new commitment to public health education around this topic as well as the launch of information for high school students.[6] At the end of 1972 Batalla was appointed by the mayor to serve on a commission to study the city’s health services.

One of Batalla’s longest-running commitments was to the Spanish American Coalition (SAC). SAC was originally set up as the coordinating body for the Puerto Rican Youth Organization, the Puerto Rican Parade Committee, and the Spanish American Development Agency (SADA), which was the social action arm of SAC. Batalla was elected SAC chair in 1973 and served on and off in this position for years. [7] SADA ran many programs such as drop-out prevention support for teens and drug addiction prevention and treatment. Batalla was also involved in these years in a Puerto Rican Festival that took place in 1973 and 1974.[8]

In 1976 as just one example, Batalla was involved in a dizzying range of efforts. When elderly people were having trouble with transportation access, Batalla joined the leadership team of an ad-hoc free transportation system called FISH (Friends in Service to Humanity), based on a model started by activists in Western Massachusetts. In 1978 FISH volunteers gave 586 trips, many of them to help people get to healthcare appointments.[9] FISH lasted 13 years as an all-volunteer organization. Batalla also served in 1976 on the Southwest Regional Mental Health Board, spoke at an anti-crime meeting in the West End, introduced a program through Action for Bridgeport Community Development (ABCD) involving block watches, and prodded the city to form an arson squad after a string of suspicious fires.

Batalla first got involved with Action for Bridgeport Community Development (ABCD) when SAC picketed its offices to pressure the group to include Puerto Ricans on its staff.[10] Batalla joined ABCD’s board and became vocal on many issues of concern to ABCD, including the continuing deplorable conditions in schools on the East Side.

[1] http://onlyinbridgeport.com/wordpress/remembering-the-mighty-social-irritant-cesar-batalla-more-than-a-school/

[2] Reginald Johnson, “For a Better Life,” Bridgeport Fairpress, 9/10/87.

[3] Joanna Hernandez Otto, “King Cesar holds court,” Bridgeport Light, Oct. 5, 1988.

[4] Reginald Johnson, “For a Better Life,” Bridgeport Fairpress, 9/10/87.

[5] https://bportlibrary.org/hc/ethnic-history/palante-the-young-lords-in-bridgeport/

[6] Avril Westmoreland, “New Board member wins in VD Information Drive,” No Publication Listed, 3/10/72.

[7] “Batalla re-elected SAC head,” Publication not listed, 5/17/74. “Caesar Batalla Elected New Coalition Chairman,” Publication not listed, 5/18/73.

[8] “Varied Arts Will Reflect Culture of Puerto Rico in Festival at UB,” Bridgeport Post, 9/9/73.

[9] Rose P.B. Venditti, “FISH volunteers hooked on helping.” Bridgeport Telegram, 6/5/79; Rose P.V. Young, “Marchionni Rapped by FISH on Transport for ‘Needy,” Bridgeport Telegram, 10/18/76.

[10] Reginald Johnson, “For a Better Life,” Bridgeport Fairpress, 9/10/87.

AFFIRMATIVE ACTION

Batalla would turn repeatedly to laws regarding equitable hiring as a tool for addressing his community’s struggles. He called out the city in 1975 when it hired only two minority workers out of 54 on a construction job.[11] Batalla was named chair of the Citizen’s Advisory Committee on Contract Compliance, a group tasked by Mayor Seres with creating an affirmative action plan for the city.[12] He celebrated news of a 1976 city affirmative action plan with three-year hiring targets, but then resigned this post in 1977 to protest the committee’s lack of effectiveness.[13] In 1978 he criticized Mayor Mandancini for hiring one Hispanic out of 43 in the city administration. Batalla and other activists also pushed against racially biased entrance exams for city workers.[14] In the same year he was active in the formation of a Puerto Rican workers’ organization with other leaders who had been involved with the YLP including its former leader Wilfredo Matos.[15] The work of Batalla and other activists on joint lawsuits filed by the PRC and the NAACP targeting hiring practices for minorities in the police and fire-fighting forces gained national attention. In 1985 Batalla as president of PRC spoke out against a pay differential in which Spanish-speaking social workers were being hired by the city at a lower rate than other social workers.[16]

[11] John Schwing, “Batalla Raps Lack of Minority Hiring,” No publication listed, 4/11/75.

[12] “Mayor Calls for Action Plan for Minorities in City Jobs,” Bridgeport Post, 10/23/75.

[13] “Fair Employment Papers Signed by Mandanici,” Bridgeport Post, 3/25/76; “Mayor’s hiring record on Hispanics criticized,” Bridgeport Telegram, 1/24/78.

[14] “Group Sees Merit Exam ‘Validation’ As key to Affirmative Action Plan,” Bridgeport Telegram, 12/22/76.

[15] Rose Venditti Young, “Puerto Rican Labor Group Formed,” No publication listed, 11/12/76.

[16] Bill McDonald, “Hispanics slam pay differential,” Bridgeport Post, 1/18/85.

EDUCATION

Battles over funding for teen centers and summer camps provided a flash point between activist groups and the city of Bridgeport for decades, with the city often embroiled in controversies over denying funding to established programs.[17] When Batalla was serving as the vice president of the Spanish American Development Agency, SADA fought to establish teen centers on the West and East Side.[18]

The mid-1970s also marked the beginning of a series of long-running lawsuits against inequities in the Bridgeport and Connecticut school system. Activists argued that the system was in effect illegally segregated. The Puerto Rican Affairs Coalition (PRC), which Batalla also headed, filed suit with the NAACP in 1972 charging that the city wasn’t hiring enough minority teachers; this action resulted in 1980 in a set of hiring quotas for the city created by the U.S. District Court.[19]

The PRC sued the Board of Education and the State Department of Education in 1982 regarding access to bilingual education after a study found that bilingual students were graduating from Bridgeport schools functionally illiterate in both English and Spanish. The suit was settled out of court and resulted in a pilot project at the Elias Howe Elementary School in the West End, with a 67 percent Hispanic population, across the street from Bassick High School. The program was found to be wildly successful by 1987, using a different methodology from standard ESL instruction that began in Spanish and transitioned to English. [20] Years later, in 2001, when Batalla’s daughter Sara Batalla worked in the Bridgeport School system, she testified in Hartford on behalf of bilingual education, and the legislators took time from the hearing to acknowledge her father’s work. [21]

Batalla, as President of the PRC, was in the news again and again over the next two decades commenting when the city failed to meet federal hiring goals for minority teachers, and more rarely praising the city when the targets were met.[22] In the mid-1980s the city developed a plan to recruit new teachers from Puerto Rico, but controversy ensued when teachers arrived and received no assistance in finding housing or transportation, finally turning to the PRC and Batalla for help.[23] Batalla was chair of a collaborative team that won a grant to target the issue of dropout rates of Hispanic youth in 1988.[24] Also in that year, the NAACP and the PRC charged that the state teachers’ test was biased against minority candidates.[25] In 1988 he was appointed co-chair of a task force for implementing results of a mayor’s task force to find ways to keep weapons off school grounds.

Batalla became a member of Bridgeport Child Advocacy Coalition as it was created in 1985 and began to advocate for more special education programs and other services in schools.[26] BCAC was involved in an historic suit filed in 1989, Scheff vs. O’Neill, which charged that Connecticut schools were illegally segregated and that the funding mechanism for schools was unequal. Batalla was co-chair of the coalition that filed the suit, which would linger into the present day.[27]

[17] Bridgeport Post, 10/11/78.

[18] Frederick Fico, “SADA to fight city’s decision,” Bridgeport Telegram, 4/21/78; “City Hall protest airs Puerto Ricans’ plaints,” Bridgeport Post Telegram, no date, 1977; “Bridgeport Latinos protest little say in allocating grant,” No publication listed, 8/14/82: Batalla, as PRC president in 1982, rejected a small grant from the city that was a fraction of what the PRC had asked for to run a summer youth program, instead demanding a greater role for Latinos in planning youth programs to serve the large population in Bridgeport.

[19] Linda Pinto, “Minority leaders faulty school hiring effort,” Bridgeport Post, 5/12/86.

[20] Jon Stokes, “Howe plan touted as model,” Bridgeport Post, 6/5/87.

[21] https://www.cga.ct.gov/2001/eddata/chr/2001ED-00319-R001100-CHR.htm

[22] Linda Pinto, “NAACP feels left out in cold on desegregation meeting.” Bridgeport Telegram, 12/16/87; Linda Pinto, “Schools fall short in minority hiring,” Bridgeport Post, 11/12/85; Linda Pinto, “Minority Teacher hiring is praised.” Bridgeport Post, 8/30/88.

[23] Linda Pinto, “Shocked,” Bridgeport Telegram, 8/11/88.

[24] Linda Pinto, “City Schools get Ford grant,” Bridgeport Telegram, 2/11/88.

[25] Linda Pinto, “Teacher test may be biased.” Bridgeport Telegram, 8/12/1988.

[26] Linda Pinto, “Parents say more special ed programs needed,” Bridgeport Telegram, 3/16/87.

[27] Christopher Blake, “State lawsuit seeks schools’ racial balance,” No publication listed, 4/28/89.

HOUSING

In February 1980, a Latina woman stood outside an apartment building near Bassick High School with a stony expression. In one arm she held a child against her hip. In the other hand she dangled a large dead rat by the tail. She explained to the newspaper reporter who took her picture that she killed the rat by first stunning it with a shoe and then beating it to death with a stick.

This large rat was one problem among thousands in a dilapidated building co-owned by a member of the Bridgeport Chamber of Commerce and a city official. Residents experienced lack of repairs, fires, and loss of heat, and 50 tenants banded together to begin a rent strike.[28] The tenants’ association was supported by the SAC and met at the nearby SADA offices. (The first SADA office had been destroyed by a suspicious fire in 1972 and it then moved around the corner.) After a fire forced the tenants out, Batalla met with city officials, who eventually declared the building “unfit for human habitation,” lacking heat, windows, and water, and residents were relocated.

Batalla did more than talk with power brokers during his years of service to Bridgeport. In this situation he helped to pack residents’ belongings and relocate them repeatedly, and he and other activists asked local restaurant La Gloria to feed the displaced community. [29]

[28] “Weekday picketing by Evergreen tenants,” No publication listed, 2/4/80.

[29] “Weekday picketing by Evergreen tenants,” 2/4/80, photo; Walter Zaborowski, “City finding new homes for 75 in unfit building,” No publication listed, 12/9/80.

BLOCK GRANTS

Batalla became an expert at the use of activist lawsuits to pressure government organizations and expose their weak points. The SAC filed a lawsuit in 1977 against the incursion of community block grants, a then-emerging method for funding social programs that limited the total funds available and did not guarantee ongoing program support. Batalla held the prescient view that these short-term funds didn’t serve the poor or minorities’ needs. He helped to form the Coalition for an Equitable Region, made up of the Spanish American Coalition, Bridgeport NAACP and Bridgeport Area League of Women Voters, and this coalition filed a federal injunction against the grants, then turned the next year to the federal program’s compliance with affirmative action programs, which they knew would be a weak spot, offering a legal challenge. [30] Batalla was then placed on the Citizen’s Advisory Committee on Contract Compliance, marking his rising role as an unofficial resource for Bridgeport; eventually he would serve on the city’s financial review board when it was in danger of bankruptcy in 1988.[31]

[30] Rose P.B. Venditti, Bridgeport Telegram, 4/26/78.

[31] Michael J. Daly and David S. Kassel, “Bucci names banker, activist to financial review board,” Bridgeport Post, 6/10/88.

POLICE BRUTALITY

Echoing today’s headlines, Batalla was vocal beginning in the mid-1970s on the issue of police brutality. Police killed teenager Elizer “Tito” Fernandez was killed in July 1977 on Old Mill Green after a stolen car chase, which sparked demonstrations and demand for an inquiry that eventually led to a federal grand jury investigation connected to larger corruption issues within the Bridgeport police force. [32]

In April 1984 Batalla spoke at the funeral of 15-year-old Carlos Santos, who had been joyriding with friends in a stolen car, which led to a police chase and Santos’ fatal shooting by police. Batalla called for an FBI investigation, not trusting the internal police department investigation, and called on the mayor for action.[33]

“There will be more Carols Santoses and more ‘Tito’ Fernandezes,” Batalla said, “if something is not done.”

Batalla and the SAC attempted to get at the multiple causes of teen delinquency, urging the Governor Ella Grasso to appoint more Hispanics to juvenile justice boards and to DCYS delinquency programs.[34]

[32] “Coalition Plans Protest Today at Police HQ on Youth’s Killing,” No publication listed, 7/9/77; Carol Grabowski, “Hispanic group plans protest on police probe,” Bridgeport Telegram, 7/8/81; “SAC issues statement on cops’ use of weapons,” No publication listed, 6/2/79; https://www.nytimes.com/1981/08/20/nyregion/bridgeport-turns-the-tables-on-fbi-s-undercover-man.html

[33] “Teen buried amid charges of cover-up,” Bridgeport Telegram, 4/20/84.

[34] Rose P.B. Venditti, “Ella Urged to Boost Number of Hispanic Youth Workers,” No publication listed, 1988.

Any of these efforts by themselves would be notable achievements, and yet the list of community issues Batalla engaged on continued. Batalla also served on the board of an organization that raised money for Puerto Rican disabled youth, was chair of the Ford Foundation’s Bridgeport Drop-out Prevention Collaborative, and led the Coalition to Rebuild Bridgeport, which emerged from the Jesse Jackson’s March. [35] He served on the State Commission of Human Rights and Opportunities and was vice-chair of the Bishop’s Commission on Human Rights for the Catholic diocese of Bridgeport. He was active in groups that lobbied for statehood for Puerto Rico, eventually becoming national Vice President of the National Congress for Puerto Rican Rights, which landed him on an FBI list of subversives.[36] He was almost arrested in the mid-80s after he and a small group prepared to disrupt a North End parade during the annual Barnum Festival in order to bring attention to the need for low-income housing.[37] Batalla also went to bat for Cuban refugees with the city, winning a $250,000 grant to relocate 30 Cuban refugees that Bridgeport then refused to accept in 1982. [38]

In 1983 he helped lead Coalition for Justice ’84—including the Bridgeport chapter of the National Organization of Women, Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now (ACORN), and the National Organization of Women and Jobs for Peace—which ran a voter registration drive and brought 2000 new voters into the system from housing projects on the east side.[39] The city voter registration office said activists could not register voters, so Batalla filed suit in Federal District Court. The outcome of the lawsuit included a requirement that the city hire a Spanish speaker for the voter registration office. [40]

Batalla and other activists stayed vigilant on the voting rights issue, and the PRC threatened another federal lawsuit along with the Connecticut ACLU after it was found that voter registrars were aggressively purging voters from the rolls, and that the majority of those voters lived in poorer neighborhoods and were mostly Black and Latino.[41] In 1989 the local NAACP and PRC planned to sue both the local Democratic and Republican parties for voting rights violations in minority neighborhoods. [42]

In mid-1980s, Batalla worked with labor group to attempt to prevent the closing of the Bryant Electric plant and mass firings at Days Inn Hotel.[43] He protested arbitrary work requirements for welfare recipients as well as proposed “English only” legislation for welfare recipients, and he was also active in assessing economic impact when the Bassick Company, central to Bridgeport’s economy for 102 years, closed its local plant and moved operations to Texas in 1988.[44] He and activist Wilfredo Matos tracked the impact that the plant closures had on the Puerto Rican community, which lagged behind other ethnic groups in the city in income and living conditions.[45] While focusing on Bridgeport, Batalla also played a key role in disaster relief abroad, raising money for victims of hurricanes in Nicaragua and Puerto Rico in 1988 and an earthquake in Mexico in 1985. [46] He was also central in the campaign to establish a “sister city” relationship between Bridgeport and Esquipulas in Nicaragua.[47] In 1991 he began work to establish a chapter of a Latino youth leadership group, Aspira, to Bridgeport. He brought 60 high schoolers from Aspira to a Department of Environmental Protection’s Environmental Equity Conference at the University of Hartford to learn about environmental racism in the 1990s.

Electoral politics was always a complex issue for Batalla; he was such a natural leader that people often urged him to run for office, but he was well aware of his power as an outsider and sometimes insider prodding the system. His reputation now is that he was adamantly against running for office, but the clippings file from the Batalla family archive revealed an interview in which he said in 1988 that he had “political ambition” and that he would love to be mayor—though he was not registered as either a Democrat or Republican.

Political office had its dangers, he said, and activists too readily bought into the political machine: “the way the political structure stands now, it doesn’t allow me or a person like myself to get into office without compromising many a thing that I at this point cannot compromise.” In 1989 he resigned from a local board to begin actively exploring a mayoral run.[48] However, he wondered whether the Latino community, then 19 percent of the population, had enough power to land a minority in that office.[49] “We need to work with our people much more and forget about having the machine accept you,” he said.

Batalla was diagnosed with leukemia in 1993, and even as he faced a mortal illness, he came up against the social inequity he had fought all his life. The pool of potential Puerto Rican bone marrow donors was small due to the community’s constrained access to healthcare and suspicion of painful and invasive procedures. Batalla died of leukemia in 1996.

Alma Maya, a Bridgeport community activist who had been born in Batalla’s hometown in Puerto Rico and who was executive director of Aspira, described Batalla as the “glue” that kept the community together, someone who not only knew how to start fires but “to keep them going.”

Cesar Batalla

[35] Rose Venditti Young, “Puerto Rican Tots’ Unit Has New Office Opening,” No publication listed, 2/28/77.

[36] Joanna Otto, “Batalla elected to national post,” No publication listed, 6/1/89; Reginald Johnson, “For a Better Life,” Bridgeport Fairpress, 9/10/87.

[37] Reginald Johnson, “For a Better Life,” Bridgeport Fairpress, 9/10/87.

[38] Paul Guernsey, “Mayor Rejects Funds for Cuban Refuge,” Bridgeport Telegram, 5/12/82.

[39] “PRC considers federal lawsuit against registrars,” Bridgeport Telegram, 7/17/83; Jim Callahan, “No Compromise on deputizing voter registrars,” Bridgeport Telegram, 6/13/84; Jim Callahan, “Puerto Rican leader critical of 2 registrars,” Bridgeport Telegram, 6/14/85.

[40] Paul Bass, New York Times, 2/5/84.

[41] Jim Callahan, “Voting list dispute is settled,” Bridgeport Telegram, 10/12/85; Jim Callahan, “Voter Purge reversed,” Bridgeport Telegram, 9/5/85.

[42] Joanna Hernandez Otto, “Lawsuit planned against parties,” No publication listed, 11/15/89.

[43] Reginald Johnson, “For a Better Life,” Bridgeport Fairpress, 9/10/87.

[44] Vick J. Epstein, “Imports force Bassick to Flee,” Bridgeport Telegram, 5/25/88.

[45] “Depressed: Puerto Rican Group trails other Hispanics,” Bridgeport Post, 5/29/87.

[46] Kenneth Dixon, “Flood news touches many in city, area,” Bridgeport Telegram, 10/8/85; Alan Gottlieb, “Drive to aid Puerto Rico’s flood victims,” Bridgeport Post, 10/9/85; “Hurricane relief fund set up,” No publication listed, 10/3/88.

[47] David Gregorio, “Hispanics are organizing sister city effort,” No publication listed, 8/27/89.

[48] Joanna Hernandez Otto, “Batalla for Mayor?” Bridgeport Light, 2/25/89.

[49] John J. Gilmore, “Block of votes may get traded,” Bridgeport Post-Telegram, 2/20/89.

Information for this article compiled from the Cesar Batalla Personal Papers and Clippings Collection at the Bridgeport History Center. The papers were donated by the Batalla family.